ŌĆŗAt the head of the tunnel, gusts of ventilated air whip outside Phillip BirchŌĆÖs operating booth. Inside, live camera feeds, maps and gauges span out in front of the man at the helm of Metro VancouverŌĆÖs latest effort to withstand a major earthquake and bring water to a growing urban population.

ŌĆ£IŌĆÖm a tunneller,ŌĆØ said Birch. ŌĆ£I've worked underground all my life. IŌĆÖve never done anything else.ŌĆØ

Overhead, 40 metres of sand, silt and clay separate the growing Annacis water supply tunnel from the waters of the Fraser River.

The $450-million project is one of either under construction or in the planning phase across an urban region carved up by rivers and ocean inlets. Last week, construction began on an underground water main under VancouverŌĆÖs ; another tunnel drilled under the Burrard Inlet is near completion.

ŌĆ£WeŌĆÖre getting good speed. We did 12 advances Friday in one shift. ThatŌĆÖs kind of a record here,ŌĆØ Birch said.

Drilling deep underground is not without its risks, but so far the Annacis project ŌĆö scheduled to be completed in 2028 ŌĆö has pushed forward without any major incident, according Murray Gant, Metro VancouverŌĆÖs director of major projects for tunnelling.

ŌĆ£This is the longest marine crossing,ŌĆØ said Gant. ŌĆ£The longer the tunnel, the more chance of things, you know, happening. But so far, so good.ŌĆØ

'Giant manufacturing process under a river'

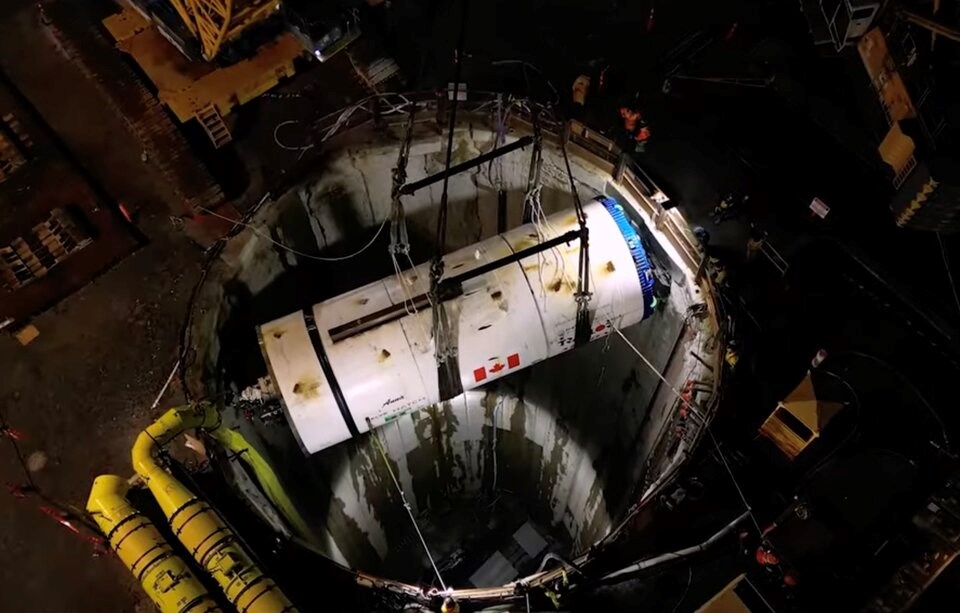

Since 2022, a crew of about 50 contracted workers have accessed the tunnel by descending a 60-metre shaft on the south side of the river.

Workers access the head of the tunnel on rail cars. Drilling 20 hours a day, six days a week, the team has so far pushed the German-built tunnel boring machine, nicknamed Anna, 1.4 kilometres toward New Westminster.

On the surface, automated geo-technical stations constantly monitor ground levels to make sure nothing is collapsing ŌĆö a critical check as the tunnel has already passed under rail lines and SurreyŌĆÖs container terminal. ŌĆŗ

ŌĆŗWhen they reach the other bank of the river, the 2.3-kilometre tunnel will pass between highrises and under SkyTrain lines before reaching the surface near New WestminsterŌĆÖs 11th Street and Royal Avenue.

To drill under the river, crews advance the boring machine several metres a day. With each movement forward, crews fill and cart train cars of excavated clay and mud. Others use heavy machinery to lift sections of pipe ŌĆö manufactured in Nanaimo, sa╣·╝╩┤½├Į ŌĆö into place.

That process is repeated ŌĆ£over and over and again,ŌĆØ said Becky Reeve, a project engineer for contractor Traylor-Aecon who often sits next to Birch troubleshooting alarms and navigating where the tunnel will go next.

ŌĆ£It's just a giant manufacturing process under a river,ŌĆØ she said, sitting on a giant screw at the head of the tunnel.

At 2.6 metres in diameter, the tunnel itself is sealed as itŌĆÖs built, though on two occasions, commercial divers have been sent ahead of the boring machine to check its cutting tools.

On the dry side of the drill, a dizzying array of whirring engines, hydraulics and alarms fill tight walkways.

ŌĆ£We're right under the Fraser River now,ŌĆØ said Birch. ŌĆ£ItŌĆÖs not for everybody.ŌĆØŌĆŗ

Originally from England, Birch has spent 25 years digging tunnels, from coal and zinc mines to hydro power projects. His latest gig before coming to Vancouver was in a Mexican silver mine.

Unlike many of those mine shafts, pipelines like the Annacis water supply tunnel are being built to withstand a one-in-a-10,000-year earthquake ŌĆö equivalent 9 magnitude event ŌĆö while still remaining operational. A published internally by Metro Vancouver in 2022 found such an earthquake could lead to 267 water main failures across the region.

Building a tunnel that solid means boring deeper under the river often into deposits left behind thousands of years ago by retreating glaciers and now submerged under sa╣·╝╩┤½├Į's biggest river.

ŌĆ£If we lost power, all of the water would be coming this way,ŌĆØ said Reeve. ŌĆ£It would really begin to flood.ŌĆØ

That's what the backup generators are for ŌĆö one part of a series of safety redundancies that make the project both very complicated and expensive.

Capital spending to drive up regional utility bills

At nearly half a billion dollars, the tunnel is one of a series of major capital spending projects that are hitting Metro VancouverŌĆÖs budget all at once.

Over the next five years, maintaining clean drinking water to the region is expected to cost $3.5 billion. Another $10.6 billion will be spent to upgrade or build new water treatment facilities.

MetroŌĆÖs operating expenses are also set to rise sharply in coming years, climbing to $2.2 billion in 2029 from $1.2 billion in 2024.

Wastewater plants are being built to handle new federal water quality guidelines while absorbing demand from a population set to climb by one million people by the 2040s.

ŌĆŗSpending has also increased as the regional government has been plagued by high-profile cost overruns. One of the biggest flash points has been the North Shore wastewater treatment plant, a project that has seen its costs spike to $3.86 billion ŌĆö a five-fold increase of the $780-million estimate in 2017 when the building contract was awarded to Acciona Wastewater Solutions.ŌĆŗ

ŌĆŗMetro Vancouver has since cancelled its contract with the Spanish-owned firm and taken the company to court. At the time, the regional governmentŌĆÖs commissioner and CAO Jerry Dobrovolny Acciona underperformed and consistently failed to deliver the project on time and within budget.

To pay its bills, Metro is looking to borrow money that will eventually be paid back through $5.8 billion in future taxes and $2.8 billion in .

This year, the average household paid $698 for critical utilities. Next year, the same household will pay an average of $875, a 25.3 per cent increase.

Metro trying to control costs of 'must-have' infrastructure

In an interview Tuesday, Metro Vancouver board chair Mike Hurley said the regional body has no choice but to build and replace a vast array of infrastructure ŌĆö critical assets that are either nearing the end of life or aren't up to meeting future demand.

ŌĆ£There's nothing more important than safe drinking water and ensuring that supply is there as people need it,ŌĆØ Hurley said. ŌĆ£It's not a nice-to-have. It's a must-have.ŌĆØ

Hurley said construction of the North ShoreŌĆÖs sewage treatment plant came at a time of significant inflation, something Metro staff has said increased costs across all major infrastructure projects. ŌĆŗŌĆŗ

ŌĆŗWhen asked what Metro Vancouver is doing to avoid similar cost overruns in the future, Hurley said planners are focused on building in ŌĆ£really good contingenciesŌĆØ that will be ŌĆ£getting bigger, for sure.ŌĆØ

ŌĆ£The costs of these projects are just getting bigger and bigger, and we are focused on trying to hold them as tight as we possibly can,ŌĆØ said Hurley, who also serves as mayor for the City of Burnaby.

ŌĆ£We don't like going out and telling people they have to pay more. It's not something that any of us want to do.ŌĆØ

ŌĆŗAt the same time, Hurley said there are things the public can do to help keep costs down. He said the region needs to do a better job at conserving water and avoid putting added pressure on reservoirs during the dry summer months.

And when it comes to municipalities, Hurley said itŌĆÖs time they ramp up efforts to install water meters, which would essentially put a price on water at the tap.

ŌĆ£Water consumption is too great per household, and unfortunately, the best way for people to learn that is when it costs you in the pocketbook,ŌĆØ he said.

With files from Jane Seyd and Graeme Wood