sa╣·╝╩┤½├Į’s federal government failed to properly protect more than two dozen threatened or endangered migratory bird species across the country — including the marbled murrelet, a seabird that nests in the coastal old-growth forests of British Columbia — lawyers argued at a Vancouver, B.C, federal court Wednesday.

The case dates back to April 2022, when the Sierra Club BC and Wilderness Committee sued Environment and Climate Change sa╣·╝╩┤½├Į for what they say was an “unreasonable” interpretation of the .

The two groups sued the federal government after Environment Minister Steven Guilbeault issued a protection order for the habitat of critically endangered migratory birds listed under SARA.

That order, claimed lawyers for the environmental groups, only applies to the seabird’s nests — an unreasonable interpretation of the federal law because logging operations often fail to spot them before it’s too late.

Marbled murrelet nests rise 15 to 50 metres above the ground, often tucked into the thick, mossy branches of old-growth trees. Andhra Azevedo, a lawyer representing Sierra Club BC and the Wilderness Committee, told the court that makes their nests “practically impossible to find.”

“The only way to protect nesting habitat for migratory bird species is to protect the area of the forest where they're likely to nest,” said Sean Nixon, another lawyer representing the two groups.

The face of migratory bird recovery

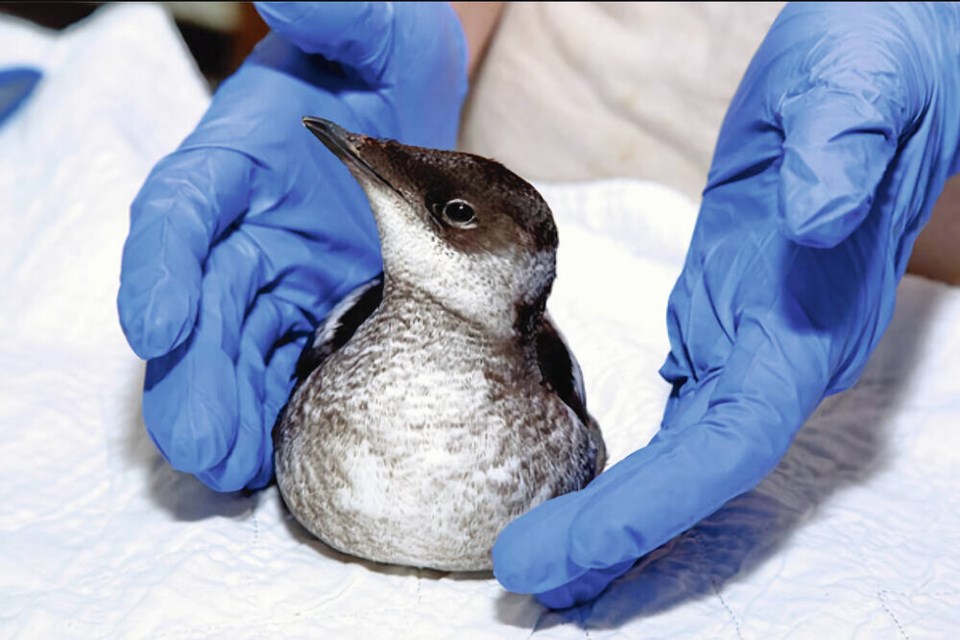

First declared threatened in 1990, marbled murrelets can be found along 4,000 kilometres of North American coastline, though most of the small black and white seabird’s population is found in Alaska and sa╣·╝╩┤½├Į

As few as 357,900 birds are left, including an estimated 99,100 in sa╣·╝╩┤½├Į, where the species has lost an estimated 22 per cent of its habitat over three generations, according to the .

The seabird breeds multiple times throughout its life, and low reproductive rates mean keeping paired birds alive for a long time is key to the health of the species.

The marbled murrelet is threatened by oil contamination, entanglement in gill nets when foraging at sea, and unpredictable ocean temperature swings due to climate change, according to an updated recovery strategy released in 2023.

But a loss of nesting habitat in old-growth forests due to logging remains the “principal threat” facing the marbled murrelet, says COSEWIC.

“Estimates of the total loss of coastal old-growth forest in sa╣·╝╩┤½├Į (much of it likely marbled murrelet nesting habitat) since European settlement, due to logging, agriculture or urbanization, range from 35 per cent to 53 per cent by the late 1990s,” says the latest federal recovery strategy.

The declines continue — in the decade leading to 2011, the province is thought to have lost 5.4 per cent of the bird’s suitable nesting habitat. The federal government aims to limit the decline in the species to 30 per cent of its 2002 population by 2032.

Court action tests laws inherited from the British Empire

The court action represents an escalation of the two environmental groups' efforts to protect critical marbled murrelet habitat. For two years leading up to the request for judicial review, they sent petitions and letters calling on the federal and sa╣·╝╩┤½├Į governments to take action.

When they failed, they turned to federal court, and will call on Justice Paul Crampton to render a decision over the coming months.

The two environmental groups requested the court set aside the minister's decision, declaring the interpretation of SARA too narrow and unlawful. They are also seeking declarations from the court saying the law requires the minister to apply protection orders to migratory bird habitat beyond their nests, and in the case of the marbled murrelet, immediately recommend the protection of its habitat.

Unlike some species at risk, which fall more heavily under provincial jurisdiction, the lawyers are partly leaning on sa╣·╝╩┤½├Į's responsibilities under “empire treaty provisions” — old laws on the books before sa╣·╝╩┤½├Į gained its full independence from the British Empire, according to Nixon.

“In 1916, the United States and Britain got together because birds were being slaughtered indiscriminately,” said Nixon.

Two years earlier, Martha died in a Cincinnati zoo as the last passenger pigeon, a species that as the most abundant land bird in North America, once totalled between three to five billion individuals. At the time, the demand from milliners and restaurateurs was driving the steep decline in bird populations.

When the was passed, it marked the “first international agreement forged to protect wild birds, and among the first to protect any wildlife species,” the federal government noted on the convention's 100th anniversary.

“The [Canadian] government has always been pretty hands-off about that power… they want to interpret it as narrow as possible,” said Nixon.

How those old provisions square with the more modern and Species at Risk legislation remains an open question.

The court’s decision will impact 25 bird species, 23 of which are declining due to a loss of habitat.

Of those, 10 are threatened and 15 that are endangered. They include: three warblers, two woodpeckers, two piping plovers, the Bicknell’s thrush, the coastal vesper sparrow, the horned grebe, the roseate tern, the Williamson’s sapsucker, yellow-breasted chat, and the eastern whip-poor-will.

“This case has a broader impact than that one species,” Azevedo told the justice.

Lawyers for the federal Department of Justice are scheduled to make their submissions on Thursday.

Of sa╣·╝╩┤½├Į’s 373 endangered species, 160 are found in sa╣·╝╩┤½├Į — giving it the highest count of any province.