On day one, I open my eyes to a dark room, no idea the virus had already gone to work.

Outside, the sun is still below the ridge and a thick blanket of icy snow covers the valley. Next to me, the cabin’s wood stove has died out on one of the coldest days of the year.

Too cold to stay under the blankets, I jump out of bed, throwing on a jacket, a down vest, anything to shake the chills crawling up my spine. A quick step outside to grab an armful of split fir and cedar kindling, a dash inside to build a fire.

Add a headache to the chills.

Back in bed, I can’t stop shaking. Over the next few hours, my muscles would seize up as if someone had snapped shut a vise on my lower back.

I put on a mask. I try to sleep it off. “A cold? A flu?” I think. “There’s no way it could be COVID. I’ve been so careful.”

On the ferry, back to the city. That night I wake drenched in my own sweat. By the morning of the second day, Advil finally breaks the fever. I drag myself to the car and across Vancouver, past all of the closed drive-thru testing sites, shut because of the cold to the University of British Columbia’s Life Sciences Building.

From the UBC foyer, health workers are handing out rapid antigen tests.

I focus on standing on the X taped on the floor and saying the right combination of symptoms. Halfway through my list, the nurse tells me to stop, hands me a test kit and tells me to leave (I’d be back an hour later after realizing the one she’d given me was defective).

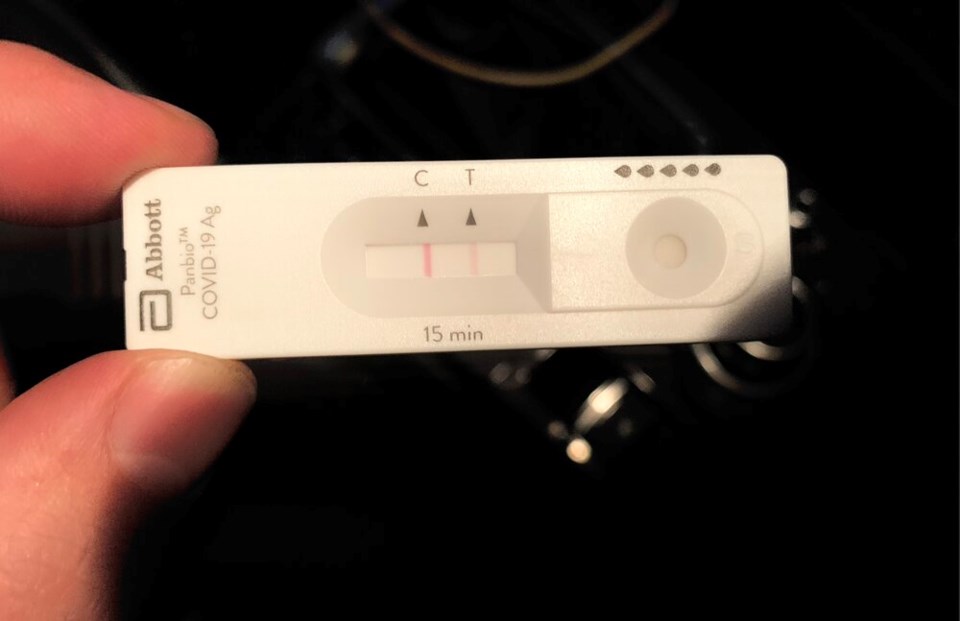

A double swab to the back of the nasal cavity and a thin red line 15 minutes later tell me everything I needed to know: positive, isolate.

“Do not go to work, school, or to any public places for seven days from when your symptoms began…” starts a list of instructions from Vancouver Coastal Health.

A list of seven key COVID-19 symptoms follows. Yet so many of the symptoms I’d come to associate with the disease remained absent. There was no cough, no shortness of breath or difficulty breathing. I had no sore throat, and no signs of nausea, vomiting and diarrhea.

Could the Omicron strain be different?

Less severe?

I have no definitive evidence that I was infected by the Omicron strain. In fact, I can’t even be 100 per cent sure I have COVID-19 after an overwhelmed testing capacity in this province meant I had to get a rapid antigen test, also known as a RAT (the rapid tests give false negatives one out of 10 times and false positives one in 200 tests).

What I do know is two other family members in my household tested positive using a RAT; my nine-year-old daughter, miraculously, tested negative.

Over the next week, we’d all suffer varying levels of aches, pains and chills. My wife would lose her sense of smell and taste, something that is still largely gone. It's a symptom reported less often with Omicron.

At an individual level, there are positive signs Omicron does not lead to as often as Delta or the original strain of the virus.

“The fact that it’s not replicating in the lungs is consistent with what we’ve been seeing with Omicron,” says Sally Otto, an infectious disease researcher at UBC. “It’s really quite different, more sniffles, coughs, more aches and pains.”

Otto points to a pre-print study out of Norway that tracked over 80 people who fell ill with Omicron at a company Christmas party. The most common symptoms, found the study, included a cough, congestion, fatigue and a sore throat. Headaches, muscle pain and fever were also found in more than half of those infected.

“There’s much less oxygen, much less intubation,” says Otto, referring to patients admitted to the intensive care unit.

Still, some modellers have warned the sheer number of cases could overwhelm hospitals this month. Even if you are statistically less likely to suffer severe health outcomes from Omicron, the speed at which it’s spreading means hospitalizations are still climbing. Over the past week, hospitalizations in sa╣·╝╩┤½├Į have already grown over 50 per cent.

There are still many unknowns. On Tuesday, provincial health officer Dr. Bonnie Henry said the province was looking to analyze the “small increase” in hospitalization to understand how COVID-19 is impacting the health system.

But it’s not just life-threatening symptoms that affect people’s lives. Long-COVID has been regularly documented in a significant portion of the population across multiple jurisdictions, including the , and the U.S.

A 2021 study out of found a quarter of healthy health-care workers who contracted a mild case of COVID-19 had at least one moderate to severe symptom lasting for at least two months; another 15 per cent reported at least one moderate to severe symptom lasting for at least eight months.

In sa╣·╝╩┤½├Į, a network of four post-COVID-19 recovery clinics warns those infected with COVID-19 might suffer from long-term brain fog, breathlessness, fatigue and pacing, hair loss, headaches, ringing in the ears, and a loss of taste and smell. Other long-COVID symptoms include feeling exhausted after a minimal amount of activity and a spectrum of mental health problems.

Things get weird

For me, things got weird on day three, when I woke up to swollen gums. (Did I floss too hard?)

In the space of hours, the swelling moved into my entire mouth and tongue, triggering pain every time I tried to chew, swallow or talk.

Don’t confuse “COVID tongue” with macroglossia, when a massively engorged appendage hangs past the chin after too much time on an .

As the pandemic progresses, reports of ‘COVID tongue’ have included signs of discolouration, swelling, mouth ulcers, lesions and patchy tongues.

This month, a group of researchers compiled evidence from . In dozens of cases, they found necrotic ulcers, dry mouth, gingivitis and even the reactivation of oral herpes in patients between age four and 83.

“Every time I swallow it feels like my throat is ripping open,” wrote one Reddit user on a COVID-19 forum.

“I am absolutely miserable,” wrote another.

Researchers understand that the COVID-19 virus often targets ACE2 cell receptors found in the lungs. But ACE2 are also found in abundance in the mouth and tongue, and many think this fact, along with an exaggerated immune response against COVID-19, may trigger symptoms in the mouth.

Some studies have linked oral COVID-19 symptoms to weakened immune systems, while others have suggested it could be “rooted in a complex relationship between COVID-19 and the microbiome.” Nobody knows for sure.

“First-hand observations are often how we understand these things,” says Otto.

As testing falls behind and COVID-19 infections spike like never before, the province now says 80 per cent of all positive cases are Omicron.

So, questions Otto, “Has what we should be looking for changed?”

It's too early to say with any certainty — Otto and other doctors say there’s just not enough data.

Now on day 10, my mouth remains swollen and painful. But it could be worse. At least I’m vaccinated; at least I’m not in hospital; at least I’ll get a little more protection from whatever comes next.

As Henry put it this week, "I’m thankful this strain has arisen now and not earlier on...”

“If we did not have the protection from vaccination that we have in such a large part of the population, we’d be in very, very challenging situations.”

CORRECTION: A previous version of this story stated rapid antigen tests can produce false positives every one in 10 tests. In fact, false negatives are produced at this rate.