British Columbians, especially those living along the south coast of the province, have known that an estimated megathrust magnitude 9 earthquake — the Big One — will hit the region sometime in the future.

Much of its coming existence comes from on the West Coast, including Kuuya GyaaGandal, known as the Sacred One Standing and Moving; the story of Earthquake Foot; and the Nininigamł, or the earthquake mask.

In sa���ʴ�ý, the oral traditions of Indigenous communities are the best resources for transmitting knowledge of events that happened many generations ago, says Sara Shneiderman, an associate professor in the department of anthropology at the University of British Columbia (UBC).

Over the last several decades scientists have become increasingly aware that the , which runs through southwest sa���ʴ�ý, could be the site of a significant earthquake in the future, despite a lack of major seismic activity for over 300 years.

In fact, Shneiderman says she is worried for individuals living in "technically illegal housing," usually basement units.

"The question is, what would people who are living in that kind of situation actually be entitled to in terms of any kind of compensation or relocation support, if they're not actually living in a legal situation? And that applies to all kinds of people, including students here at UBC, as well as young professionals and so forth, due to basically issues within the kind of housing code and zoning that haven't been updated, and haven't been articulated with disaster planning policy," she says.

"Buildings most at risk in Vancouver are what are often classed as heritage buildings. They're built with unreinforced masonry. So for instance, a lot of the older schools but also character houses are not up to contemporary building code... A lot of older buildings simply are not resilient in the way they should be, so that's what's going to disappear if we have a big earthquake."

How can Metro Vancouverites prepare for the supposed Big One?

Shneiderman, like many experts, recommend having an emergency kit. Although supplies might vary, the a week-long supply of non-perishable foods, with a manual can opener; and four litres of water per person, per day for drinking and sanitation.

Also, municipalities offer free workshops for people to create their kits.

The UBC professor also recommends learning about whether one's housing is up to building code.

"If you own your own home, checking if it is up to code. People may not wish to do that because it can be a major financial burden. If it's not, but if you are concerned and if you're doing household renovation anyway, it's a good set of questions to be asking and I think a lot of people don't think that way.

"If you rent, that's also something you can ask landlords about. Again, that may not get you the place that you want."

Shneiderman notes that research shows community members come together to help each other in disaster aftermath.

"If you actually know your neighbours who might need help, and you're in a position to provide that, that's very helpful. People who are already most vulnerable are most at risk: the elderly who live alone, or people experiencing poverty, or otherwise marginalized community members."

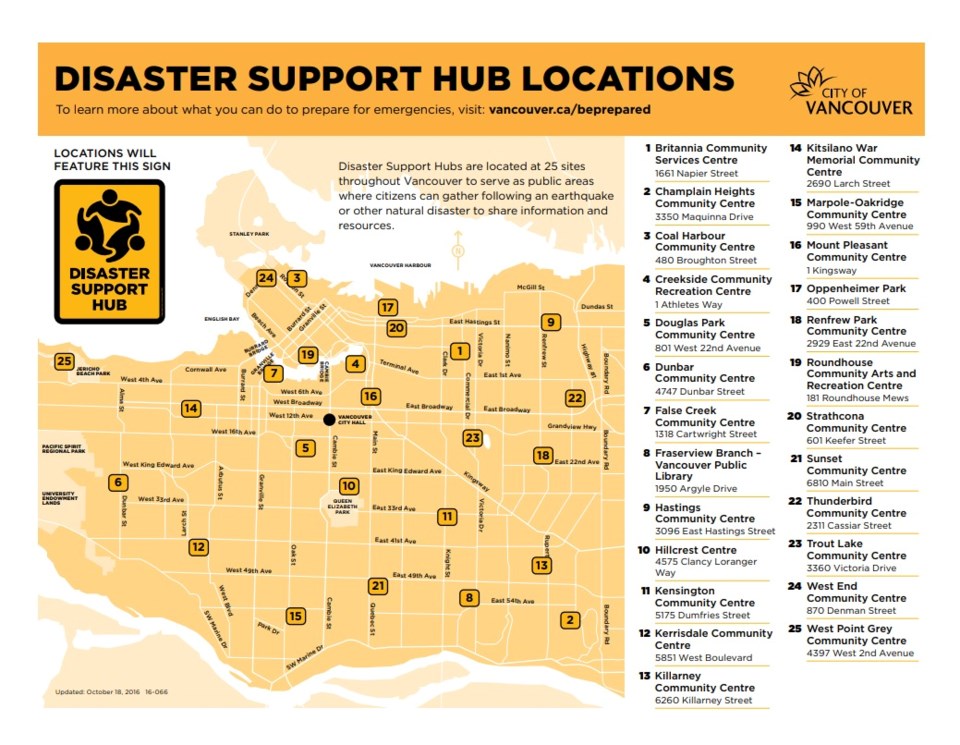

More than anything, Shneiderman advises Metro Vancouverites to learn about their city's resiliency planning. For example, in addition to an emergency kit, the City of Vancouver has 25 sites for people to gather after an earthquake or any other natural disasters — identifiable by yellow signs.