A few years ago, the writer was hospitalized with a potentially fatal case of pancreatitis after taking a banned performance-enhancing drug to lose weight. His psychiatrist said he was trying to kill himself. Auslander, then unemployed, in his 40s, with a wife and two children, disagreed. He said he did it because he was tired of hating himself for being fat and believed that if he were thinner, it might be easier to find work and provide for his family.

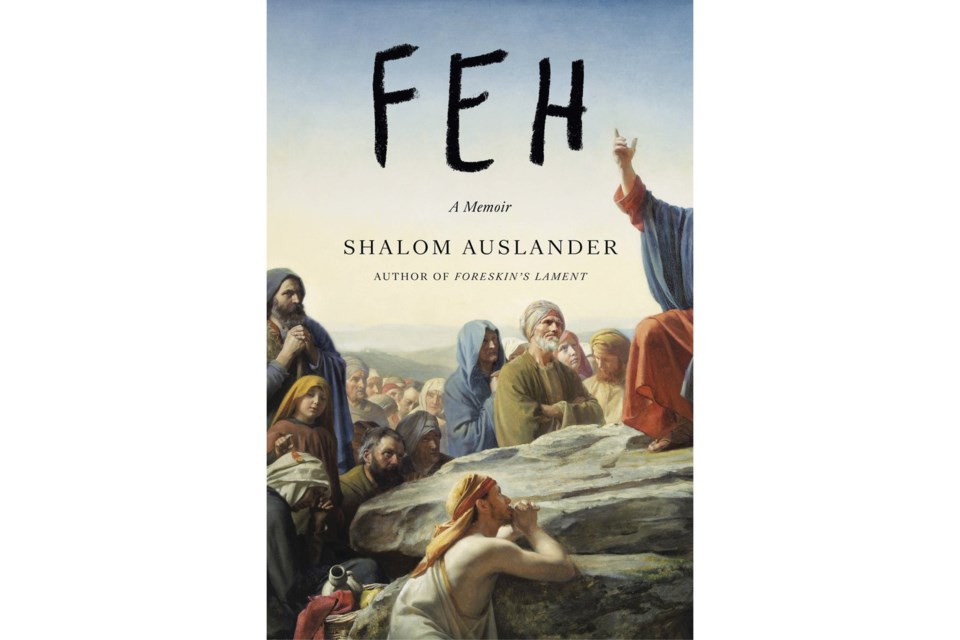

Auslander relates this tale at the beginning of his latest memoir, “Feh,” a poignant, profane, and scabrously funny exploration of the way that organized religion, but also scientists and philosophers, conspire to teach us that we are “feh,” a Yiddish expression of contempt. If you don’t believe this, he argues, consider the fact that according to Genesis, the first human was called Adam, whose name derives from “adamah,” the Hebrew word for dirt.

Auslander says he was inspired to write this sequel of sorts to his acclaimed 2007 memoir, “Foreskin’s Lament,” by his friendship with who died of a drug overdose in 2014. In the Irish Catholic actor, Auslander perceived a kindred soul raised with the same story of “feh” that was drilled into him by the rabbis in charge of his religious education in the ultra-Orthodox Jewish community of Monsey, New York (Auslander originally wrote the since-cancelled Showtime series, “Happyish,” for Hoffman.)

As Auslander attempts to exorcise his demons and rewrite his origin story in a more positive light, the book takes on a “meta” flavor in line with the narrative we humans have been telling ourselves lately about the way we use storytelling to make sense of our lives.

One of his favorite storytellers is Franz Kafka. He recalls falling in love with his stories, the way he laughed at shame and mocked his accusers. “Critics… claimed he was attacking bureaucracy or government or the justice system, but I knew he wasn’t. He was attacking `feh.’ Kafka was the inmate in the cell beside mine, tapping on our shared wall, letting me know I wasn’t alone. This, I had thought, is writing. This is the secular, the free, the accepting.”

For now, Auslander’s story seems to have a happier ending than Hoffman’s, transformed and redeemed by his love for his family and desire to see his boys grow up without the self-loathing he has carried around since he first learned at age 6 that God created man out of dirt and the angels said “feh.”

___

AP book reviews:

Ann Levin, The Associated Press