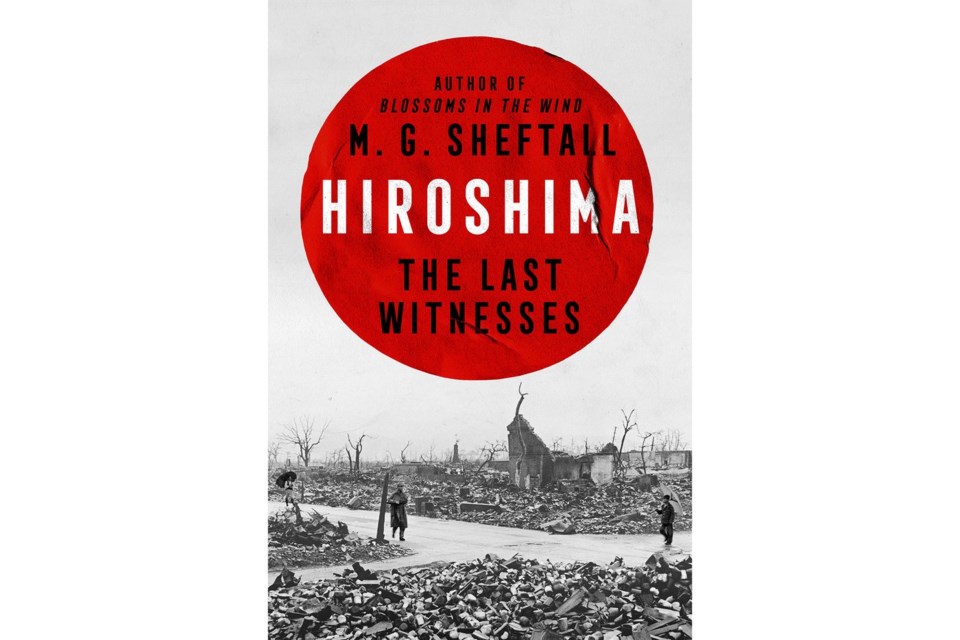

An is so horrific all accounts tend to be quintessential. M.G. SheftallŌĆÖs ŌĆ£Hiroshima: The Last Witnesses,ŌĆØ a carefully and respectfully researched oral history, is no different.

Although the individuals who recount their tales vary, from engineers to schoolgirls, their message is the same: In the words of one survivor, Kohei Oiwa, ŌĆ£If there is a hell, he thought to himself, certainly it must be just like this.ŌĆØ

Oiwa, a junior high school student in 1945, is told to help stack bodies. Charred flesh crumpled in his grip so he held only bones. His is one of many rendered by Sheftall in his blow-by-blow retelling.

The storytelling leads up to Aug. 6, 1945, circles around and around that moment, then describes what it left afterward, weaving in and out of witness accounts.

The experience is tantamount to recalling a giant nightmare so painful itŌĆÖs hard to read in one sitting.

Sheftall, an American who has lived in Japan since 1987, interviewed dozens of survivors, known as ŌĆ£hibakusha,ŌĆØ primarily in Japan but also in Taiwan and Korea. Of his bookŌĆÖs 545 pages, more than 50 pages are taken up by references and notes.

ŌĆ£I would describe not only the bombings themselves ŌĆö something countless authors have done quite effectively before me ŌĆö but also the world those survived had known before the bombs, and the New Japan they helped to rebuild from the rubble and ashes of the old,ŌĆØ he wrote in the acknowledgments.

ItŌĆÖs that story heard, over and over again, from those who lived to tell it, although many more died, tens of thousands, in a flash.

Oiwa, who was 2.1 kilometers (1.3 miles) from Japan's Ground Zero, was in his futon bed ŌĆ£when everything suddenly turned white.ŌĆØ

For a reporter assigned to Japan, with her fair share of hibakusha interviews, parts of the book meant to explain the cultural backdrops seemed a bit lengthy and painstakingly detailed.

But this reporter was also reminded of how the story of Hiroshima is at risk of being forgotten. The hibakusha are now over 90 in age.

Sheftall devotes a whole chapter on debunking the idea of being ŌĆ£vaporized.ŌĆØ The heat and destruction from Little Boy and Fat Man did not make for ŌĆ£waving a magic wand over people, and then, presto change-o, watching them disappear with a nice, clean painless ŌĆśpoof,ŌĆÖŌĆØ he wrote.

Some peopleŌĆÖs faces were literally gone. Others had eyeballs knocked out, dangling from their sockets. Charred black figures wandered through a flattened city, begging for water, ŌĆ£Mizu ŌĆ” mizu,ŌĆØ the title of one of the bookŌĆÖs chapters.

Illnesses from radiation poisoning followed for years. They felt guilt and shame for not having died.

His book tells their stories, in all their ruthless violence and gory pathos, but, most important, as a cautionary tale about the perils of nuclear warfare.

___

Yuri Kageyama is on X:

___

AP book reviews:

Yuri Kageyama, The Associated Press