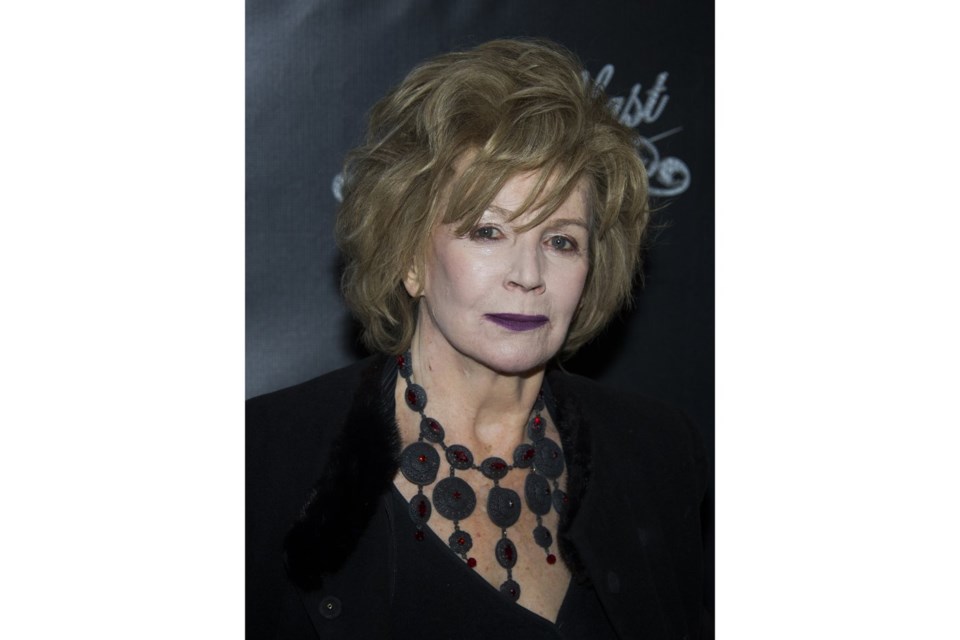

NEW YORK (AP) ŌĆö Edna O'Brien, Ireland's literary pride and outlaw who scandalized her native land with her debut ŌĆ£The Country GirlsŌĆØ before gaining international acclaim as a storyteller and iconoclast that found her welcomed everywhere from Dublin to the White House, has died. She was 93.

O'Brien died Saturday after a long illness, according to a statement by her publisher Faber and the literary agency PFD.

ŌĆ£A defiant and courageous spirit, Edna constantly strove to break new artistic ground, to write truthfully, from a place of deep feeling,ŌĆØ Faber said in a statement. ŌĆ£The vitality of her prose was a mirror of her zest for life: she was the very best company, kind, generous, mischievous, brave.ŌĆØ She is survived by her sons, Marcus and Carlos.

O'Brien published more than 20 books, most of them novels and story collections, and would know fully what she called the ŌĆ£extremities of joy and sorrow, love, crossed love and unrequited love, success and failure, fame and slaughter.ŌĆØ Few so concretely and poetically challenged Ireland's religious, sexual and gender boundaries. Few wrote so fiercely, so sensually about loneliness, rebellion, desire and persecution.

"OŌĆÖBrien is attracted to taboos just as they break, to the place of greatest heat and darkness and, you might even say, danger to her mortal soul," Booker Prize winner Anne Enright wrote of her in the Guardian in 2012.

A world traveler in mind and body, O'Brien was as likely to imagine the longings of an Irish nun as to take in a man's ŌĆ£boyish smileŌĆØ in the midst of a ŌĆ£ponderous London club." She befriended movie stars and heads of states while also writing sympathetically about Sinn F├®in leader Gerry Adams and meeting with female farm workers in Nigeria who feared abduction by Boko Haram.

O'Brien was an unknown about to turn 30, living with her husband and two small children outside of London, when ŌĆ£The Country GirlsŌĆØ made her IrelandŌĆÖs most notorious exile since James Joyce. Written in just three weeks and published in 1960, for an advance of roughly $75, ŌĆ£The Country GirlsŌĆØ follows the lives of two young women: Caithleen (Kate) Brady and Bridget (Baba) Brennan journey from a rural convent to the risks and adventures of Dublin. Admirers were as caught up in their defiance and awakening as would-be censors were enraged by such passages as ŌĆ£He opened his braces and let his trousers slip down around the anklesŌĆØ and ŌĆ£He patted my knees with his other hand. I was excited and warm and violent."

Fame, wanted or otherwise, was O'Brien's ever after. Her novel was praised and purchased in London and New York while back in Ireland it was labeled ŌĆ£filth" by Minister of Justice Charles Haughey and burned publicly in O'Brien's hometown of Tuamgraney, County Clare. Detractors also included O'Brien's parents and her husband, the author Ernest Gebler, from whom O'Brien was already becoming estranged.

ŌĆ£I had left the spare copy on the hall table for my husband to read, should he wish, and one morning he surprised me by appearing quite early in the doorway of the kitchen, the manuscript in his hand,ŌĆØ she wrote in her memoir ŌĆ£Country Girl,ŌĆØ published in 2012. ŌĆ£He had read it. Yes, he had to concede that despite everything, I had done it, and then he said something that was the death knell of the already ailing marriage ŌĆö ŌĆśYou can write and I will never forgive you.ŌĆÖŌĆØ

She continued the stories of Kate and Baba in ŌĆ£The Lonely GirlŌĆØ and ŌĆ£Girls in Their Married BlissŌĆØ and by the mid-1960s was single and enjoying the prime of ŌĆ£Swinging LondonŌĆØ: whether socializing with Princess Margaret and Marianne Faithfull, or having a fling with actor Robert Mitchum (ŌĆ£I bet you never tasted white peaches,ŌĆØ he said upon meeting her). Another night, she was escorted home by Paul McCartney, who asked to see her children, picked up her sonŌĆÖs guitar and improvised a song that included the lines about OŌĆÖBrien ŌĆ£SheŌĆÖll have you sighing/SheŌĆÖll have you crying/Hey/SheŌĆÖll blow your mind away.ŌĆØ

Enright would call OŌĆÖBrien ŌĆ£the first Irish woman ever to have sex. For some decades, indeed, she was the only Irish woman to have had sex ŌĆö the rest just had children.ŌĆØ

OŌĆÖBrien was recognized well beyond the world of books. The 1980s British band DexyŌĆÖs Midnight RunnersŌĆØ named her alongside Eugene OŌĆÖNeill, Samuel Beckett and Oscar Wilde among others in the literary tribute ŌĆ£Burn It Down.ŌĆØ She dined at the White House with then-first lady Hillary Rodham Clinton and Jack Nicholson, and she befriended Jacqueline Kennedy, whom OŌĆÖBrien remembered as a ŌĆ£creature of paradoxes. While being private and immured she also had a hunger for intimacy ŌĆö it was as if the barriers she had put up needed at times to be battered down.ŌĆØ

OŌĆÖBrien related well to KennedyŌĆÖs reticence, and longing. The literary world gossiped about the authorŌĆÖs love life, but OŌĆÖBrienŌĆÖs deepest existence was on the page, from addressing a present that seemed without boundaries (ŌĆ£She longed to be free and young and naked with all the men in the world making her love to her, all at once,ŌĆØ one of her characters thinks) to sorting out a past that seemed all boundaries ŌĆö ŌĆ£the donŌĆÖts and the donŌĆÖts and the donŌĆÖts.ŌĆØ

In her story ŌĆ£The Love Object,ŌĆØ the narrator confronts her lust, and love, for an adulterous family man who need only say her name to make her legs tremble. ŌĆ£Long DistanceŌĆØ arrives at the end of an affair as a man and woman struggle to recapture their feelings for each other, haunted by grudges and mistrust.

ŌĆ£Love, she thought, is like nature but in reverse; first it fruits, then it flowers, then it seems to wither, then it goes deep, deep down into its burrow, where no one sees it, where it is lost from sight and ultimately people die with that secret buried inside their souls,ŌĆØ OŌĆÖBrien wrote.

ŌĆ£A Scandalous WomanŌĆØ follows the stifling of a lively young Irish nonconformist ŌĆö part of that ŌĆ£small solidarity of scandalous women who had conceived children without securing fathersŌĆØ ŌĆö and ends with OŌĆÖBrienŌĆÖs condemning her country as a ŌĆ£land of shame, a land of murder and a land of strange sacrificial women.ŌĆØ In ŌĆ£My Two Mothers,ŌĆØ the narrator prays for the chance to ŌĆ£begin our journey all over again, to live our lives as they should have been lived, happy, trusting, and free of shame.ŌĆØ

OŌĆÖBrienŌĆÖs other books included the erotic novel ŌĆ£August Is a Wicked Month,ŌĆØ which drew upon her time with Mitchum and was banned in parts of Ireland; ŌĆ£Down By The River,ŌĆØ based on a true story about a teenage Irish girl who becomes pregnant after being raped by her father, and the autobiographical ŌĆ£The Light of Evening,ŌĆØ in which a famous author returns to Ireland to see her ailing mother. ŌĆ£Girl,ŌĆØ a novel about victims of Boko Haram, came out in 2019.

OŌĆÖBrien is among the most notable authors never to win the Nobel or even the Booker Prize. Her honors did include an Irish Book Award for lifetime achievement, the PEN/Nabokov prize and the Frank OŌĆÖConnor award in 2011 for her story collection ŌĆ£Saints and Sinners,ŌĆØ for which she was praised by poet and award judge Thomas McCarthy as ŌĆ£the one who kept speaking when everyone else stopped talking about being an Irish woman.ŌĆØ

Josephine Edna OŌĆÖBrien was one of four children raised on a farm where ŌĆ£the relics of riches remained. It was a life full of contradictions. We had an avenue, but it was full of potholes; there was a gatehouse, but another couple lived there.ŌĆØ Her father was a violent alcoholic, her mother a talented letter writer who disapproved of her daughterŌĆÖs profession, possibly out of jealousy. Lena OŌĆÖBrienŌĆÖs hold on her daughterŌĆÖs imagination, the force of her regrets, made her a lifelong muse and a near stand-in Ireland itself, ŌĆ£the cupboard with all things in it, the tabernacle with God in it, the lake with the legends in it.ŌĆØ

Like Kate and Baba in ŌĆ£The Country Girls,ŌĆØ OŌĆÖBrien was educated in part at a convent, ŌĆ£dour yearsŌĆØ made feverish by a disorienting crush she developed on one of the nuns. Language, too, was a temptation, and signpost, like the words she came upon on the back of her prayer book: ŌĆ£Lord, rebuke me not in thy wraith, neither chasten me in thy hot displeasure.ŌĆØ

ŌĆ£What did it mean?ŌĆØ she remembered thinking. ŌĆ£It didnŌĆÖt matter what it meant. It would carry me through lessons and theorems and soggy meat and cabbage, because now, in secret, I had been drawn into the wild heart of things.ŌĆØ

By her early 20s, she was working in a pharmacy in Dublin and reading Tolstoy and Thackeray among others in her spare time. She had dreams of writing since sneaking out to nearby fields as a child to work on stories, but doubted the relevance of her life until she read a Joyce anthology and learned that ŌĆ£Portrait of the Artist as a Young ManŌĆØ was autobiographical. She began writing fiction that ran in the literary magazine The Bell and found work reviewing manuscripts for the publishing house Hutchinson, where editors were impressed enough by her summaries to commission what became ŌĆ£The Country Girls.ŌĆØ

ŌĆ£I cried a lot writing ŌĆśThe Country Girls,ŌĆÖ but scarcely noticed the tears. Anyhow, they were good tears. They touched on feelings that I did not know I had. Before my eyes, infinitely clear, came that former world in which I believed our fields and hollows had some old music slumbering in them, centuries old,ŌĆØ she wrote in her memoir.

ŌĆ£The words poured out of me, and the pen above the paper was not moving fast enough, so that I sometimes feared they would be lost forever.ŌĆØ

Hillel Italie, The Associated Press