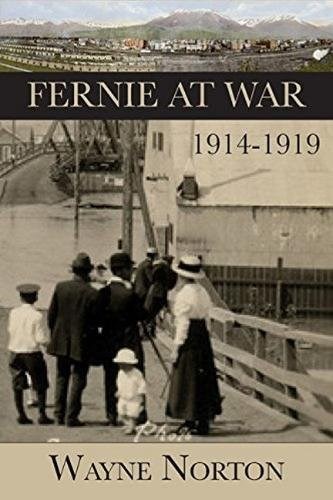

Fernie At War 1914-1919

By Wayne Norton

Caitlin Press, 264 pp., $24.95

��

Every community in British Columbia was hit hard by the First World War, which started with an optimistic swagger but soon was pulled down by the nonstop barrage of death notices and casualty lists in local newspapers.

And every sa���ʴ�ý community has its own stories of woe, how the local sports hero died in the muck in Flanders, or how so many young men never returned, or how the war exposed divisions that took years to mend.

Fernie At War 1914-1919 takes us to Fernie during the war years, and makes us feel as we are part of that city — as uncomfortable as it might have been, given the stresses that seemed to be tearing Fernie apart.

This is more than just a local history, more than a book about Fernie. It forces us to look again at our attitudes toward others around us, and question whether we are hearing the real reasons for political decisions.

In Fernie, the real reasons were not the reasons cited. That left scars that took years to heal.

No sa���ʴ�ý community was hit as hard as Fernie, in the Elk Valley, in the shadow of the Rocky Mountains in the East Kootenay.

Fernie was built on resources — coal mining and lumbering, for the most part. Its population was diverse, made up of families from many different countries.

Ethnic divisions were deep. The labour movement was strong. Proud, loyal Canadians of British descent were ready to fight for the Empire, and were even more willing to start the battle in their home city.

As a result, tensions ran high in the early days of the war, and the first local battleground was laid out as local ethnic groups took sides. Federal measures, such as the declaration that enemy aliens would not be allowed to use or own firearms, did not help.

A judge in Fernie refused to allow enemy aliens to be naturalized, even if their applications had been made before the outbreak of war. At a time when loyalty to the British flag became paramount, some people in Fernie were being denied the chance to show their loyalty.

As the first contingents of recruits in the Canadian Expeditionary Force headed off to Europe, Fernie lost more of its British roots. That added to the feeling among the locals that something had to be done. The high unemployment rate added fuel to the fire.

In June 1915, mine workers declared that they would not work underground with enemy aliens; they cited safety concerns as the reason. Within a matter of days the internment of single miners from the German and Austro-Hungarian empires began.

They were held at Fernie's skating rink. The camp was moved to Morrissey, outside of Fernie, a few months later.

As the war raged on, at home and abroad, the community became even more divided.

The major employer in the area, the Crow’s Nest Pass Coal Company, asked for an end to internments, citing an urgent need for labour. Recruitment of coal miners was prohibited.

Fernie was one of only three communities in sa���ʴ�ý — the others being Alberni and Lillooet — to vote against Prohibition. Fernie voters also endorsed giving the vote to women, although two outlying villages voted against the idea.

If that's not enough, throw in a few mine disasters, strikes and the Spanish flu epidemic to get a sense of how miserable things could be.

With this book, author Wayne Norton, who lives in Victoria, provides the reader with valuable insight into the impact of the war on a small, relatively isolated sa���ʴ�ý��community.

Drawing extensively from the two newspapers printed in Fernie at the time, he describes the serious issues brought by the war, labour strife and the ethnic divides, as well as the lighter moments, including the mayor’s claim that he did not own a dog, and therefore did not need to buy a dog tag.

We read about the cars that were starting to appear on local streets, prominent businesspeople such as Amos Trites and William Wilson, and social events.

Norton doesn’t just write about the history of a small city, he takes us back and makes us feel part of Fernie a century ago. His words are enhanced by photographs, maps and a timeline — all essential ingredients that help the make a history book more accessible and informative, not to mention engaging.

All of this makes Fernie At War a superb book. It digs deep, taking the reader past the obvious stories of local soldiers, and looking at the impact, immediate and long-term, that the war had on the community.

It should be no surprise that Fernie At War has won the community history award presented by the sa���ʴ�ý Historical Federation. Norton’s book not only sets a new standard for local histories, it causes us to reconsider the history of every community.

Dave Obee is editor and publisher of the sa���ʴ�ý.