The reputation of E.J. Hughes in British Columbia is second only to that of Emily Carr, and over his career he painted scenes from all over British Columbia. He especially loved Vancouver Island, and lived most of his 93 years at Shawnigan Lake and Duncan. But due to a unique agreement he made with one man, Max Stern, in 1951, almost every painting he ever created was sent directly to the Dominion Gallery in Montreal.

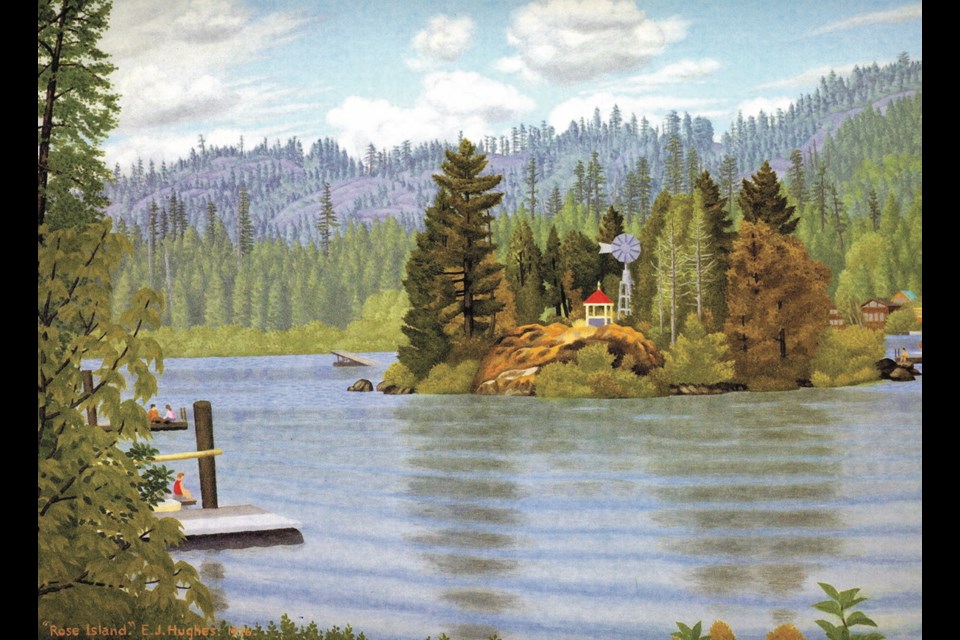

Since 1946, Hughes had moved house in Victoria five times. But even in sleepy Victoria, the noise of the neighbours and their dogs drove him to distraction. By 1951, he was planning an escape, and an advertisement for a property on Shawnigan Lake caught his eye. Shawnigan is a charming lake about seven kilometres long, accessible from the south by the precipitous road over the summit of the Malahat Pass. Real estate was cheaper at Shawnigan, and Hughes was shown a property by the lakeshore, accessible by the meandering Shawnigan Lake Road that crossed the property, running between the house and the waterfront.

Fern, his wife, now disabled by muscular dystrophy, stayed in the estate agent’s car while Hughes took a look around. He was enchanted by the quiet of the place. Never very practical, he didn’t notice that the only running water was from a faucet out back nor that the big old house was heated with a wood stove. Experienced buyers might have considered the amount of groundskeeping that the encroaching forest would entail, but Hughes didn’t think of that. Shawnigan Lake seemed perfect, and despite the drawbacks, he and Fern lived there happily until 1972.

One day in 1951, an unexpected visitor came to Shawnigan Lake and changed the course of their lives. Max Stern had come to Western saąúĽĘ´«Ă˝ to see if he could find a successor to Emily Carr, whose work had been so popular at his Dominion Gallery in Montreal. He visited Lawren Harris in Vancouver — it was Harris who had introduced Carr to the Dominion Gallery in the first place.

While they were having lunch at the Faculty Club at the University of British Columbia, Stern noticed Hughes’ painting Fishboats, Rivers Inlet (1946), which was on loan to the club. Harris was happy to recommend Hughes and set Stern on his way to Victoria to find him.

As it turned out, Hughes had lived at five different addresses in Victoria and then left without a trace. Enlisting the aid of newspaper writer Gwen Cash, Stern eventually traced Hughes through the RCMP detachment at Shawnigan Lake and arrived unannounced at the artist’s home. After an appropriate look at the paintings in the studio, he told Hughes: “I like your work. I’d like to buy it all.” Stern sat at the kitchen table and drafted a brief contract by which, for $500, he bought the contents of Hughes’ studio — “Fourteen paintings and four sketches in oil, as well as 32 pencil studies and four miscellaneous items.”

As it turned out, Hughes had lived at five different addresses in Victoria and then left without a trace. Enlisting the aid of newspaper writer Gwen Cash, Stern eventually traced Hughes through the RCMP detachment at Shawnigan Lake and arrived unannounced at the artist’s home. After an appropriate look at the paintings in the studio, he told Hughes: “I like your work. I’d like to buy it all.” Stern sat at the kitchen table and drafted a brief contract by which, for $500, he bought the contents of Hughes’ studio — “Fourteen paintings and four sketches in oil, as well as 32 pencil studies and four miscellaneous items.”

The sale made Hughes very happy. But there was more. It came as a surprise to him that, as Fern pointed out to him later, Stern wanted to buy everything he made in the future. As each painting was completed, Hughes was to send it to Montreal, and the Dominion Gallery would pay him directly.

This simple contract was in effect until Stern’s death in 1988, and continued until the Dominion Gallery ceased to exist in 2000. Over the years, Hughes dispatched every new painting, and almost every piece of earlier work he had, to the Dominion Gallery. This arrangement might be unique in Canadian art.

With this new arrangement, Hughes could give his full attention to creating the paintings. He didn’t need to sell his work, and he never attended the opening of any of his shows. Over the years, he gave Stern full authority to represent and reproduce his work, and referred all career matters to this trusted dealer and adviser. As he lived in isolation with no artist friends, Hughes had no one but Stern to talk with about art, and their correspondence amounted to 610 handwritten letters. This was essentially Hughes’ only contact with the wider world. In the 36 years they worked together, Hughes and Stern met only four times.

It is true that, in the beginning, Hughes was paid a pittance for his remarkable works, and Stern immediately sold them to the National Gallery of saąúĽĘ´«Ă˝, the Art Gallery of Ontario and the Department of External Affairs — the most prestigious clients in the country. But Hughes’ needs were few, and he trusted Stern entirely. As the years went by, the Dominion Gallery constantly increased the prices it chose to pay him until, in the end, Hughes was receiving cheques for tens of thousands of dollars for individual works of art.

Stern’s eye and his experience in the art market gave him the liberty to make direct — some would say interfering — comments about Hughes’ practices. In 1953, he sent back The Car Ferry at Sidney (1953) requesting that Hughes cut off two inches from the top of the canvas, which the artist obligingly did. This painting was then immediately sold to the National Gallery of saąúĽĘ´«Ă˝. At other times, Stern made comments to Hughes, always in a tactful and gracious way, about colour choices, preferred subjects and compositions, and Hughes paid attention to his valued adviser.

When, in the late 1960s, a consortium of Victoria businessmen contacted Hughes and offered to buy out the contract and pay Hughes more than the Dominion Gallery did, Hughes refused to consider any change in his relationship of trust with Stern.

Excerpted from E.J. Hughes Paints Vancouver Island, TouchWood Editions, © 2018 Robert Amos