The reviewer is editor and publisher of the sa¹úŒÊŽ«Ãœ

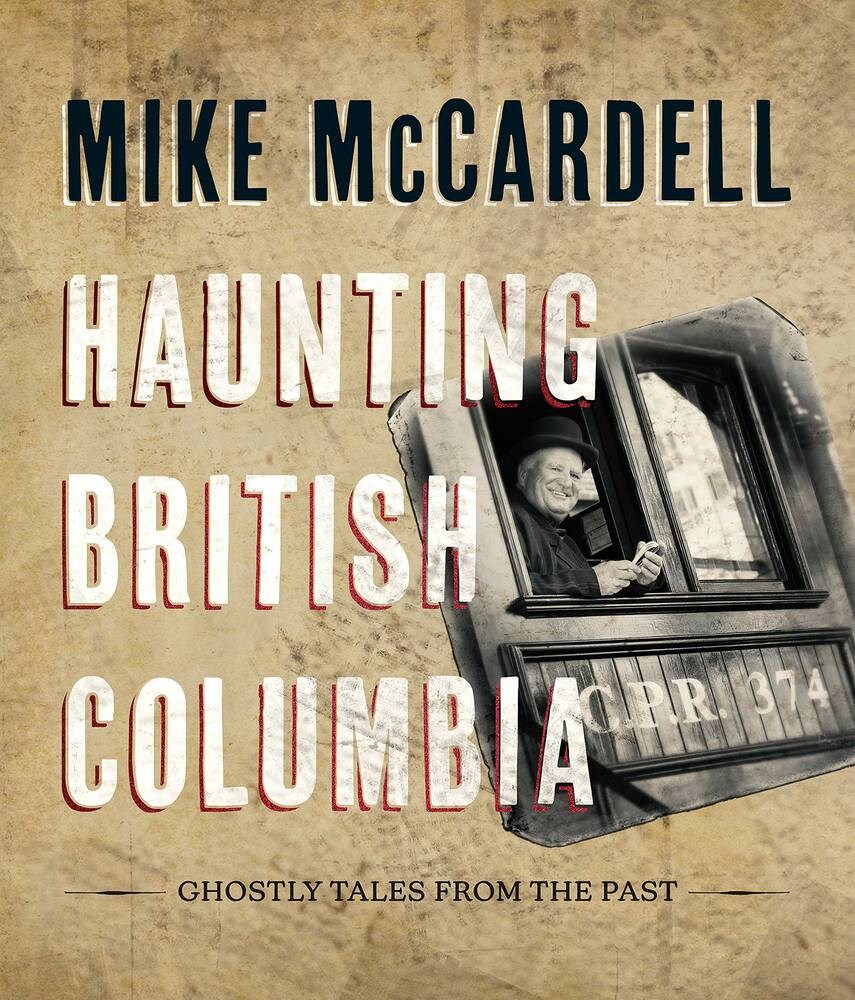

Haunting British Columbia

By Mike McCardell

Harbour, 224 pages, $34.95

We know Mike McCardell from his years as a television journalist, first at a Vancouver station he’d rather not mention, then at another Vancouver station he’s happy to name: CTV.

He is known for his fascinating human-interest stories of interesting people who just might be doing quirky or unusual things. He is also known as an author, having compiled a dozen collections of essays over the years.

Haunting British Columbia is similar – in more ways than the title indicates – to McCardell’s 2013 book, Haunting Vancouver. It has almost four dozen vignettes drawn from our history, as told by the ghost of a real-life person, Jock Linn.

This light approach, enhanced by rudimentary illustrations, is effective, and helps McCardell’s work stand apart from other books on the history shelves.

Yes, there is a Victoria presence here, including cyclist William “Torchy” Peden, one of the world’s highest-paid athletes during the Depression years.

There are chapters on architect Francis Rattenbury (the Empress, the Parliament Buildings) and Amor De Cosmos, the somewhat wacky founder of this newspaper. Over the years, millions of words have been written about those two men, so there is not much more to be said.

A bit lesser known is author W.P. Kinsella, another local who hit the big time and is featured in McCardell’s book. Kinsella gave us the book that led to the Field of Dreams movie, and owed much of his success to his time in Victoria.

Along with running Caesar’s Pizza, near the corner of Douglas Street and Caledonia Avenue, then working at sa¹úŒÊŽ«Ãœ Forest Products and driving for Victoria Taxi to pay the bills, Kinsella took writing courses at the University of Victoria.

Another writer, Robert Service, is also here, although he might barely qualify as British Columbian. He spent time in Victoria, the Cowichan Valley and Kamloops before finding fame and fortune as a poet in the Yukon.

Let’s not forget Lady Amelia Douglas, who was not deemed worthy of respect because of her ancestry: She was half Cree, a quarter French Canadian, and a quarter Irish. Only after her husband James Douglas was named governor did Amelia find acceptance in the local high society. Her presence helps put an Indigenous face in the book’s predominately white crowd.

But, as with many books of this type, McCardell’s goal was not to unearth new details, but rather to bring the old details to a new audience.

It is too bad that the book was not given a more accurate title, one that did not promise something it does not deliver. Perhaps “Haunting Vancouver, Volume Two.” The focus on that little corner of this big province is hard to ignore, given that most of McCardell’s subjects were found there.

Consider the essay entitled “The Big Steal,” about how Victoria, rather than New Westminster, became the capital of the new colony of British Columbia, and in turn the new province. The chapter’s title makes it clear that McCardell/Linn is rooting for the home team, and that’s not Victoria.

At least we have a chapter on George Challenger’s giant relief map of British Columbia, a remarkable post-retirement achievement that was featured at the Pacific National Exhibition for many years. The chapter includes a travelogue of sorts, giving McCardell a chance to mention all sorts of places in the Interior.

But quibbles aside, this book works. The irreverent style of McCardell’s writing — or, at least, the writing of Jock Linn — will draw readers who might otherwise ignore these tales.

Haunting British Columbia aims to take the province’s history to a new audience — never a bad thing — while still offering a fresh perspective for those who are more familiar with it. In other words, it works.