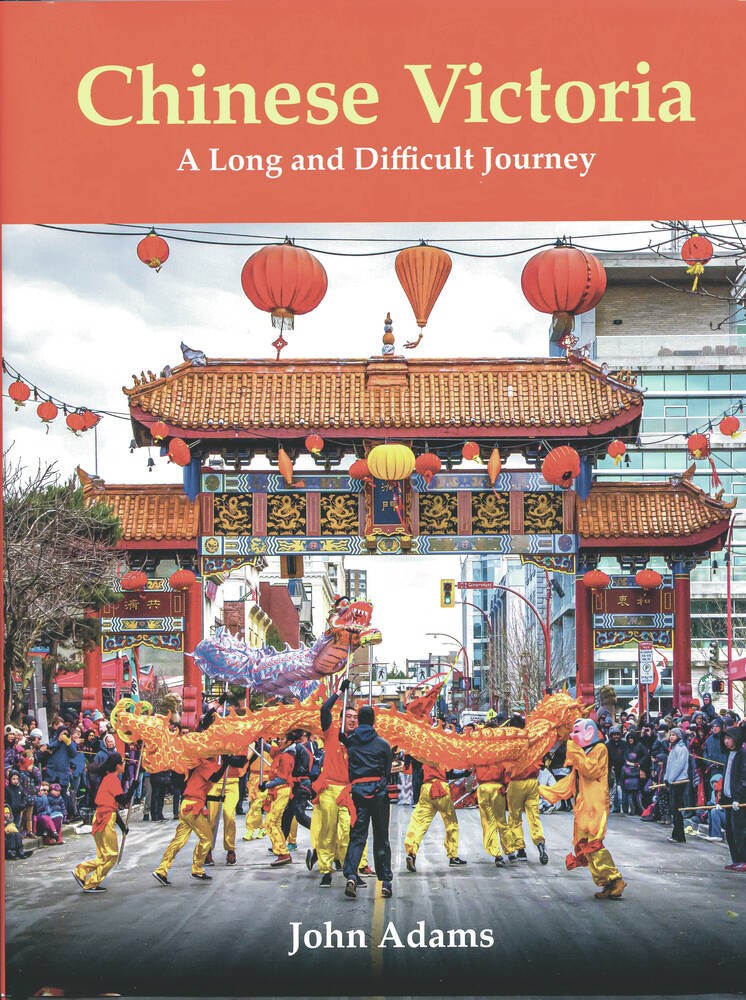

Chinese Victoria: A Long and Difficult Journey

By John Adams

Discover the Past, 475 pages, $80.

The gold rush year of 1858 brought many new people to Victoria, primarily from San Francisco. The sudden explosion in the community, as it was transformed from a fort to a small, but bustling, town, resulted from the arrival of those people, and that sudden growth drew even more people here.

Our dirt streets and hastily built buildings greeted gold seekers, business owners and more.

Following a preliminary trip from San Francisco by three Chinese business leaders in May 1858, a large group of Chinese arrived in Victoria the following month. The next year, more Chinese arrived here, this time directly from Hong Kong.

While some of the Chinese remained in Victoria, setting up wholesale and retail businesses in the area that became known as Chinatown, as well as around Bastion Square, more went to the gold fields to seek their fortunes.

Those who stayed in Victoria have had a lasting impact, since this year marks 165 years of the Chinese presence in Victoria.

In Chinese Victoria: A Long and Difficult Journey, historian John Adams tells the story of the early years of the Chinese in the city – and much more.

To put it quite simply, the book’s first chapter provides background information that sets the stage for their arrival. Subsequent chapters take the reader almost to the present day.

But really, that description does a disservice to Adams and the work he has done in writing and compiling this impressive book. It is a masterpiece, a comprehensive yet highly readable account of a key part of Victoria history that Adams brought together despite obstacles not found in most other research projects.

Consider, for example, the language barrier. Even something basic, such as the names of the people he writes about, can cause problems.

In old documents and reports, which is the first name, and which is the last? Are they always in the proper order? Were they written by people not familiar with the language? In some cases, it could be anyone’s guess which name is correct — and it is possible that a half-dozen different names could refer to the same person.

Adams also had to overcome the racism that as prevalent in early documents. Newspaper accounts about people or events in the Chinese community were not written by Chinese people, and sad to say, it showed.

Those early news stories reflected the belief that members of the Chinese community were different, were doing unusual things, and perhaps were evil, because the writers — and the English-speaking community as a whole — might not have understood what was happening, or what was being said.

It takes determination to cut through the early sources to compile a history of the Chinese community. Thankfully, Adams has that determination, and the result is a magnificent volume.

But let’s put that into perspective, because the problems that Adams had to overcome cannot be compared to the problems faced for decades by Victoria’s Chinese community.

The infamous head tax, charged Chinese immigrants by the federal government, has become well-known in sa╣·╝╩┤½├Į. But what about the Chinese Exclusion Act that followed the head tax, with a goal of ending Chinese immigration rather than simply reducing it?

What about segregation in public schools? The city’s efforts to close Chinese-owned laundries?

Chinese were not allowed to live in Uplands until Raymond Hon Sam moved there in 1948. And the Chinese faced segregation even in death; they were buried in the worst part of Ross Bay Cemetery until they opened their own cemetery at Harling Point in Oak Bay.

Members of the Chinese community dealt with the obstacles they faced as they hit them, and stayed committed to the city. Their successes are a tribute to their abilities in overcoming repeated efforts to discriminate against them.

There have been other attempts to tell the story of the Chinese in this city, but this book — Chinese Victoria — is at another level entirely.

It is loaded with hundreds of photographs, most of them colourized if not originally in colour, and detailed maps help tell the story of Chinatown and the rest of Greater Victoria.

Beyond that, the book will be the ultimate reference on the subject for years to come. It devotes about 100 pages to appendices, endnotes, an extensive bibliography and a comprehensive index.

It’s no surprise that this book has already been given awards by the Hallmark Heritage Society, the sa╣·╝╩┤½├Į Historical Federation and the Chinese Canadian Historical Society. It deserves more.

All in all, this ranks as one of the best books on Victoria history this century. And because the history of the Chinese here cannot be separated from the history of the entire community, this is an essential book for anyone with an interest in Victoria’s past.

The word “masterpiece” should never be used casually. In this case, however, it is warranted.

The reviewer is editor and publisher of the sa╣·╝╩┤½├Į.