Human-caused climate change made dozen of Canadian heat waves more likely over the summer of 2024, according to the first results of a new extreme weather rapid attribution system published Friday by federal scientists from Environment and Climate Change sa国际传媒.

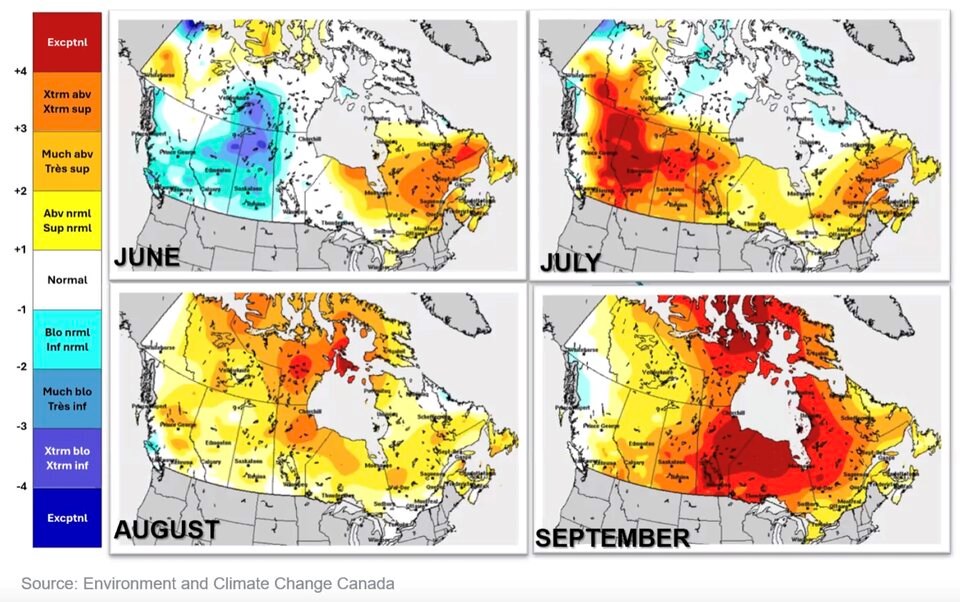

The analysis measured heat waves in nearly every part of the country — in Quebec and Newfoundland Labrador in June, in Western sa国际传媒 in July, sa国际传媒’s North in August and central and eastern parts of the nation in September.

Of the 37 hottest heat waves in sa国际传媒 from June to September 2024, the system found four were at least 10 times more likely to occur as a result of climate warming.

The analysis takes temperature data going back decades and then creates two sets of models. One measures the likelihood of an extreme weather event in our current climate — where more than 150 years of burning fossil fuels has spiked Canadian annual average temperatures 2 C since 1948.

They then compare that to models showing a counterfactual world where humans never ramped up greenhouse gas emissions since the Industrial Revolution.

What emerges is climate change's human fingerprint on individual dangerous weather events.

Nathan Gillet, a research scientist who helped develop the system, said he was surprised to see so many heat waves impacted that much by climate change.

“I think it is striking that we're finding some events in the past summer that were in our highest category — more than 10 times more likely,” he said.

Another 28 heat waves last summer were made two to 10 times more likely due to climate change, while the remaining five were made one to two times more likely.

None of the heat waves analyzed were made less likely because of warming climate.

Impacts felt across sa国际传媒

Some of the strongest impacts from elevated temperatures were found in sa国际传媒's North, where climate change was found to have made heat waves "far more likely."

The analysis found the most powerful temperature anomaly occurred when a heat wave descended on Qikiqtaaluk, or Baffin region of Nunavut, where temperatures remained elevated for a full 25 days. And in the Northwest Territories community of Inuvik, it got as hot as 35 C.

“This is really exceptional in that region,” Gillet said.

In sa国际传媒, the summer started out cool. But when a high pressure system expanded north and east from California, temperatures spiked, setting records across northern Alberta, sa国际传媒, the Yukon and Northwest Territories.

What stood out was the duration of the heat. Heat warnings lasted 18 days straight in places like Cranbrook and Kelowna.

Jennifer Smith, a national warning preparedness meteorologist, said that was a “staggering” length of time compared to previous years.

Rapid attribution to expand to cold weather and precipitation

The results represent the first look at a new “rapid extreme weather event attribution” system which will expand this winter to analyze and connect human-caused climate change with extreme cold.

Federal scientists are also working to expand the system in 2025 to analyze the likelihood climate change is influencing extreme precipitation.

Typically, rapidly measuring climate change’s fingerprint on an extreme weather event takes months to years to carry out. The new Canadian system automatically pulls in weather data. The result, said Gillet, is a system that can produce results within a week.

System meant to help build better infrastructure, let climate reality sink in

The deadliest extreme weather events – heat waves – are expected to become more powerful and more frequent under a warming climate.

Climate projections for the City of Vancouver, for example, have found the number of days the city spends under a heat wave every summer could spike 16 fold compared to the 1990s if the world continues burning fossil fuels under a “business-as-usual” scenario.

Rain, meanwhile, is expected to fall in more powerful bursts, raising the risk of flooding and the costly damage that comes with it.

By understanding the causes of extreme weather, the federal government hopes to better measure the direct and indirect costs of climate change, and how to plan for future events.

Consider the sa国际传媒 floods in 2021, which caused billions of dollars in infrastructure damage, and washed out a number of bridges. When engineers go to rebuild those bridges, they need to know when another similar event will happen in the future. That way they’ll know how strong to make them, said Gillet.

Attributing extreme weather to climate change is also meant to help make the reality of the current world more tangible to Canadians, said the scientist.

“On an individual basis, it's easier to relate to information that a particular heat wave or a heavy rainfall was made twice as likely, for example, by climate change than just some projection that you know is 50 years in the future,” Gillet said.