SOUTHPORT, N.C. (AP) — Jean Heller was toiling away on the floor of the Miami Beach Convention Center when an Associated Press colleague from the opposite end of the country walked into her workspace behind the event stage and handed her a thin manila envelope.

“I’m not an investigative reporter,” Edith Lederer told the 29-year-old Heller as competitors typed away beyond the thick grey hangings separating news outlets covering the 1972 Democratic National Convention. “But I think there might be something here.”

Inside were documents telling a tale that, even today, staggers the imagination: For four decades, the U.S. government had denied hundreds of poor, Black men treatment for syphilis so researchers could study its ravages on the human body.

The U.S. Public Health Service called it “The Tuskegee Study of Untreated Syphilis in the Negro Male.” The world would soon come to know it simply as the “Tuskegee Study” — , an atrocity that continues to fuel mistrust of government and health care among Black Americans.

“I thought, 'It couldn’t be,’” Heller recalls of that moment, 50 years ago. “The ghastliness of this.”

___

The story of how the study came to light began four years earlier, at a party in San Francisco.

Lederer was working at the AP bureau there in 1968 when she met Peter Buxtun. Three years earlier, while pursuing graduate work in history, Buxtun had taken a job at the local Public Health Service office in 1965; he was tasked with tracking venereal disease cases in the Bay Area.

In 1966, Buxtun had overheard colleagues talking about a syphilis study going on in Alabama. He called the Communicable Disease Center, now the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and asked if they had any documents they could share. He received a manila envelope containing 10 reports, he told The American Scholar magazine in a story published in 2017.

He knew immediately that the study was unethical, he said, and sent reports to his superiors telling them so, twice. The reply was essentially: Tend to your own work and forget about Tuskegee.

He eventually left the agency, but he couldn’t leave Tuskegee.

So, Buxtun turned to his journalist friend, “Edie,” who demurred.

“I knew that I could not do this,” Lederer said during a recent interview. “AP, in 1972, was not going to put a young reporter from San Francisco on a plane to Tuskegee, Alabama, to go and do an investigative story.”

But she told Buxtun she knew someone who could.

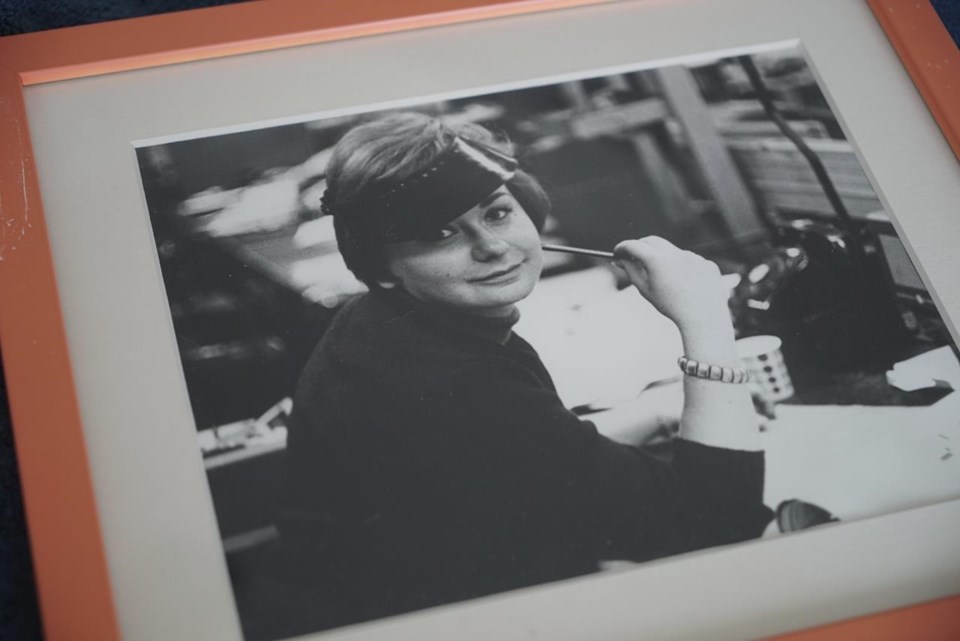

At the time, Heller was the only woman on the AP’s fledgling Special Assignment Team, a rarity in the industry. Still, she was not spared the casual sexism of the era. A 1968 story on the team for AP World, the wire service’s employee newsletter, described the squad as “10 men and one cute gal.”

A caption under the 5-foot-2 Heller’s photo called the “pixie-like” reporter “lovely and competent.”

Lederer knew Heller from their days together at AP's New York headquarters, then at 50 Rockefeller Plaza, where Heller started out on the radio desk.

“I knew she was a terrific reporter,” Lederer says.

During a trip to visit her parents in Florida, Lederer made a short detour to Miami Beach, where Heller was part of a team covering the convention — from which U.S. Sens. George McGovern of South Dakota and Thomas Eagleton of Missouri would emerge as the Democratic presidential and vice presidential nominees.

During a recent interview at her North Carolina home, Heller recalled putting the leaked PHS documents in her briefcase. She says she didn’t get around to reading the contents until the flight back to Washington.

Seated next to her was Ray Stephens, head of the investigative team. She showed him the documents. Stephens realized the government wasn’t denying the study’s existence, just refusing to talk about it.

Heller recalls Stephens saying: “When we get back to Washington, I want you to drop everything else you’re doing and focus on this.”

The government stonewalled her and refused to talk about the study. So, Heller began making the rounds elsewhere, starting with colleges, universities and medical schools.

She even reached out to her mother’s gynecologist, a “straight down the line, middle of the road, superior doctor.”

“I asked him if he’d ever heard about this, and he said, ‘That’s not going on. I just don’t believe it.’”

Finally, one of her sources recalled seeing something about the syphilis study in a small medical publication. She headed to the D.C. public library.

“I asked them if they had any kind of documents, books, magazines, whatever ... that would fit a, what today we would call a profile or a search engine search, for ‘Tuskegee,’ ‘farmers’, ‘Public Health Service,’ ‘syphilis,’” Heller says.

They found an obscure medical journal — Heller can’t recall the title — that had been chronicling the study’s “progress.”

“Every couple of years, they would write something about it,” she says. “Mostly it was about the findings — none of the morality was ever questioned.”

Normally, reporters celebrate these “Eureka” moments. But Heller felt no such elation.

“I knew that people had died, and I was about to tell the world who they were and what they had,” she says, her voice dropping. “And finding any joy in that ... would have been unseemly.”

Armed with the journal, Heller went back to the PHS. They caved.

She says the lede of the story — the first paragraph or sentence of a news article — came to her quickly.

“Marv Arrowsmith, the bureau chief, walked by my desk and, I said, ‘Hey, Marv. Will you publish this?’” she recalls. “And he read it and he looked at me and he said, ‘Can you prove it?’ I said, ‘Yes.’ He said, ‘You got it.‘”

An AP medical writer helped interview doctors for the story. Within just a few short weeks, the team felt they had enough to publish.

Arrowsmith suggested they offer the story first to the now-defunct Washington Star, if it promised to run it on the front page.

“The Star was a highly respected PM (afternoon) newspaper, and if they took it seriously, others might follow,” Heller says.

____

The story ran on July 25, 1972, a Tuesday. It was a harrowing tale.

Starting in 1932, the Public Health Service — working with the famed Tuskegee Institute — began recruiting Black men in Macon County, Alabama. Researchers told them they were to be treated for “bad blood,” a catch-all term used to describe several ailments, including anemia, fatigue and syphilis. Treatment at the time consisted primarily of doses of arsenic and mercury.

In exchange for their participation, the men would get free medical exams, free meals and burial insurance — provided the government was allowed to perform an autopsy.

Eventually, men were enrolled. What they were not told was that about a third would receive no treatment at all — even after penicillin became available in the 1940s.

By the time Heller’s story was published, at least seven of the men in the study had died as a direct result of the affliction, and another 154 from heart disease.

“As much injustice as there was for Black Americans back in 1932, when the study began, I could not BELIEVE that an agency of the federal government, as much of a mistake as it was initially, could let this continue for 40 years,” says Heller. “It just made me furious.”

Nearly four months after the story ran, the study was halted.

The government established the Tuskegee Health Benefit Program to begin treating the men, eventually expanding it to the participants’ wives, widows and children. A class-action lawsuit filed in 1973 resulted in a $10 million settlement.

The last participant died in 2004, but the study still casts a long shadow over the nation. Many African Americans cited Tuskegee in refusing to seek medical treatment or participate in clinical trials. It was even cited more recently as a reason not to get the COVID-19 vaccine.

At 79, Heller is still haunted by her story and the effects it had on the men and women of rural Alabama, and the nation as a whole.

For the story, Heller would win some of journalism’s highest honors — the Robert F. Kennedy, and Raymond Clapper Memorial awards. (Carl Bernstein and Bob Woodward of The Washington Post, writing about the Watergate scandal, finished in for the Clapper Award.)

Hanging in her office is a copy of the front-page byline she got in The New York Times, exceedingly rare for an AP staffer. But the hype surrounding Tuskegee would play a big role in Heller’s decision to leave the AP in 1974.

“I felt after all of the brouhaha over ... Tuskegee, and what came after it, that I should move on,” she says. She went on to a three-decade career that would take her from the hills of Wyoming to the beaches of South Florida.

These days, Heller spends her time cranking out fiction. She’s five books into a mystery series featuring Deuce Mora, a hard-driving female reporter who is a very un-pixie-like 6 feet tall.

Despite her distress over the state of the news business, she has never thought about returning to journalism.

“You can’t go home again; I firmly believe that,” she says. “And I don’t want to be competing against myself or against expectations.”

When asked if she regretted giving up what is arguably one of the great scoops in American journalism, Lederer replied: “Possibly, you know, a little bit.” But she knew the story was bigger than her or Heller or any individual reporter.

“What I cared about most was that this seemed to be a horrible and deadly injustice to innocent Black men,” says Lederer, who was the first woman assigned full time to cover the Vietnam War for the AP and remains its chief U.N. correspondent.

“And for me, the important thing was to verify it and to see that it got out to the broader American public — and that something was done to prevent any such experiments from happening again.”

Heller agrees.

“The story isn’t about me anyway,” she says. “It’s about them.”

Allen G. Breed, The Associated Press