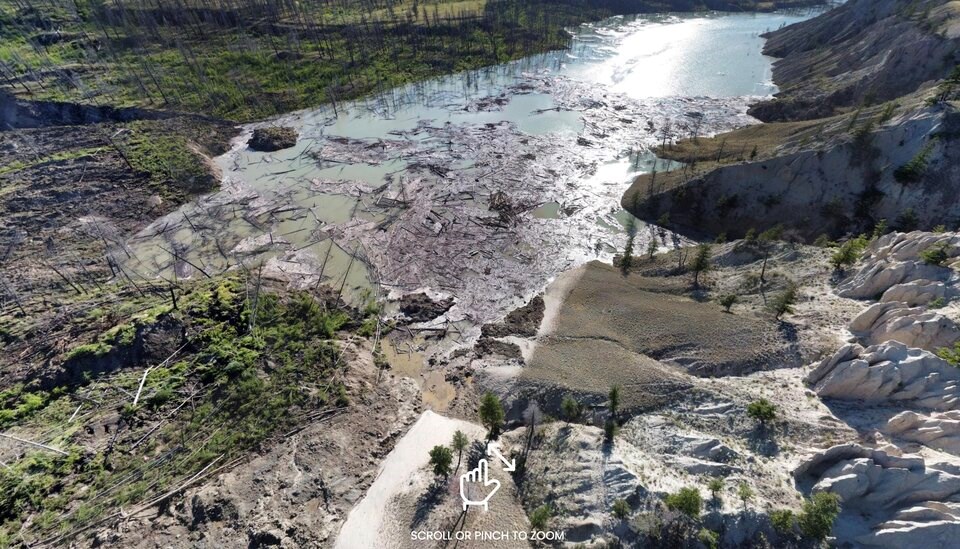

Under the cover of darkness, a hillside overlooking the banks of the Chilcotin River began to collapse. When officials from the sa���ʴ�ý government surveyed the site the next morning, the July 30 landslide had created a dam of rock and soil 600 metres wide and 30 metres deep.

About 30 kilometres upstream of the Fraser River, vast quantities of water pooled behind the choked tributary. As water ate into the landslide dam, emergency officials warned the sudden erosion of debris could lead to a catastrophic failure with floodwaters swamping shorelines all the way to Metro Vancouver.

Alec Wilson got a call from Emergency Management BC on the morning of Aug. 1 — the same day the Tŝilhqot’in National Government declared a state of emergency.

"They said, 'Look we need eyes on this thing. This is a crazy landslide that might affect a lot of people,'" remembers Wilson. "'How quickly can you deploy?'"

A former helicopter pilot and now the chief operating officer at the Vancouver-based Spexi Geospatial Inc., Wilson’s team had flown a number of tailored drone missions across sa���ʴ�ý, monitoring rail lines, inspecting dams and surveying construction sites.

In the summer of 2023, Spexi had stepped into its first emergency, helping regional districts and Emergency Management BC access a bird’s-eye view of scorched infrastructure, devastated homes, and what had survived during the Kelowna and Shuswap wildfires.

"We learned this works and it works fast," said Wilson, who flew drone missions at the same time helicopters bucketed fires.

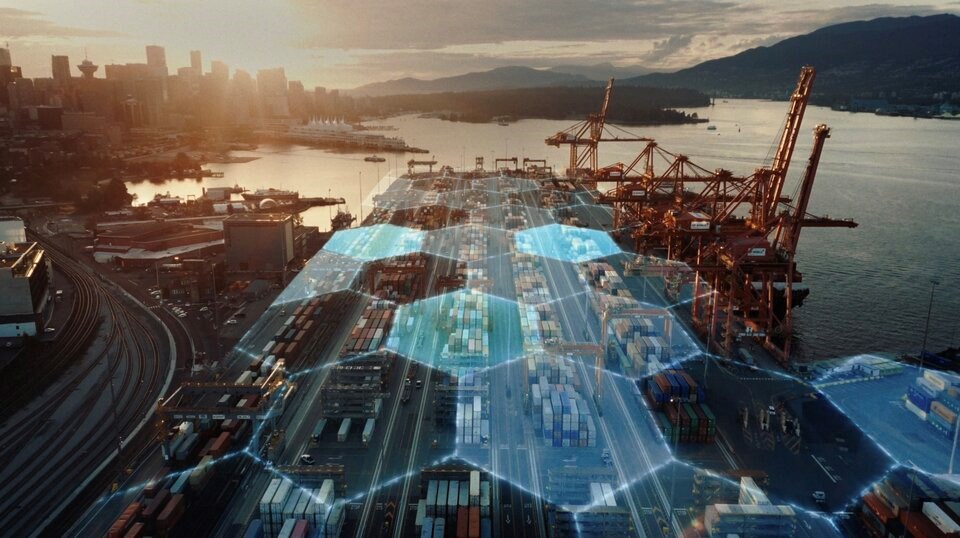

Outside of an emergency, the company has also quickly moved to democratize its aerial imaging platform. Instead of sending its own pilots to capture images from the sky, over the last 18 months, it had built a stable of amateur drone enthusiasts across sa���ʴ�ý

Today, that model has created a visual aerial database that spans 131 sa���ʴ�ý communities in what the company describes as "Google Streetview of the sky."

"What we have is the largest drone imagery network on Earth," said Wilson.

Proving to sa���ʴ�ý it works

Founded in 2017, the start-up is one of several companies and government agencies looking to fill the gap between commercial satellite imaging and traditional aerial photography.

In sa���ʴ�ý, the federal government has moved to build the , a new generation of satellite meant to help firefighting agencies and researchers track infernos and better predict fire behaviour. It will also help governments plan evacuations and even track air quality and carbon emissions, says the federal government.

But WildFireSat is not scheduled to launch until 2029, and even when it’s operational, the national scope of its mission means resolution will be limited to 200 metres.

Spexi’s panoramic and overhead visual database, on the other hand, can capture images down to 2.8 centimetres of resolution. That’s more than three times better than what cameras from aircraft usually capture and more than 30 times higher quality than the average commercial satellite — all at a fraction of the operating cost, said CEO and president Bill Lakeland.

Spexi's drone network cannot feasibly monitor forests across sa���ʴ�ý like a satellite. But it can be tasked to fly cities and in specific disasters. Another advantage of drones over satellites is they can often avoid high cloud cover, according to experts who have trialled the technology.

David Huntley, a research scientist at Geological Survey of sa���ʴ�ý who monitors landslides across sa���ʴ�ý’s steep valleys, said Spexi has developed a piece of technology that fills a gap between low-resolution commercial satellite technology, expensive aerial photography and on-the-ground surveys.

He said surveys of landslides in the Thompson River Valley used to take weeks, but on their last trip, Huntley and his colleagues used the Spexi network to fly four landslides in two days.

"In the evening, we had the data processed," said Huntley, whose government research team was one of the first to trial the technology. "We could see where tension cracks appeared in a new landslide."

"The quicker that we can get information to emergency services — highways, the railway people, even firefighters — the better."

In a paper published in 2023, Huntley concluded that the Spexi platform "provides rapid landslide monitoring capability with cm-scale precision and accuracy." The study notes the platform has the potential to model impacts from tsunamis and monitor everything from active faults and volcanic hazards to power transmission right-of-ways and the melting of permafrost.

"There’s tons of public safety benefits to the world," added Huntley. "Let alone all of military applications."

"The Department of National Defence are highly interested."

A crowd-sourced drone network

Lakeland, who grew up on Vancouver Island and now lives in Delta, traces his obsession with aerial photography back to a fortuitous class he took at Simon Fraser University in the 1990s as an engineering student. One day in a geography class he was tasked to delineate orchards in the Naramata Bench. Peering at the nearly foot-long negatives, he was hooked.

"I was like, 'Oh, my goodness, I have to be the guy that takes these pictures,'" he said.

Lakeland would spend about two decades capturing aerial photographs across North America before starting Spexi. A lot of that work included assessing forests after wildfires and helping cities map infrastructure. As the years passed, all those flights burned a lot of fossil fuels, and that bothered him.

"We go through a lot of fuel in aircraft. And I was like, 'I’d love to change this up, find a more scalable way of doing this,'" he said. "How do you fly the City of Vancouver with drones?"

When Lakeland launched Spexi seven years ago, many foresaw drones . But that dream has faced a number of challenges in recent years. Amazon’s decade-long to launch drone-delivered parcels has yet to fully take off despite plans for by the end of 2024.

On the battlefield, artificial intelligence is already opening up a new operational world — from drone swarms to autonomous targeting of bomb-laden drones in the seconds before impact. In recent years, many civilian aviation authorities have moved to , but remain cautious to approve standardized flights beyond a pilot’s visual line of sight over urban populations.

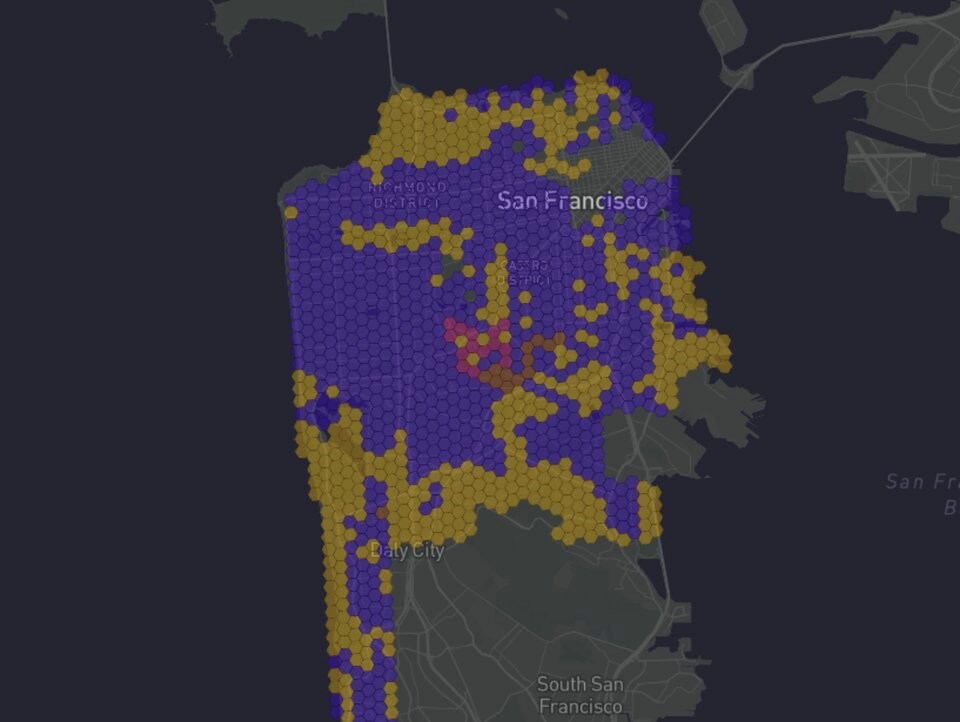

To get around that problem, Spexi recruits and pays anyone with a micro-drone to fly automated flight paths across 10-hectare hexagonal plots of land.

Because the drones are smaller and therefore less dangerous, they have fewer restrictions and don’t require a licence. The automated flight paths the company provides further reduce the risk of collisions with another aircraft or human head, said Lakeland.

Once pilots finish their flights, they can upload the images to the cloud database within hours, adding another piece to a growing aerial atlas.

Spexi's crowd-sourcing model has caught the eye of venture capitalists. Lakeland says Spexi now has about 20 employees working out of its Vancouver office with plans to double over the next year.

But first, the company has to prove its technology is fast and efficient. As part of a plan to improve wildfire preparedness, Spexi is currently under contract with the federal government to prove it can quickly capture high-quality drone images over wide areas.

Drone network blankets 131 sa���ʴ�ý communities

Since April 2024, the company has paid hundreds of pilots to fly nearly 40,000 flights. Together, they have captured more than 400,000 hectares, or a million acres, of ultra-high resolution drone imagery, most of which spans 131 sa���ʴ�ý communities.

Outside of sa���ʴ�ý, the company has expanded its visual database with flights across Mexico, the U.K. and a number of U.S. cities like San Francisco, Austin and Houston. In Galveston, Texas, captured aerial imagery shows detailed roof damage from a recent hurricane, something Lakeland says could be used for rapid insurance assessments.

"The beauty is we can spin this up anywhere," he said.

Spexi’s growing visual network is regularly updated to see change over time. In the event of a disaster, the idea is to mobilize the company’s drone pilots to an affected area. Anyone with the updated URL can digitally hover over a city or wildland boundary to see block by block what it looked like before and after the arrival of a wildfire, flood, storm or earthquake.

"We've flown these small towns across the province. We have our network stood up there. Now, if there is a fire or if there's a flood or some kind of a storm, we can re-task the network to fly very quickly and get these visualization insights back the same day," Lakeland said.

"It's like Google's Streetview in the sky, essentially blanketing cities."

Unlike Google Streetview, Lakeland said the automated flight plans fly above the threshold where you can identify people and read licence plates.

The imagery is still detailed enough to apply artificial intelligence to detect changes across the landscape — from damaged buildings and cracked pavement to the potential of forests to burn near the urban edge.

"[Are] there down trees? Is it down power lines? Show me all the missing roof shingles across the city. Show me where the pooling water is," Lakeland said. "And so you can train computer vision to search all this data to find those pieces.”

Under Spexi’s current contract with the Canadian government, the company is now working on training its algorithms so the computer models better recognize different tree species and whether they are alive and standing or knocked over.

If the computer model identifies a lodgepole pine, for example, it might give it a flammability ranking of 89 per cent. If that tree is half dead or close to other dead lodgepole pines, the ranking goes up again, Lakeland said.

The CEO said he is focused on applying the Spexi network to emergency preparedness and helping cities plan. But it’s not hard to imagine applying the visual database to real estate websites like Zillow, short-term rental services like Airbnb, or for HVAC or landscaping companies who want to do an assessment, said Lakeland.

"They can just do their quotes and not burn gas driving around. It's really like getting people out of cars is what it is. The last mile delivery piece for utilities," he said.

A longer shot, said Lakeland, would be to integrate the Spexi network into Google or Apple’s map applications, or form the real-world digital backbone for augmented reality platforms like the Metaverse or gaming.

"They are extremely interested in what we're doing. We just need a critical mass of it to be able to make sense for them," he said.

'Groundbreaking' technology in an emergency

Like the wildfires of 2023, the Chilcotin landslide offered a test of how the Spexi drone network could be applied far from its current city-focused model.

The morning the landslide triggered an emergency order, Wilson said the company pinged its Discord servers with an urgent request for pilots. Roughly a dozen responded, and two were deployed from Kamloops with Starlink satellite internet terminals to fly automated flight paths and .

Within hours of the initial phone call, emergency officials had everything they needed to create three-dimensional models of the landslide dam. Wilson said those models helped guide flood warnings and evacuation orders for thousands of people and livestock downstream of the slide.

In a social media , Minister of Water Land and Resources Stewardship Nathan Cullen shared the Spexi images, describing them as “incredible.”

As Spexi’s Graham Anderson, who coordinated the pilots, put it: “It's something they've never had before.”

When the Chilcotin River landslide gave way, a torrent of water, trees and debris equivalent to about 200 million dump truck loads was sent downriver. By the time the morass reached the mouth of the Fraser River and flushed out to sea, communities along the way, , had the information they needed to warn their residents and shut down riverside parks and boardwalks.

Huntley, who was on site for three of the 10 days drone pilots flew over the landslide, said the near-real time, high-resolution images and movie footage enabled provincial agencies to make detailed models of landslide dimensions, levels of flooding and lake inundation, as well as decisions about evacuations.

He said the experience made him appreciate "how groundbreaking a tool the Spexi application is" for emergency management.

When asked how the drone company's technology helped the provincial response, a spokesperson for Cullen’s ministry said Spexi’s daily capture and sharing of real-time data “was crucial for helping ministry staff do their jobs” while creating “transparency and trust” with the public.

“The drone team's work not only improved our understanding of the situation, but it also set a new benchmark for handling similar events in the future,” said the spokesperson in an email.