On the 150th anniversary of Emily Carr’s birth, we revisit early Victoria — the town of the artist’s childhood — through her own eyes, with a selection of passages from her books, including The Book of Small and Growing Pains.

We’ve provided contemporary photographs for some things that haven’t changed much, and historical pictures for those that have — the James Bay bridge that Emily used to cross regularly, for example, is long gone, replaced by a causeway after the tidal flats were filled in for construction of the Empress Hotel. But the church her family attended, the Church of Our Lord, still stands near what was once the mouth of the flats.

Passages were selected by Jan Ross, the former curator for Emily Carr House, who has edited them for clarity and brevity.

Just a note: In her writing, Emily often referred to herself as “Small.”

1) Emily Carr House (her mother’s bedroom, where she was born, is at top left)

“I was born during a mid-December snow storm; the north wind howled and bit. Contrary from the start, I kept the family in suspense all day. A row of sparrows, puffed with cold, sat on the rail of the balcony outside Mother’s window, bracing themselves against the danger of being blown into the drifted snow piled against the window. Icicles hung, wind moaned, I dallied. At three in the morning I sent Father ploughing on foot through knee-deep snow to fetch Nurse Randal.”

— From Mother, Growing Pains

2) Mrs. McConnell’s Farm (Michigan and what was then Birdcage Walk)

“Mrs. McConnell was a splendid lady; I liked her very much indeed. She had such a large voice you could hear it on Toronto Street, Princess Ave and Michigan Street all at once. She was so busy with all her children and cows and pigs and geese and hens that she had no time to be running after things, so she stood in the middle of her place and shouted and everything came running …. something was always running to Mrs. McConnell. She sort of spread herself over the top of everything about the place and took care of it.”

— From Carr Street to James’ Bay, The Book of Small

3) James Bay Bridge (now Causeway)

“James Bay district, where Father’s property lay, was to the south of the town. When people said they were going over James’ Bay they meant that they were going to cross a wooden bridge that straddled on piles across the James’ Bay mud flats. At high tide the sea flooded under the bridge and covered the flats. It receded again as the tide went out with a lot of kissing and squelching at the mud around the bridge supports, and left a fearful smell behind it which annoyed the nose but was said to be healthy.”

— From James Bay and Dallas Road, The Book of Small

4) Father’s warehouse/store (1107 Wharf St.)

“My Father was a wholesale importer of provisions, wines and cigars. His store was down on Wharf Street among other wholesale places. The part of Wharf Street where Father’s store street stood had only one side. In front of the store was a great big hole where the bank of the shoreline had been dug out to build wharves and sheds …. At the opposite side of the Wharf Street hole stood the Customs House, close to the water’s edge. Made of red brick, it was three storeys high … very dignified.”

— From Father’s Store, The Book of Small

5) Government Street at Christmas

“On Christmas Eve Father took us into town to see the shops lit up. Every lamp post had a fir tree tied to it …Victoria streets were dark; this made the shops look all the brighter. Windows were decorated with mock snow made of cotton wool and diamond dust. Drygoods shops did not have much that was Christmassy to display except red flannel and … fur muffs and tippets. […]

“It was the food shops that Merry Christmassed the hardest. In Mr. Saunders,’ the grocer’s, window was a real Santa Claus grinding coffee. The wheel was bigger than he was. He had a long beard and moved his hands and his head … In the window all around Santa were bonbons, cluster raisins, nuts and candied fruit, besides long walking sticks of peppermint candy ….. The food shops ended the town, and after that came Johnson Street and Chinatown, which was full of black night. Here we turned back towards James’ Bay, ready for bed.”

— From Christmas, The Book of Small

6) Church of Lord at Christmas

“All the week before Christmas we had been in and out of a sort of hole under the Reformed Church [of Our Lord], sewing twigs of pine onto long strips of brown paper. These were to be put round the church windows, which were very high. It was cold under the church and badly lighted. We all sneezed and hunted round for old boards to put beneath our feet on the earth floor under the table where we sat pricking ourselves with holly, and getting stuck up with pine gum…. Everything unusual was fun for us children. We felt important helping to decorate the Church.”

— From Christmas, The Book of Small

7) Driard Hotel (View Street)

“Victoria’s top grandness was the Driard Hotel; all important visitors stayed at the Driard. To sit in crimson plush armchairs in enormous front windows and gaze rigid and blank at the dull walls opposite side of View Street so close to the Driard Hotel that they squinted the gazer’s eyes, to be stared at by Victoria’s inhabitants as they squeezed up and down the narrow View Street, which had no view at all, was surely something worth a visit to the capital city.

“The Driard was a brick building with big doors that swung and squeaked. It was red inside and out. It had soft red carpets, sofas and chairs upholstered in red plush and velvet curtains, red also. All its red softness sopped up and hugged noises and smells. Its whole inside was a jumble of stuffiness … when you came out of the hotel you were so soaked with its heaviness you might have been a Driard sofa.”

— From Grown Up, The Book of Small

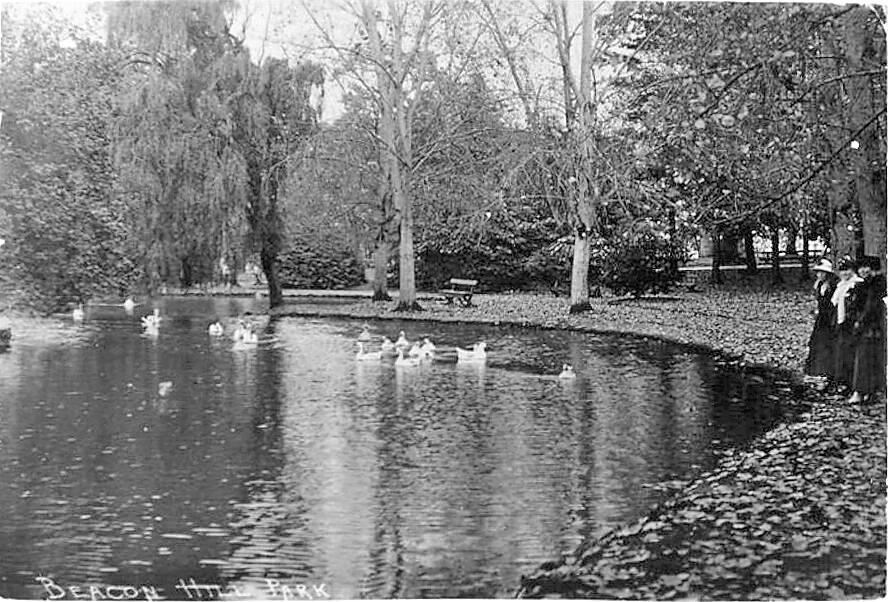

8) Beacon Hill Park

“Shall we have a picnic?”… I was so proud. Mother, who always shared herself equally among us, was giving to me a whole afternoon of herself!

“It was wild lily time. We went through our garden, our cow-yard and pasture, and came to our wild lily field … Between our lily field and Beacon Hill Park was nothing but a black tarred fence … I stepped with Mother beyond the confines of our very fenced childhood. Pickets and snake fences had always separated us from the tremendous world. Beacon Hill Park was just as it had always been from the beginning of time, not cleared, not trimmed. Mother and I squeezed through a crack in its greenery … soon we came to a tiny, grassy opening, filled with sunshine and we sat down under a mock-orange bush, white with blossom and deliciously sweet….Our picnic that day was perfect. I was for once Mother’s oldest, youngest, her companion-child …

“It was only a short while after our picnic that Mother died.”

— From Mother, Growing Pains

9) Ross Bay Cemetery

“The old Quadra Street Cemetery was a lovesome place, but now it was full as the law would allow. So they put a chain and padlock round the pickets of the gate to keep the dead in and the living out, and dedicated a new portion of cleared raw ground at Ross Bay for Victoria’s burying. It was a treeless, wind-swept place, of gravely soil and blaring sunshine. One side of the ‘New Cemetery’ was bounded by the sea. The other side was bounded by the highway, over which ran periodically a noisy rural tram line.”

In 1886, Carr’s mother died and her father gathered the children together to choose the family burial plot, which Carr describes as the first time her father had allowed his children to have a voice in family affairs.

“I choose what seemed to me the only comfortable spot in all the cold bleakness. It has two willow trees growing on it, the only trees in the whole New Cemetery. It lies in a little hollow right in the centre of Ross Bay’s curve. The sea gulls swoop in from one end of Ross Bay, circle the two willows and circle out again, carrying their cries out to sea.

“Father frowned. ‘I do not like that low-lying dip, small. It is damp, unhealthy.’ ‘Do dead people mind damp?’ [Carr wonders].

“Father wanted the best there was for Mother. High, dry, healthy. He bought on the ridge. He leant a little heavily on Small’s shoulder as he climbed the slight incline as though he felt the weight of his three score years and ten. He saw Small turn for a last look at the two willow trees, after his decision was made. ‘Small, you got your love of trees from me.’ He smiled down at the little girl, feeling her disappointment.

“Up on the ridge the wind always blew and the sun always scorched and brittled the grass between the graves …. The sea gulls never troubled to come that far inland to cry for the dead, nor were there any drooping willow boughs to sweep across the graves. Small used to wonder if the dead felt any healthier up there than down in the hollow.”

— From The Family Plot, This and That: The Lost stories of Emily Carr, edited by Ann-Lee Switzer.