My school days in elementary school began with a bike ride of five kilometres, followed by a spirited playground game of Red Rover (sometimes called British Bulldog) before the bell rang and lessons began.

Recess involved more playground games that were later resumed at lunchtime.

Classroom lessons fit in there somewhere, and most days there was a game of pickup cricket or touch rugby after school, followed by the bike ride back home.

The time before dinner was usually filled with a lot of running around playing war games in the forest that adjoined our subdivision — this was in the early 1950s, so Americans vs. Germans — or more cricket with a tennis ball and a garbage can as the wicket in the cul-de-sac where our neighbourhood was located.

We did not have daily P.E., which would have represented an unnecessary add-on to all of this frantic activity.

I suspect that before the pandemic, before online learning at home, before masks and social distancing, a normal school day for most kids consisted of numerous variations of my own childhood school day with its full slate of physical activities.

I say that with confidence having been, for several years, the principal of an inner-city K-7 school of 450 kids.

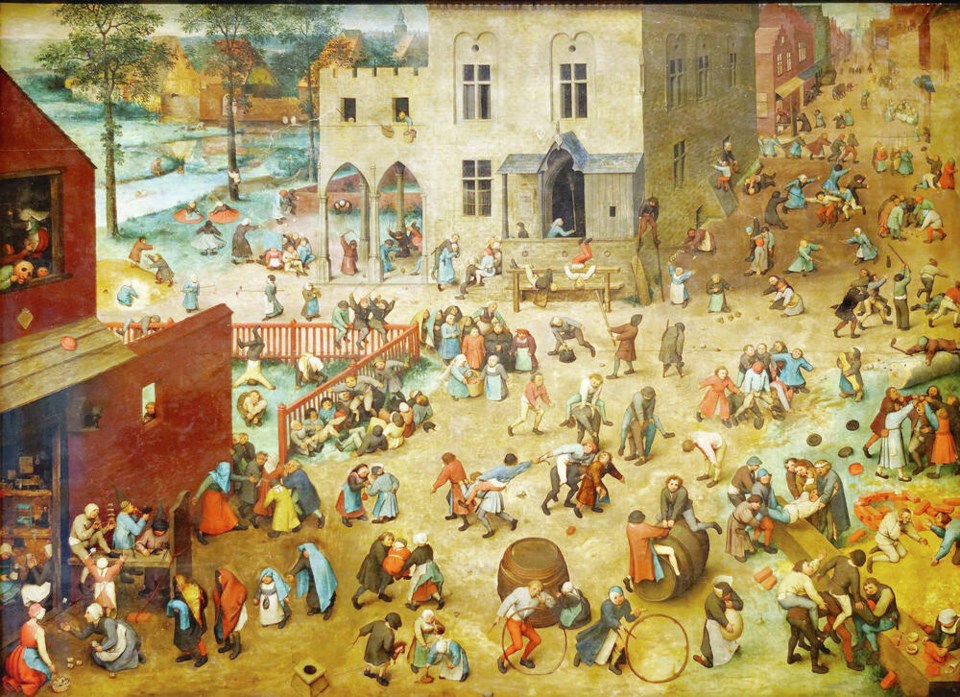

Time before classes, at recess, lunchtime and even for a while after classes always reminded me of Children’s Games, by Flemish Renaissance artist Pieter Bruegel the Elder.

Painted in 1560, the work pictures 200 or so children energetically playing something like 80 different games in a village square.

Fast forward to 2021.

The unanticipated consequence of the pandemic on school life is that all this school-day kid-driven activity was brought to a grinding halt by the necessity of sedentary online learning, masks and social distancing.

The collateral damage is that the full impact of the pandemic on kids’ health and fitness won’t fully be known for some time.

However, a researcher at Dalhousie University’s Healthy Populations Institute has been busy capturing the experiences of children, families and communities as they adjust to living with COVID-19 and the challenges that come with it.

In collaboration with ParticipACTION and Outdoor Play sa国际传媒, Dr. Sarah Moore, an assistant professor at Dalhousie’s School of Health and Human Performance, conducted a national survey to assess how children and families adapted their behaviours during COVID-19.

The survey found that less than 3% of kids were meeting the 24-hour movement guideline, dropping to 1.5% for kids with disabilities.

“COVID-19 restrictions made leaving the house and doing the physical activities we love more challenging — which means kids are moving less, sleeping more, and spending more time on their phones and tablets,” says Moore.

All this is being held responsible for at least a short-term spike in childhood obesity, with rates of overweight and obesity in five- through 11-year-olds rising nearly 10 percentage points since the first few months of 2020.

According to the ParticipACTION site, only 4.8 per cent of children ages five to 11 and less than one per cent of teens were meeting 24-hour movement behaviour guidelines during COVID-19 restrictions, compared with the 15 per cent of all children and teens (ages five to 17) prior to the pandemic.

Compounding the concern was the fact that many students were also missing out on recess and extracurricular sports.

Even daily P.E. classes can’t compensate for this loss of daily activity.

To make matters worse, there are signs that P.E. is taking second place to the scramble to make up for core subject time lost because of school shutdowns.

Canadian experts warn it will take more than just a return to classes to get kids moving again.

A survey from the research unit at Children’s Hospital of Eastern Ontario in Ottawa found children’s movement declined abruptly at the beginning of the pandemic — only 2.6 per cent of children and youth met the 24-hour movement guidelines from the Canadian Society for Exercise Physiology and the Public Health Agency of sa国际传媒.

“We saw this massive decline, abruptly, perhaps expectedly, because the messaging, you might recall at the time, was stay home,” said Mark Tremblay, the Ottawa-based senior scientist who conducted the CHEO research.

On the plus side, Tremblay says he has seen some evidence of an increase in unstructured play. He encourages parents to continue to give kids free time outdoors, in their neighbourhoods, “playing ball hockey, throwing a Frisbee around, playing hide and seek, doing the things that were done in the past.”

And no, I’m not an old guy reminiscing about my childhood pastimes, but I do remember my mother issuing after-school instructions along the lines of: “Go outside and play — be back before dark.”

We made up the rest ourselves.

Geoff [email protected]