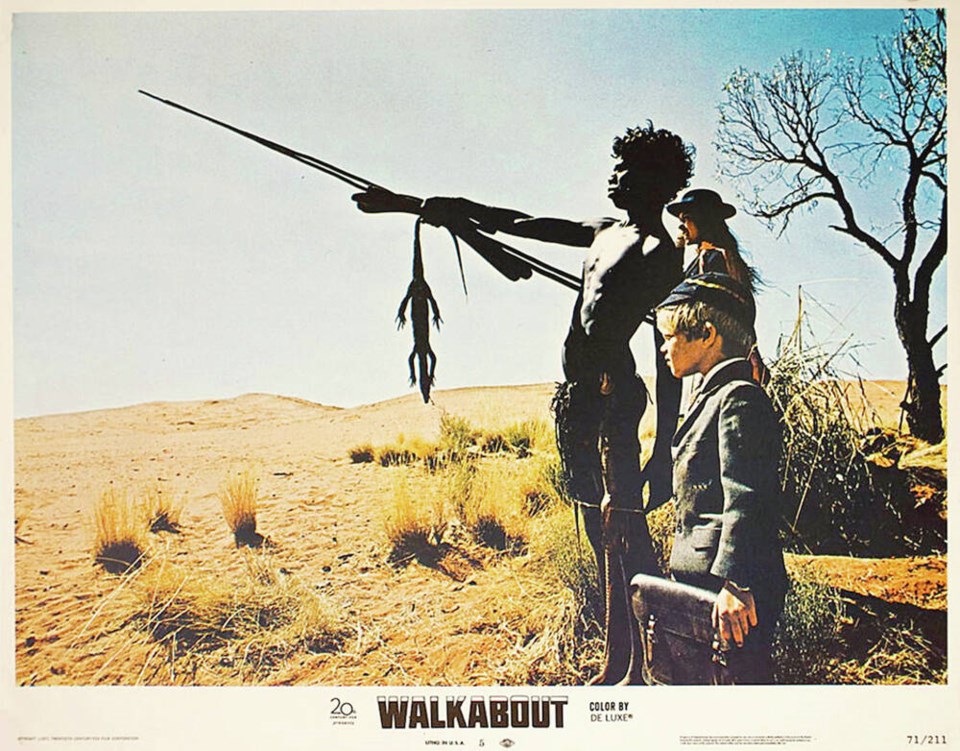

The news of the passing last week of aboriginal Australian actor and dancer David Gulpalil will, for many educators, bring back memories of the iconic 1971 movie Walkabout.

In the movie, two children, dressed in their school uniforms, escape into the desert-like wilderness of the Outback when their father, driven mad by failure in business, attempts to kill them.

Within hours, they are exhausted, lost and helpless, unable to find food or water. With no hope of finding their way back, they seem certain to die.

Then they are found and cared for by a young Aboriginal Australian boy on his “walkabout,” played by a youthful Gulpalil.

The “walkabout” in tribal lore was a six-month endurance test during which a boy must survive alone in the wilderness and return to his tribe an adult, or die in the attempt.

Thanks to the guidance of Gulpalil’s character and his ability to find sustenance where none appeared to exist, the lost school boy and his sister not only endure, but learn to merge with the land, which is so sacred to their Aboriginal saviour.

The movie inspired Simon Fraser University professor emeritus Maurice Gibbons to write an article for the educator bible Phi Delta Kappan. The iconic article became the most requested reprint in the history of the journal.

Gibbons found the movie to be a “haunting work of art” and also “a haunting comment” on the practice of North American education, inasmuch as Gulpalil’s “walkabout” character faced a severe but extremely appropriate trial, one in which he had to demonstrate the knowledge and skills necessary to make him a contributor to the tribe, rather than a drain on its meagre resources.

“By contrast,” wrote Gibbons, “the young North American is faced with written examinations that test skills very far removed from the actual experience he will have in real life,” adding that “he writes; he does not act.”

“He solves familiar theoretical problems; he does not apply what he knows in strange but real situations.”

By contrast, the “walkabout” trial common to many tribal communities at that time required young men to undertake an extended period of solitude at a crucial stage of their maturation.

The young Aboriginal boy, confronted with a challenge, not only learns about his own competence, but also about his individual inner or spiritual resources.

For his Western counterpart, suggested Gibbons, school is always a crowd experience.

Seldom separated from their classes, friends or family, North American teenagers have little opportunity to confront their anxieties, explore their inner resources, and come to terms with the world and their future in it.

Other sociologists and anthropologists have also written about the significance of the tribal “walkabout,” whereby when the young Aborigine returns, his readiness and worth have been clearly demonstrated to his tribe. He has shown his ability to survive and they, the tribe, need him.

He is their hope for the future.

By contrast, wrote Gibbons, the 12 years of education leading to North American graduation and preparation and trial in our society are “incomplete, abstract, and impersonal; and graduation is little more than a party celebrating the end of school.”

The walkabout model, suggested by Gibbons in his vision for education, suggests that our solution to this problem must measure up to a number of criteria.

First of all, it should be experiential and the experience should be real rather than simulated.

Second, it should be a challenge that extends the capacities of the students, leading them to consider personal limitations only as barriers to be broken through, not goals that are easily accessible.

Thirdly, such a school should require students to be significantly self-directed.

As Margaret Mead pointed out in Growing Up in Samoa, the major challenge for young people in our society is in learning how to make decisions.

The test of a “walkabout”-inspired version of modern education, said Gibbons, “is not what he can do under a teacher’s direction, but what the teacher has enabled him to decide and to do on his own.”

In the “walkabout” model for education, the responsibility for learning is on the student, not the teacher.

All of which brings to mind Dr. Phillip C. Schlecty, a leader in the world of school reform, who once suggested that “contemporary schools are places where the somewhat younger go to watch the somewhat older work.”

Schlecty, like Gibbons, suggests that the truly innovative school is a learning organization in which students assume much greater responsibility for their own educational “walkabout.”

Geoff Johnson is a former superintendent of schools.