This is one of a series of columns by specialists at the Royal sa���ʴ�ý Museum that explore the human and natural worlds of the province.

Invasive exotic species are a global problem, and the mild climate of southwestern sa���ʴ�ý is particularly prone to the establishment of foreign species.

sa���ʴ�ý has a long history of exotic introductions, and with each new species, the natural character of the province is changed forever. Some introduced species, such as the European robin, vanished without a trace. At the other end of the spectrum, green crab, English ivy and Himalayan blackberry have spread rapidly and overwhelm areas where they are established.

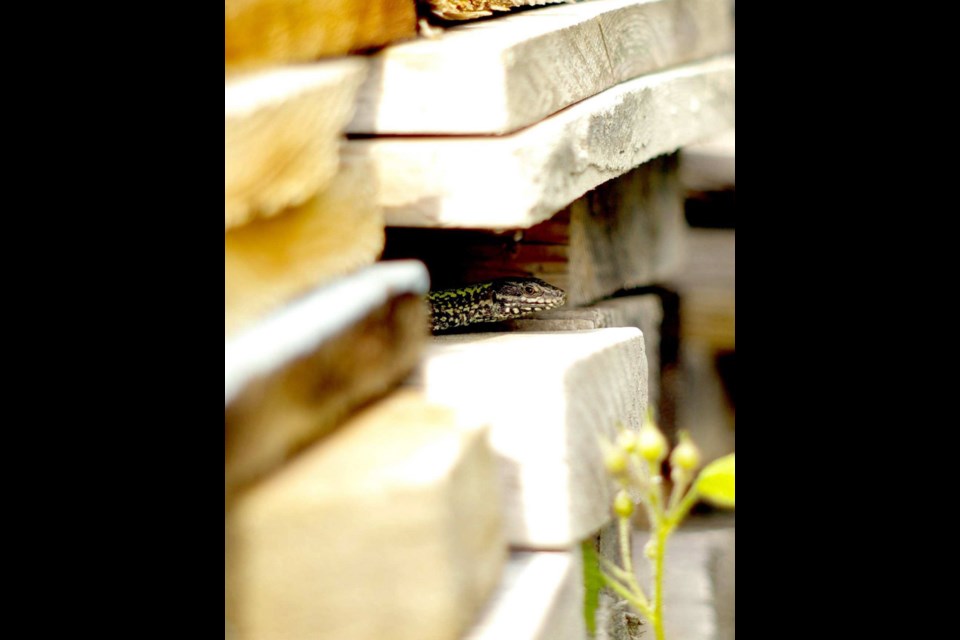

Very few reptile species have been released in sa���ʴ�ý, and of these, only the European wall lizard (Podarcis muralis) has proven to be invasive. In the early 1970s, 12 wall lizards from Northern Italy were released onto Vancouver Island, and by 2004, they had not spread far.

In the past decade, though, we have seen a rapid spread of this invasive lizard, and it now ranges across the Saanich Peninsula south to Triangle Mountain and Metchosin. In the past three to five years, new populations were detected in Campbell River, Cobble Hill, Mill Bay and Shawnigan Lake, a single lizard appeared in North Vancouver, and another appeared in Osoyoos.

How are they getting around? They’re lizards, so they crawl. But we’re also moving them — most are moved unintentionally, others are deliberately moved to new locations. They get around in hay bales, horse or livestock trailers, even firewood.

You might move a nest of lizard eggs in a potted plant. Later that summer, the eggs hatch and you have seven or eight lizards in your garden. Those lizards reproduce, and the next year you have 20, and the year after that: 100. That’s how fast they’re populating new areas.

This is not a lizard that is spreading far and wide in natural areas of sa���ʴ�ý; it is spreading in urban areas. They do well around humans because we create rock walls (they are called wall lizards for a reason) and fences. We have structured gardens with plenty of sun and shelter, and in our gardens there are few predators. People have seen American robins, garter snakes, northwestern crows and small hawks (either Cooper’s or sharp-shinned hawks) attacking wall lizards, and of course, wall lizards are cannibalistic.

Domestic cats also try (and usually fail) to catch these lizards. There are many lizards with re-grown tails — evidence of how frequently lizards are attacked and escape. There are few controls on the lizard population. They can even survive partial freezing of their body fluids.

The rapid spread of European wall lizards will be the subject of a peer-reviewed research paper in collaboration with researchers from the Habitat Acquisition Trust and the Ministry of Environment.

As a part of my involvement with the Inter-Ministry Invasive Species Working Group, I am also watching Osoyoos to see if a population has established itself near the U.S. border. So far, we have not had any reports of more wall lizards in Osoyoos, only a single lizard that was a stow-away in a shipment of grapes — but we have to remain vigilant.

While the lizards on Vancouver Island are beyond control, a population in Osoyoos should be eradicated to prevent spread in the Okanagan region.

Why do this work? Because there’s still much to learn about their behaviour and about their possible impacts on native species. Although European wall lizards have been here for 40 years, we have little idea what they eat, and we have yet to determine their impact on terrestrial, arboreal and aerial arthropods and other invertebrates.

They are thought to eat earthworms, flies, earwigs, termites, ants and other crawling insects, as well as spiders and perhaps isopods. Given observations in West Vancouver of a wall lizard killing a young garter snake and that wall lizards are cannibalistic, it is possible that they also eat newborn alligator lizards (Elgaria coerulea) and eggs and hatchlings of the endangered sharp-tailed snake (Contia tenuis).

Since it is unlikely that wall lizards will be eradicated from Vancouver Island given the size of the current population, it is important that we examine the diet of this exotic species and evaluate the risks to species at risk and other native species of southern Vancouver Island.

Exotic-species introductions and spread are a global concern; what happens here can help others assess their invading species. The invasion of our region might seem insignificant on a global scale, but I’ve already been contacted by a scientist who wants to visit and study the lizards to compare them to the same species in England.

A colleague from Germany is also watching what happens here with interest; in his country, wall lizards are native in some places and invaders in other parts (the native range of these lizards is from Spain, north to Belgium and Germany, and across Europe southeast to Greece and Turkey). The world is watching.

It’s also worth studying this dispersal given the context of climate change. The potential for European wall lizard colonization and range expansion is increased significantly by climate warming. What we learn about wall lizards in sa���ʴ�ý will be invaluable for prediction of the spread and impact of this species elsewhere.

Studying the dispersal of European wall lizards has also provided me with an opportunity to tap into the power of citizen science. I have been asking British Columbians to report when they find wall lizards.

For example, based on conversations I’ve had with homeowners in the Doncaster School area, I know the age of the population of the European wall lizard is probably six years. And the population is spreading in this neighbourhood between 40 and 100 metres a year.

How do I know when lizards are new to an area? I ask homeowners specifically whether they had lizards in 2016, or when they first noticed lizards. It is not an exact science, but it does give us an idea how fast lizards are spreading. That’s the power of local knowledge and citizen science. Their observations are helping me add detailed data to my own wall-lizard map.

If you’ve recently seen European wall lizards in your neighbourhood, you can help me track their dispersal. Take a photo if you can, and send me a note with your street address. I’ll add your sighting to my database. You can reach me at: [email protected].

Gavin Hanke, curator of vertebrate zoology, joined the Royal sa���ʴ�ý Museum in 2004. He publishes research on newly discovered marine and freshwater fishes in British Columbia, and also works with sa���ʴ�ý’s Ministry of Environment to collect and monitor exotic vertebrates. He has a special interest in the role of the pet trade, angling industry and importation of live food fishes as a source of exotic/invasive animals.