Warning: This story contains mentions of self-harm.

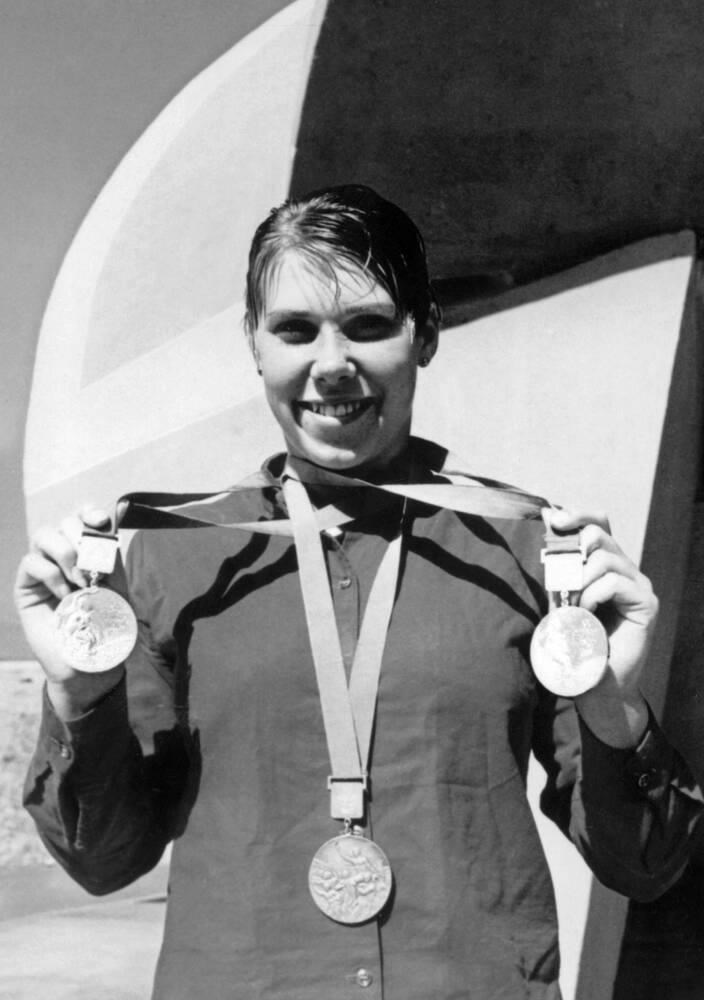

Elaine Tanner was 17 years old when headlines screamed she was a loser because instead of gold, she won two Olympic silver medals for sa���ʴ�ý.

Nicknamed Mighty Mouse due to her ferocity in the water and diminutive stature, Tanner, 73, has come a long, difficult way since the 1968 Olympic Games, where she was favoured to win gold in two backstroke events.

Tanner also won a bronze medal in the team relay in Mexico City, and her three medals represented 60 per cent of sa���ʴ�ý’s medal haul, but the media wanted to know why there was no gold.

“It was horrible,” said ski hall-of-famer Nancy Greene, who was working at the 1968 Games as a TV colour commentator.

Greene, speaking by phone from Sun Peaks in the Interior, doesn’t recall who the reporter was — a TV personality from Toronto — but she and North Vancouver’s Harry Jerome watched in horror as the reporter stuck his microphone in teenaged Tanner’s face while the swimmer froze in shock.

“Elaine was still dripping, she’d swum faster than she’d ever swum in her life, a personal best, lost in a close race, and he said: ‘Elaine, why did you lose?’

“She was just crushed. There were a couple more questions, Jerry and I looked at each other and said we had to get her out. We ran and grabbed her and a towel, and took her out of there.

“It was just awful, that moment scarred her for a long time.”

It did.

“I was broken,” Tanner says now.

She walked away from competitive swimming at age 18. Always an “A” student, she enrolled in university but couldn’t focus.

She got married at age 21 and began a family, but the marriage didn’t last. By the mid-1980s, Tanner was living in her car. She had eating disorders, anxiety attacks and suicidal thoughts.

By her 37th birthday, she felt she couldn’t go on. It was February 1988.

“I so clearly remember, it was a bone-chilling, damp and dreary day, I was all alone in my old worn-down Subaru hatchback. In the car were a few suitcases of my clothes I’d thrown together and my nana’s old sewing basket, which held my Olympic medals, now just as weathered as I was,” she said.

“This old car and the remnants of my tattered life was all I had left.”

She can still feel the cold spray and drizzle hitting her face as she made her way awkwardly over slippery rocks to the ocean’s edge in West Vancouver, a Canadian hero lost, alone and utterly defeated.

“There was no more down — I’d hit rock bottom of my soul,” she said. “How easy it would be to just slip between the waves and disappear.

“I felt so at home in the water. It had been my friend and comfort zone for so many years — maybe it could now forever wash away the pain and deep ache in my soul.”

Then, as darkness engulfed her, a tiny voice in her head reminded her of her two amazing children and chastised her for giving up when she had accomplished so much.

“ ‘Why me?’ ” she asked the voice. “‘Have faith,’ it said. Those words saved my life that day.”

Two months later, she met John Watt.

‘Knight’ time

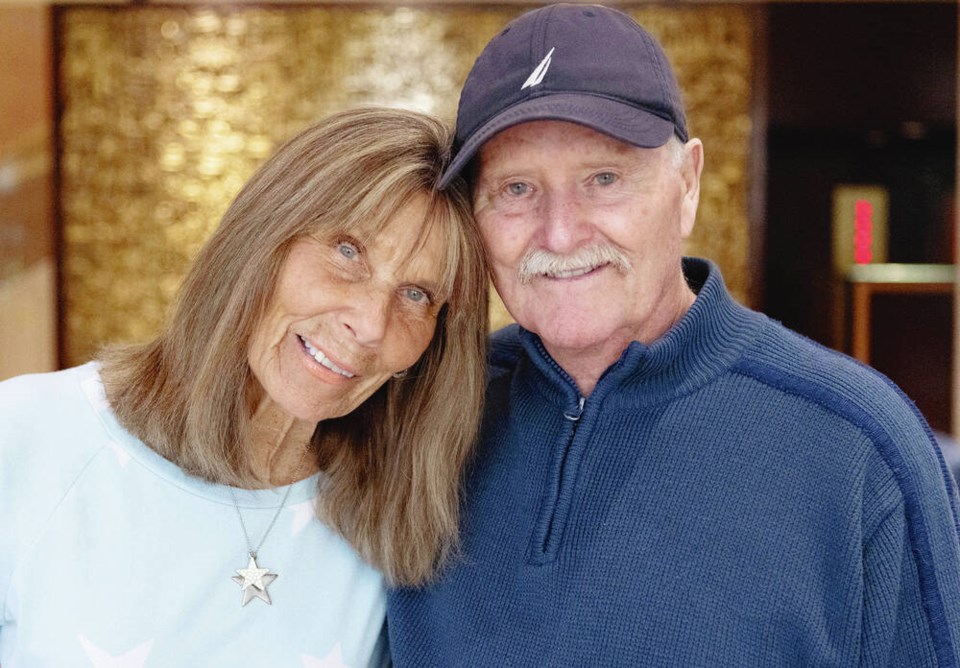

Married for 35 years now, Tanner and Watt split their time between Vancouver Island, with her children and grandchildren, and Watt’s family in Ontario.

They first met on a blind date just blocks from where the two of them shared Tanner’s story recently over cups of coffee in a quiet corner of a downtown Vancouver restaurant, after taking a ferry from Vancouver Island.

“I call John my knight in rusty armour,” Tanner said with a smile as she reached out to gently touch her husband’s arm.

Watt was crashing with a buddy just before Expo ‘86 when his host asked if he would like to go on a blind date with a friend of his girlfriend’s, someone named Elaine Tanner.

“Her name didn’t ring a bell,” Watt said.

Despite it being the lowest point in her life, Tanner agreed to meet Watt at a Robson Street cafe. When he first saw her, he was so concerned that he gave her some money to buy groceries.

“When we met, I just saw a person I liked, but I wondered why she was in so much pain,” he said.

Most people had no idea what Tanner was going through, including Greene. “I once met Elaine at a sports hall-of-fame dinner. She’d come over from Victoria and she asked if I could give her a ride back to the ferry.

“During the drive, Elaine confided that she came to the banquet because she was hungry.”

Tanner always had trouble talking about her torment, unable to unpack the emotional baggage buried deep within. With Watt as a partner, she began her healing — counselling, meditation, mysticism and, most importantly, no longer holding everything inside.

“There are two parts to my life,” Tanner said: “pre-John and John in my life. We are each other’s worlds.”

Watt encouraged her to write things down.

She penned a children’s book, illustrated by Dennis Proulx, about unconditional love and friendship (Monkey Guy and the Cosmic Fairy); she’s written 300 pages so far of a draft autobiography; and she has chronicled her life, thoughts and feelings on her websites, Quest Beyond Gold, and elainetanner.ca.

It’s easier, she said, to write about the pain that has accompanied her than it is to talk about what happened at that Olympic pool a half-century ago.

“I didn’t realize it then, but I was traumatized,” Tanner said. “I blanked out. I don’t remember anything. I don’t remember getting my medals, nothing. It’s a complete blank to me.”

The list of her medals and multiple world records in the pool leading up to Mexico City is amazing. She was also named sa���ʴ�ý’s athlete of the year at age 15, honoured with what is now called an Officer of the Order of sa���ʴ�ý medal at 18, and named to several swimming halls of fame.

Fifty-five years later, she is deemed by Ainsworth Sports, an athlete-ranking website, the fifth-best female Canadian swimmer of all time.

The journey began when her family moved from Vancouver to California.

High expectations

“I was five and I was a real fish,” Tanner said. “I loved to play in the water, and I’d watch Olympic swimmers train through the fence and pretend I was the world champion.”

She joined a competitive swim club and her coach was immediately impressed.

“My mom and dad never told me until I was a lot older — they didn’t want it to go to my head — but he told them I had Olympic potential.”

Despite being tiny, Tanner was a maniac in the water, she said, “graceful and powerful as a dolphin, but a fish out of water in social settings away from the pool.”

Against her wishes, the family moved to West Vancouver when she was eight. The first thing she did was join the Vancouver Dolphins’ swim club.

Howard Firby, founding coach of the Dolphins and a legend in Canadian swimming, took her under his wing. sa���ʴ�ý owes much of its swimming excellence to Firby, Swimming sa���ʴ�ý’s website says, calling the late coach one of the world’s top authorities on swim techniques.

Firby honed Tanner’s raw power and tenacity, turning her into a record-breaking swimmer with his understanding of kinetics, anatomy and, thanks to his visits to the Vancouver Aquarium to study how fish moved, aerodynamics.

“I listened to his every word,” Tanner said. “I just worshipped him, I still get goosebumps when I talk about him.”

Under his tutelage, a 15-year-old Tanner won four golds medals and three silvers and set two world records at the 1966 Commonwealth Games in Jamaica, a record medal haul at the time.

The following year in Winnipeg, Tanner won two Pan-Am Games gold medals, breaking two world records in the process, along with three silver medals.

“It was 1967, sa���ʴ�ý’s 100th birthday, I was doing the 200-metre backstroke, the last leg, and I remember the crowd started clapping and going wild because I had a chance to break the world record,” she said. “And the crowd brought me home.”

After she duplicated the feat in the 100-metre backstroke, the crowd erupted in a chorus of Bobby Gimby’s Centennial Song (Ca-Na-Da).

That’s when she began to feel the burden of keeping a nation happy.

“My special little dream that I’d kept in a box, of winning an Olympic gold, it was my little secret,” Tanner said. “Suddenly, it became everybody’s else’s dream, and all of a sudden you start looking at things differently.

“My job description now came with expectations.”

On top of expectations, Canadian Olympic officials threw a wrench into her preparations.

For one, the team moved to Banff to train for Mexico City’s high altitude, only to discover there was no Olympic-sized pool in the Alberta resort town (no one had thought to check).

“There we were with our swimming suits in our little bags and the Canadian Swimming Association said: ‘Oh, we need a pool.’”

They wound up in a place called the Cave and Basin, a rustic pavilion-style recreational hot springs.

“It was like trying to train in a hot tub,” Tanner said.

For another, Canadian Olympic officials wouldn’t let coach Firby, who had guided the 1964 Olympic team in Tokyo, be part of the team headed to the ’68 Games.

It was politics, Tanner said: “My coach had taken me from a little tadpole all the way to the top, and they wouldn’t let him near me.”

At the Olympics, team officials approached her just before the race to tell her to change her proven fast-start plan of attack, Tanner said.

They told her to start slowly, not realizing that in the lane next to her was Kaye Hall of the U.S., who heard every strategic word. Hall broke fast in the race and held on to win gold by a half-second in the 100-metre backstroke.

After that race, Tanner walked up to Canadian teammate Anne Walton.

“And I basically blanked,” she said. “I don’t remember who else I talked to. I don’t remember getting my medal.

“I don’t remember if I went to the presentation room with the reporters — some people said I did, some people said no, that I’d looked in the door and ran away. I don’t remember.”

‘The journey isn’t over’

Today’s young athletes have access to counselling and are taught PR skills. Yet many women still leave pro sports in their prime.

Tanner has concerns about the pressure faced by the current crop of young Canadian swimmers such as Summer McIntosh, who was 14 when she made her Olympic debut at the 2020 Tokyo Games. In 2017, Maclean’s magazine published Tanner’s open letter to teenage gold-medal-winner Penny Oleksiak.

“Sudden fame is a double-edged sword,” she cautioned.

During three hours of conversation about her life, tears were shed, but there was laughter as well.

The journey isn’t over, no journey ever really is, she said. But the hard part seems to be.

“There were no epiphanies, but with John’s help my healing truly began when I finally became honest with myself. Coming out of denial was the crucial first step to open up the pathway to wellness.

“I’ve learned life is about learning about yourself, being grateful, that when you’re going through a struggle there’s a lesson in the struggle. There is meaning in the things you struggle with, and in the end they become a conduit to your healing.

“The things we most struggle with can be the greatest gifts. Build yourself from the inside out, that’s my lesson in life.”