Eileen Delehanty Pearkes is a writer who explores landscape and the human imagination, with a focus on the history of the upper Columbia River and its tributaries. Born in the United States, educated at Stanford University (BA, English) and the University of British Columbia (MA, English), Eileen has been a resident of sa���ʴ�ý since 1985. She writes two popular columns on Canadian landscape history for The North Columbia Monthly and the online news website The Nelson Daily. In 2014, she curated an extensive exhibit on the history of the Upper Columbia River system in sa���ʴ�ý for the Touchstones Nelson museum and the Columbia Basin Trust, with specific reference to dramatic ecological changes both before and after the Columbia River Treaty (1961-64), as well as a history of the government policy that shaped this international water treaty. The exhibition won an award of excellence from the Canadian Museum Association. She lives in Nelson. The following is an excerpt from her most recent book, A River Captured: The Columbia River Treaty and Catastrophic Change.

��

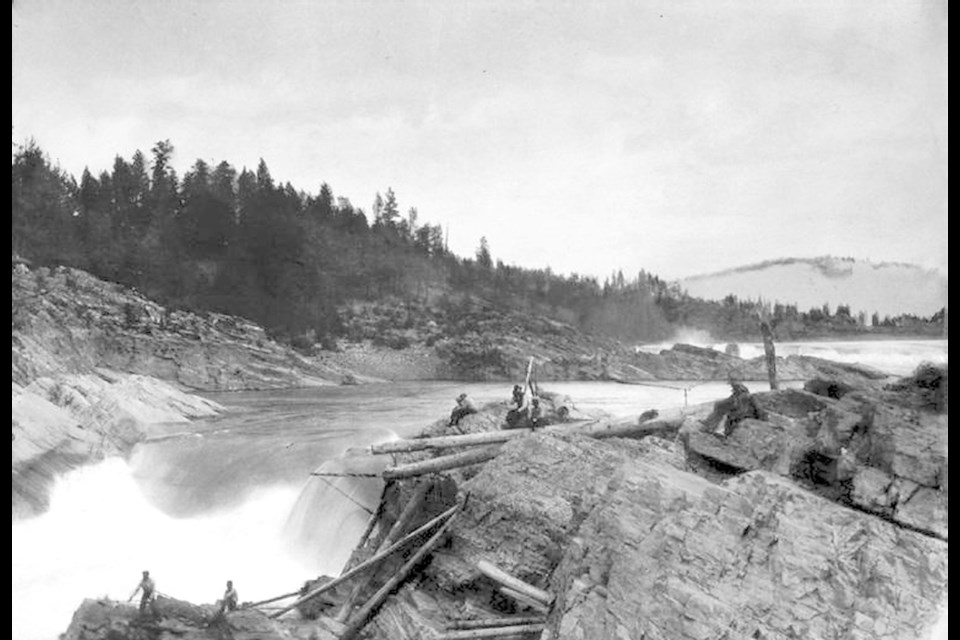

The mountain landscape of the upper Columbia River basin brims with the power of flowing water. Water burbles, roars, pools and turns. It transports minerals from high mountaintops to valley floors. It washes nutrients into flood plains. It carries fallen trees like matchsticks. It rolls boulders and scrubs gravels clean. The water cycle begins in winter, with abundant snow that forms mountains of its own, in drifts that soften the granite spires and glisten in the sharp sun during the coldest season. In spring, hundreds and thousands of seasonal and year-round streams go to work, draining their liquid charge down the rocky flanks, transporting newly melted snow to the valley bottoms. The transfer of energy that fills the air during the mountain-melt season is at once effortless and astonishing.

By early summer, the melt has subsided. By midsummer, most of the seasonal streams have gone bone dry. The year-round creeks are sighing rather than roaring. The quiet rhythms of water storage settle in.

When did I notice the reservoirs? I can’t really say. A handful of years after I arrived in the region, I looked beneath the surface of the striking beauty and abundant water of the upper Columbia River watershed. What I found surprised me: I live in one of the most intensively developed hydro-power regions in North America. The use of water for electricity has a long history, with one of the earliest hydro-power generators on the continent constructed here in the 1890s. Today, more than a dozen major dams and generating stations store and convert water’s natural power into electricity, providing 50 per cent of the power used in the entire province of sa���ʴ�ý Several dams date to the first great period of hydroelectric development in North America, between 1890 and 1930, when private, corporate interests developed the lower Kootenay River west of Nelson. But the biggest projects — and the most ecologically damaging ones — were constructed between 1964 and 1984 by the sa���ʴ�ý government, under the auspices of an international agreement with the United States: the Columbia River Treaty. Dams and the treaty are woven tightly into the fibres of our regional identity.

The upper Columbia watershed gives birth to the fourth-largest river in North America. This unique interior rainforest is a womb for abundant winter snow and copious rain in the shoulder seasons. The rest of the Columbia’s vast watershed terrain — to the south and west, stretching into the United States — is equally commanding in its variety and scope. The great river links the west slope of the Continental Divide with the Pacific Ocean, encompassing portions of seven U.S. states and British Columbia, and forming a land mass roughly equal to the size of France. Its watershed also contains a dizzying array of ecosystem types — from desert to rainforest — and hosts a myriad of tributary rivers of various sizes, lengths and power of their own. The American portion of the river’s 2,000-kilometre run is, like its Canadian cousin, also intensively developed for hydroelectricity. But it is the Canadian portion that is wettest and most alive with the water that gives the Columbia basin its power. North of the international boundary, this 15 per cent of the entire watershed provides up to 40 per cent of the Columbia’s international water volume. In dry years, that share can climb to 50��per cent.

Since 1964, the Columbia River Treaty has tightly governed the upper Columbia watershed’s river management, with sa���ʴ�ý annually providing 15.5��million acre-feet of stored snowmelt. The reasons for this storage are twofold: 1) to make greater, more efficient use of the annual surge of water in creating year-round electricity; and 2) to protect urban and agricultural communities from the annual flooding that is a natural component of a snow-charged system.

��

The Columbia River Treaty has long been hailed as a model of co-operation between two countries, and to a certain extent that has been true. For several decades now, the treaty has been peacefully implemented by a trans-boundary Permanent Engineering Board that has been remarkably collegial. The treaty’s in-built principle of sharing downstream power benefits between both countries has resulted in both benefiting economically from the hydro-power efficiencies. This shared economic benefit is a principle of fairness built into the life of the treaty, expressed by what is��also known as the Canadian Entitlement.

The Canadian Entitlement lies at the heart of the catastrophic ecological and social change caused by the Columbia River Treaty in sa���ʴ�ý. As this look at treaty history will demonstrate, sa���ʴ�ý’s interest in maximizing the initial monetary benefits of the Canadian Entitlement influenced the design of the system ultimately chosen by the two countries. The Columbia River Treaty’s power-producing principles — including the Canadian Entitlement — will continue in perpetuity unless there is a mutual agreement to make changes. If one side wants to terminate the treaty, it must give 10��years’ notice, and even then certain provisions would continue after termination.

On the surface, all is well and all will continue to be well for infinite peaceful co-operation between the two countries. But there is always something going on beneath the surface of any body of water. Including, and perhaps most especially, beneath reservoirs.

The second of the two main principles of the treaty’s management, flood control, will change. In 1964, the U.S. paid sa���ʴ�ý $64.4��million US to protect mostly American urban and agricultural communities from spring flood for 60 years, up to Sept. 16, 2024. After that period, the treaty dictates, the U.S. must first call upon its own reservoir system to provide the flood control it needs, before asking sa���ʴ�ý to use its reservoirs in the upper Columbia region for that purpose. It is the finite, 60-year flood control provision in the treaty that has opened the eyes of many people to potential changes in the entire treaty structure. Lots of people are talking about the river now: government officials, water-policy experts, academics, engineers and tribal and First Nations leaders on both sides of the boundary, as well as many other residents of the upper Columbia region. The voices of residents — of those whose lives were transformed by the advent of the CRT storage system — form the heart of this story of a river captured.

I had already been following the CRT’s history across the upper Columbia landscape for several years before I noticed that the water’s calm, controlled surface was being agitated by the possibility of renegotiation. As a cultural historian deeply interested in landscape, I grew even more curious about the system of dams and why they existed.

At times, as I studied the history of how the treaty came to be, I felt immersed in an uncontrolled stream swollen by spring snowmelt. I clutched at imagined shoreline branches or exposed roots, trying not to get pulled under by the treaty’s serpentine policy details, by its political secrets or by its uncomfortable truths. I will admit to nearly drowning myself in engineering reports, economic valuations, maps of transmission lines, old photos of farms flooded into reservoirs, and headlines filled with a spirit of congratulations about the treaty at last being ratified, or with the careful posturing of government leaders.

I will also admit that I wondered all along why I even wanted to know.

History tells two stories of the Columbia River Treaty. One of a model international agreement of co-operation and mutual advantage between two countries. Another, beneath the surface or largely forgotten, of an ecosystem and a way of life upended by corporate greed and betrayal. The widely praised national and international benefits of CRT water impoundment do not extend to the region that provides them. The landscape is a handmaiden for the whole system of dams, profitable hydro generation and copious irrigation supply.

The development of water resources in the upper Columbia region offers some universal truths about the North American settler culture. It is not the first story of modern humanity’s often paradoxical relationship with the natural world and its resources, nor am I idealistic enough to assume it will be the last. We live in a time when prosperity seems all too dependent upon use and abuse of the resources we hold as a common good.

As I journeyed from one corner of the upper Columbia basin to another, I learned to ask three questions: What has changed in the landscape where I live, who changed it, and why?

Wherever you live, I encourage you to do the same. In the answers to these questions may well lie the key to our future.

Excerpted from A River Captured: The Columbia River Treaty and��Catastrophic Change ©��Eileen��Delehanty Pearkes, 2016, Rocky��Mountain Books.