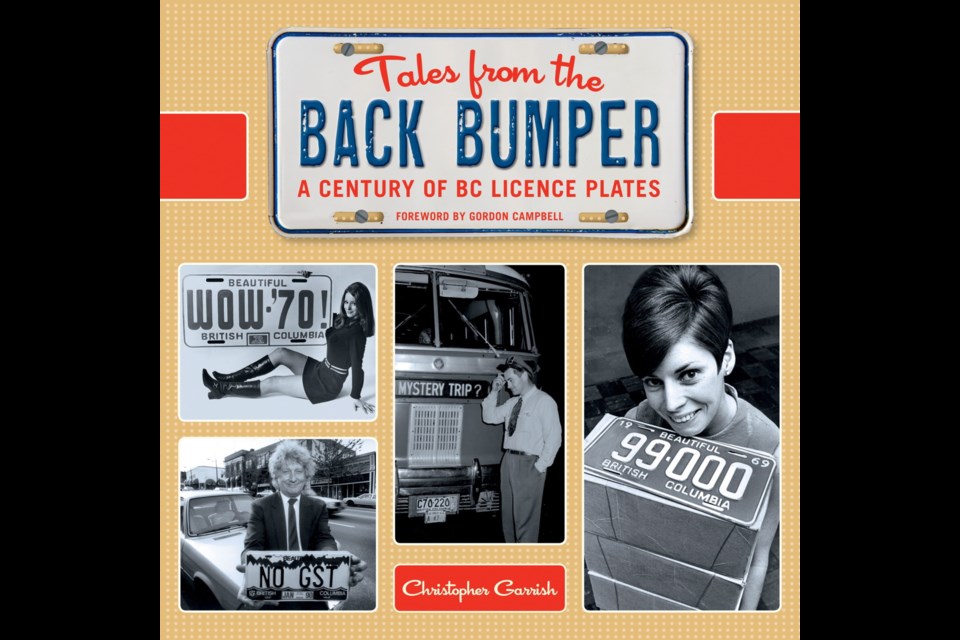

Penticton author and licence-plate collector Chris Garrish spent 12 years compiling Tales from the Back Bumper: A Century of sa���ʴ�ý Licence Plates, an account of sa���ʴ�ý history told from the perspective of the province’s licence plates. The result is a fun, nostalgic and highly informative ride through sa���ʴ�ý’s transportation history. In the excerpt below, the superintendent of provincial police, based in Bastion Square, grapples with how to enforce a new vehicle-registration law that requires drivers to fashion their own licence plates out of whatever materials are at hand.

For the first half-dozen years of the 20th century, the automobile was very much an oddity in British Columbia, and its future seemed uncertain.

A Vancouver engineering firm had an early version of a truck that could haul machinery down to the docks. The local roads, however, were so rough that the vehicle “shook to bits” and was abandoned.

In 1899, the Vancouver firm of Armstrong, Morrison & Company imported a Stanley Steamer car and planned to reproduce it in its shops and sell versions to the local market. But before production could begin, the shops were sold and the new owners chose not to pursue automobile manufacturing.

It would be another three years before the first automobile arrived on Vancouver Island: Dr. E.C. Hart imported a single-cylinder Oldsmobile on May 24, 1902, at a cost of $900 (the equivalent of roughly $24,000 today). After the vehicle was unloaded from a crate at the E&N station in Victoria, Hart proceeded to drive up Johnson Street, which was “tough going because crowds of people ranged in front and gawked as they had never seen anything like it.”

A few years later, the public mood shifted from fascination to annoyance, and the provincial legislature felt compelled to pass the first Act to Regulate the Speed and Operation of Motor Vehicles on Highways in 1904, even though there were no more than 32 vehicles in sa���ʴ�ý that year.

As automobiles became more popular across North America, accidents and mayhem followed in their wake. One story that circulated in the U.S. held that when the number of automobiles in Missouri numbered only four, two of them managed to collide on a St. Louis street with such force that both drivers were injured. In sa���ʴ�ý, the new legislation attempted to address some of these concerns by requiring basic safety equipment, such as warning signals, lights and a speed limit of 10 miles per hour in cities and 15 miles per hour in rural areas.

The superintendent of provincial police was in charge of ensuring that drivers were following the new speed limits and other regulations. This meant that motorists had to register their automobiles with the superintendent’s office and, in return, he would issue them a number and record their details in an official register. At the time, the Victoria office of the provincial police was located in the basement office of the courthouse in Bastion Square at Langley Street.

In order to register vehicles in the Victoria area, a constable would take the register, stand on Langley Street, stop each automobile that came along and inquire if the driver had paid for his licence. If the driver responded “no,” the officer would request the $2 fee on the spot and write out a receipt. The receipt number became the automobile’s registration number, and the driver was expected to have this number made into a single licence plate that would be displayed on the back of the vehicle.

The new legislation set out a few basic requirements for licence plates, but motorists were free to use any material that they wished. Joseph Morris, who had the first registration number in Alberta, opted to display the number by vertically attaching a broom handle on the rear of his vehicle. Local authorities tried to prosecute him for the improper display of a licence plate, but he was able to convince the presiding judge that the broom handle met the requirements of Alberta’s Automobile Act.

While British Columbia motorists from this period were not quite as inventive, they did make licence plates out of wood (planks, not broomsticks), canvas, metal and, most commonly, leather. A rectangular piece of leather could easily be obtained from the local horse stable, and house numbers and letters could be purchased from the corner hardware store.

One of the problems in allowing people to produce their own plates, apart from the lack of uniformity in design, was that the plates displayed no expiration date. A homemade licence plate could conceivably be used for years without any way for the police to easily identify a valid registration — which also made the identification of “blacklisted” drivers extremely difficult in an era before drivers were licensed.

With the number of registered vehicles nearing 4,250, the Motor Traffic Regulation Act (1911) was amended, and responsibility for the production and distribution of licence plates was transferred to the province effective March 1, 1913. From that point on, plates would be issued annually, display different colours than the year before, include an expiry date and be mounted on both the front and rear of a vehicle. These new regulations would allow the provincial police to keep better track of the number of vehicles being registered and make it difficult for people to shirk their registration fees, which had been increased to $10 for all vehicles.

Excerpted from Tales from the Back Bumper: A Century of sa���ʴ�ý Licence Plates. Heritage House Publishing © 2013 Christopher Garrish. With a foreword by Gordon Campbell.