It wasn’t so long ago that book publishers and bookstore owners were quailing about the coming of ebooks, like movie-theatre owners at the dawn of the television age.

Now they’re taking things more calmly. Recent statistics confirm a trend first noticed by the book trade in late 2015: At least among major publishers, ebook sales have plateaued or even begun to decline. It turns out that not all readers are quite ready to give up the tactile pleasures of holding a hardcover or paperback in their hands in order to partake of the convenience and digital features of ereading.

Here are the signposts: Ebook sales for the first nine months of 2016 were down 18.7 per cent compared with the same period a year earlier, according to the Association of American Publishers. It was the only category of four — including hardcovers, paperbacks and audiobooks — to suffer a decline in the AAP survey, which covered 1,200 publishing companies. Ebooks’ share of the total market fell to 17.6 per cent from 21.7 per cent in that time frame.

Meanwhile, in 2016, sales of hardcovers outstripped ebooks for the first time in five years, according to NPD Bookscan. The NPD data fell short of measuring the entire ebook market, NPD representative David Walter says — it didn’t count self-published ebooks or those sold through only a single retail source, such as Amazon’s specialty ebooks.

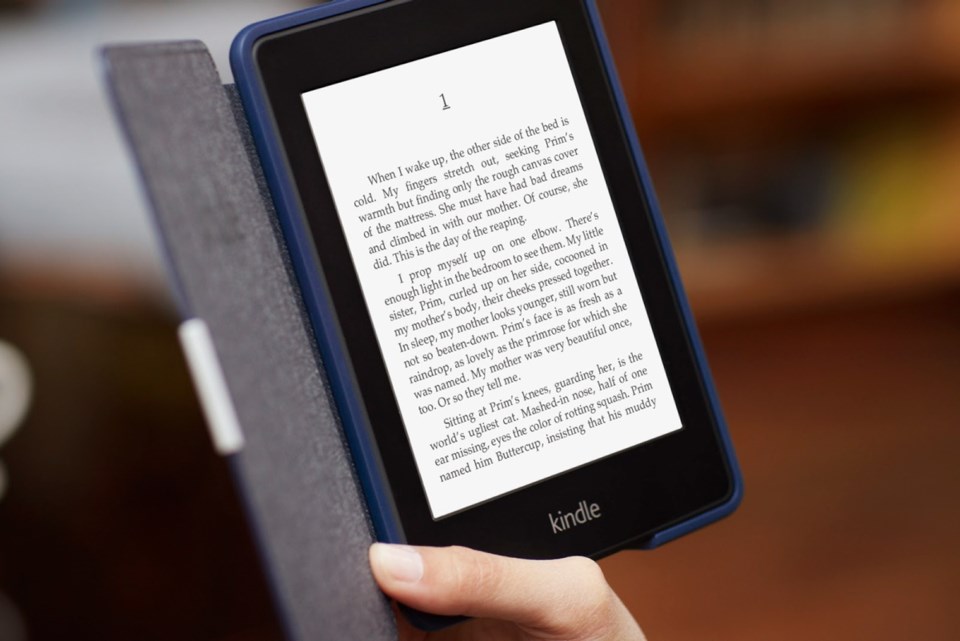

Finally, sales of dedicated ereaders such as Amazon Kindles appear to be on the decline; ownership of those devices fell to about 19 per cent of all U.S. adults in 2015 from more than 30 per cent in 2013, according to surveys by the Pew Research Center.

Yet ebook specialists say the overall market for digital reading is continuing to expand. “I won’t dispute that the Big Five publishers’ share of the ebook market is declining,” says Jeffrey Bruner, who distributes a newsletter of ebook recommendations via his website, thefussylibrarian.com. “But small presses and independent authors are taking a larger share.” The Big Five — Hachette, HarperCollins, Macmillan, Simon & Schuster, and Penguin Random House — account for 37 per cent of the overall book market, but only 26 per cent of all ebook sales.

The image of the ebook as a juggernaut has certainly taken a beating. “Five or six years ago, there was widespread panic that digital reading would take over our business,” said Oren Teicher, CEO of the American Booksellers Association. Physical books and ebooks might have reached a sort of equilibrium, he said. “The projection that it would be an either-or proposition has turned out not to be true. Customers who buy books are also reading digitally.”

What slowed the march of ebooks to world domination? Economics, technology and habit. (Disclosure: I do almost all my recreational reading on my beloved Kindle Voyage, but almost all of my professional reading in print.)

Several analysts point to ebook price increases imposed by major publishers in 2015, which brought the average price from $6 US to nearly $10. “Publishers wanted to establish a value proposition for print,” said Brian O’Leary, executive director of the Book Industry Study Group. That’s partially because marketers continue to use hardcover sales as guides to the commercial potential of their titles, and underpriced electronic versions were thought to be cutting into print sales. As the price gap narrowed, the relative allure of ebooks declined.

The fragmenting of the ereader market has blunted innovation in ebooks, O’Leary said. The latest industry specification for e-book formats, EPUB 3.1, accommodates interactivity and other digital features familiar from web browsers. But they’re incompatible with dedicated ereaders and even some smartphones and tablets. So publishers have little incentive to exploit those features.

Nor do device manufacturers have much incentive to meet the challenge. Amazon crushes the competition in ebooks and ereaders with more than 80 per cent of the English-language market, according to AuthorEarnings, a clearing house for industry data, so there may not be much it can gain by making its offerings more feature-rich. Its ebooks are compatible only with Kindles or computers, smartphones and tablets equipped with Amazon reading software.

Then there’s the cost of the reading device. Kindles range in price from $80 US for a no-frills version to $400 for its glitzy though underperforming Oasis, and its best device, the Voyage, costs a hefty $300. (Amazon plainly doesn’t believe in giving away the razor and making its money on blades.)

Those prices can pose a headwind for growth in the ebook market. “If you pay for a physical book, there’s no intervening device you have to buy to read it,” O’Leary says. As it happens, an increasing share of ebooks are read on tablets (50 per cent of ereading) and smartphones (about 18 per cent), with dedicated ereaders accounting for about 20 per cent. It’s also proper to point out that consumers of ebooks don’t technically own them — they’re just licensing them as software, which carries limitations on use that don’t exist with physical books.

Finally, there’s no getting away from the tangible delights of reading in a format that has remained essentially unchanged since the printer Aldus Manutius pioneered the portable, hand-held book — small enough to fit in a saddlebag — in 15th-century Venice.

Ereaders have their utility — my Kindle is filled with James Joyce’s Ulysses, the complete Sherlock Holmes and every novel by Charles Dickens and Joseph Conrad, yet weighs not a smidgen more than when it’s empty. But as the British novelist Anthony Powell entitled one of his classic novels of manners, Books Do Furnish a Room (available on Kindle for $6.72), what the publishing market has told us so far is that there’s room for the physical and the digital.