Pioneering sa╣·╝╩┤½├Į disc jockey Red┬ĀRobinson gives credit to rock┬ĀŌĆÖnŌĆÖ roll for the social move toward racial equality.

Robinson, 79, is a member of the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, inducted in 1995 in honour of the early air time and support he gave to the music. But he can still remember hate-filled phone calls when he was a DJ in Vancouver in the 1950s and early 1960s.

ŌĆ£I would get these phone calls asking: ŌĆśAre you that n----- lover?ŌĆÖŌĆØ he said in an interview in Victoria. ŌĆ£ŌĆśQuit playing that crap.ŌĆÖ ŌĆØ

ŌĆ£I guess playing it on the radio at that time was taking a risk,ŌĆØ said Robinson. ŌĆ£But when you are young, you donŌĆÖt think anybody can do anything to you or hurt you.ŌĆØ

ŌĆ£So we just kept on playing it,ŌĆØ he said. ŌĆ£And that music helped integration, there is no doubt in my mind.ŌĆØ

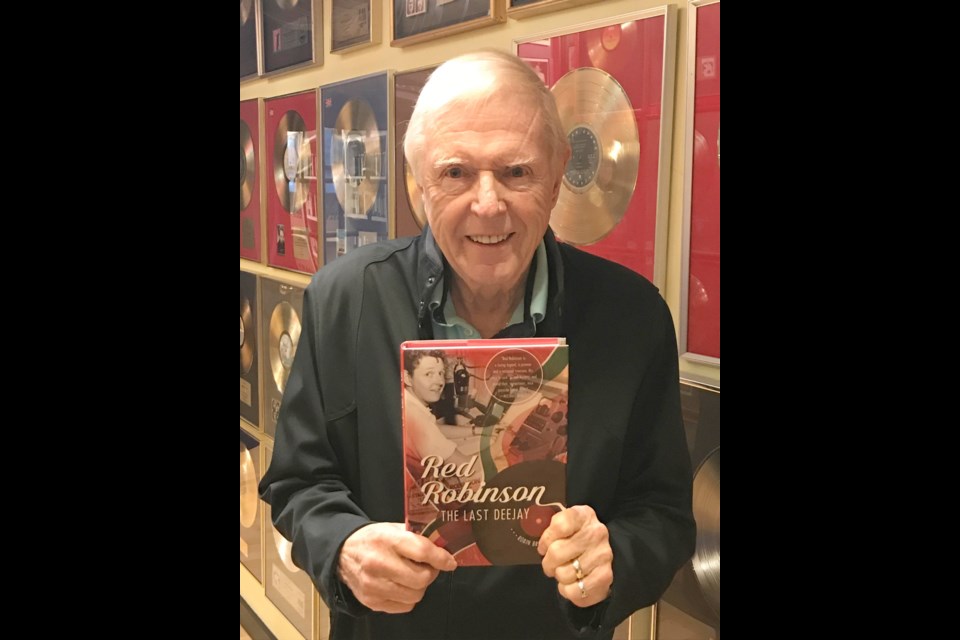

Robinson is the subject of a new biography The Last Deejay, which was published Saturday. It chronicles his encounters with early rock ŌĆÖnŌĆÖ roll, and rhythm and blues, first as Vancouver teenager, then an early DJ and later as a concert promoter.

He got to know the music and people of the African-American community. But the 1950s and early 1960s was a time when even buying the records of black artists was treated like something sinful.

ŌĆ£They would go under the counter and hand you the record, but only after they put it in a brown envelope,ŌĆØ said Robinson. ŌĆ£It was like buying pornography.ŌĆØ

Looking back, he also realizes he saw his DJ role as partly that of an educator, teaching people about the wonderful music of black artists and this electrifying new music called rock ŌĆÖnŌĆÖ roll.

So when he met artists such as Duke Ellington, he had to ask if they resented white artists covering their tunes. Mostly they didnŌĆÖt, as it meant segregationist walls were coming down.

Chuck Berry was surly, even nasty, but that was OK. Robinson thinks he had been cheated by so many record companies it had put a chip on his shoulder.

It was a time when DJs were expected to be public personalities who met, conversed and mingled with artists.

So when Little Richard was a guest on RobinsonŌĆÖs Vancouver radio show, it was arranged to have a piano in the studio so he could play Tutti Frutti on the air.

Same thing for Fats Domino. ŌĆ£Fats Domino, you just wanted to hug him, he was so lovable,ŌĆØ said Robinson.

He also got to meet the white artists behind early rock ŌĆÖnŌĆÖ roll and still has thousands of interviews on tape.

Buddy Holly told him on air in October 1953 he didnŌĆÖt think rock┬ĀŌĆÖnŌĆÖ roll would last much beyond Christmas.

Robinson spent six hours with Elvis Presley. But they talked about young-guy things, such as cars and young women, not music so much.

And he met the Beatles when he promoted their Vancouver concert in 1964. And on the advice of Beatles manager Brian Epstein, who was worried about the surging crowd, Robinson cancelled the show after 27 minutes.

ŌĆ£Brian Epstein asked me: ŌĆśHave you ever seen a British football match?ŌĆÖ ŌĆØ Robinson said. ŌĆ£ŌĆśNo? Well, people die.ŌĆÖ ŌĆØ

He is now at the age when early experiences are costing him his hearing, for which he has sought expert help in Victoria. The hearing loss has nothing to do with rock ŌĆÖnŌĆÖ roll, however. It was a stint in the army shooting a big gun.

Robinson still enjoys playing the old music even if he now gets a little impatient when he hears modern experts making people like John Lennon or Buddy Holly into visionary genuises.

ŌĆ£ItŌĆÖs important to remember they were all kids, and they just wanted to go out, have fun and play their music,ŌĆØ Robinson said.

ŌĆ£They were all dedicated to their music,ŌĆØ he said. ŌĆ£But we make way more out of them than they really were.ŌĆØ

ŌĆ£We were all just kids having a ball,ŌĆØ Robinson said.

Red Robinson, The Last Deejay is written by Robin Brunet and published by Harbour Publishing.