Karen McLaughlin’s pencil drawings are complex and detailed, inspired by nature, but apparently abstract in their patterning. The obsessive nature of her activity drew me in and I wanted to know more. When we met at the gallery, what I learned surprised and intrigued me.

Karen McLaughlin’s pencil drawings are complex and detailed, inspired by nature, but apparently abstract in their patterning. The obsessive nature of her activity drew me in and I wanted to know more. When we met at the gallery, what I learned surprised and intrigued me.

McLaughlin is a cheerful and well-spoken woman who told me she had led “a big life,” including blue-water sailing, living in locations all across sa���ʴ�ý, marriage and raising children. She went to art school when her kids were small and later wrote two published novels. As it turns out, McLaughlin has an “invisible disability,” trigeminal/glossopharyngeal neuralgia.

“I was 55 when it showed up,” she said.

She discovered that the cranial nerves at the back of her cerebellum were in conflict with her arteries there and, over the years, this invaded her consciousness. And now, it’s all about living with pain.

“Some days are better than others,” she said, “and there are lots of bad days.” At times she can’t speak or swallow very well, and suffers from facial spasms.

“Very awful,” she said.

McLaughlin has been successfully dealing with her problem by various means. Neurosurgery has played its part, and vital to her well-being has been training she has taken at the Victoria Pain Centre. Over the past two years, she took every class they offer, “some of them twice,” she smiled. Body-scan meditation quiets her nervous system, and she says that has given her back “a semblance of a normal life.”

Her problems surfaced during the years when she was living on Thetis Island, and at that time she poured her considerable energy and powers of concentration into drawing. Once, during a five-day power outage on the island, McLaughlin was arrested by an image she saw in her woodshed: “Chop — the axe goes down, the wood falls open, and there was a beautiful trail of bug tracks.”

In her married life McLaughlin told me, she had seen “the biggest things — huge construction sites in northern sa���ʴ�ý.” But by herself, on Thetis Island, she discovered that there was more happening in the world.

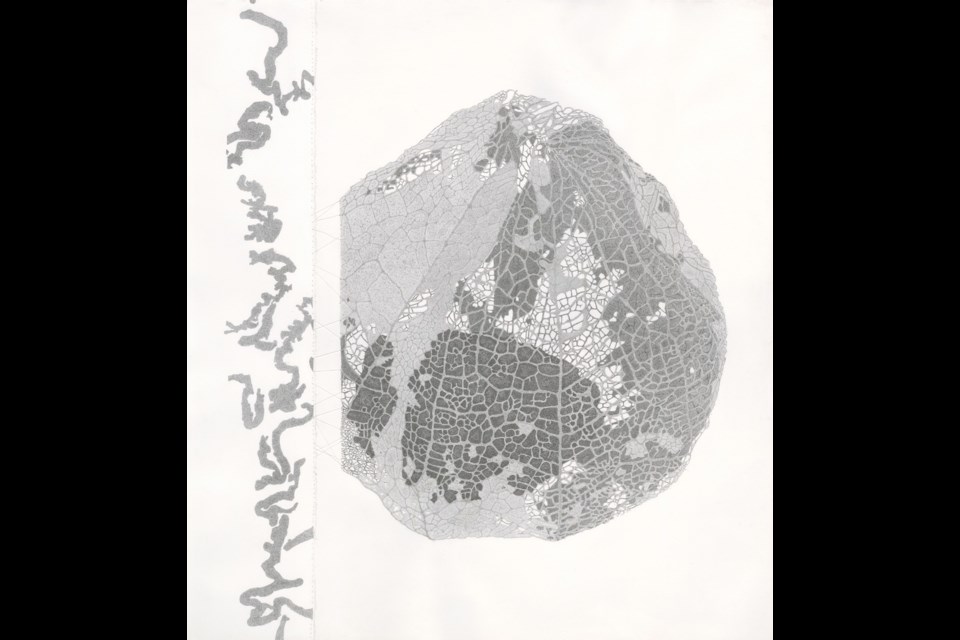

“What I’m interested in turned out to be the tiniest, tiniest things,” she said. She was captivated by the weathered skin of a tomatilla plant, which looked like lace after a winter outside. She took out a pencil and drew its three-dimensional network with profound concentration.

Besides her drawings, she has brought to the gallery many mugs full of pencils, sharpened down to a nub. Also at hand are magnifying glasses, encouraging a close look at her work. From a distance, the drawings sometimes seem hazy, but with magnification they are revealed as precise line drawings on a minute scale. No matter what the subject, she builds up its form from a field of tiny drawn marks, which under magnification have a texture like quinoa.

“I begin in the middle,” she told me. Her distinctive little curlicue pencil lines lead her on.

“I just keep attaching them. If I have to stop, when I begin again I find my tail and I just keep going.” She creates shading by adding layer upon layer of similar marks. “It’s evenly suspended intention … but it’s the same mark.

I picked up one of her pencils and was surprised by its extraordinary sharpness. Whether it’s a relatively soft 2B or a harder 2H pencil, she sharpens it using an electric sharpener and then a hand-operated “grinder.” In the end, she hones the needle point by whetting it on a sheet of paper. The hours and hours of mark-making that follow are her meditation.

McLaughlin’s imagery seems at a glance to be completely abstract, generated by the activity itself. But the artist informed me that her inspiration is drawn from small things in the organic world around her.

To make the point, she showed me slabs of wood with bits of the bark still in place. One day, in an inspired moment, she began jamming soft oil pastels into the wood’s textures, and eventually a richly coloured abstract pattern emerged. From her intimate conversation with natural forms, the results seem to reveal the forms of nature and also to express her own inner searches and struggles.

“When I first started,” she said, “I noticed that, after 20 minutes or half an hour, the very small things I focused on seemed to get big — my mind expanded. The image looked very large to me while I was working on it, and I could maybe hold that for a few hours.” It was an expanded sense of consciousness. The microcosm becomes the macrocosm: A small stone becomes a mountain range. “That became a new way of seeing the world around me. I began to see better, to draw more clearly. It was a space I never wanted to leave.”

With her return to something like health, McLaughlin has become a devoted student at the Vancouver Island School of Art.

“I love VISA,” she said. “I have found my new home. I lived alone for many years, but right now I’m happy to be surrounded by people.”

McLaughlin also credits the annual art exhibition for people with disabilities as the opportunity that brought her back out into the world as an artist. That’s where I discovered her work last year, and she will be one of the participants again this year, at Victoria Disability Resource Centre’s Fifth Annual Artists with Disabilities Showcase at the Art Gallery of Greater Victoria, Friday, Dec. 1 and Saturday, Dec. 2.

Critical Path: Karen McLaughlin’s Remarkable Art, until Nov. 30 at Martin Bachelor Gallery, 712 Cormorant St. 250-385-7919.