Jill Fitz Hirschbold is a photographer who likes to depict simple subjects (the prow of a boat; rust on a metal surface) in an abstract way, emphasizing theĚýformality of bold geometric compositions. She sometimes enhances the colours as the imagery passes from her camera to her computer, and then to the commercial printer who renders her imagery onto large stretched canvases.Ěý

Jill Fitz Hirschbold is a photographer who likes to depict simple subjects (the prow of a boat; rust on a metal surface) in an abstract way, emphasizing theĚýformality of bold geometric compositions. She sometimes enhances the colours as the imagery passes from her camera to her computer, and then to the commercial printer who renders her imagery onto large stretched canvases.Ěý

This way of creating images to hang on walls is becoming common in public exhibitions — Sooke, Sidney, and Victoria’s Look show —Ěý and mostly I don’t think of the result as “art” so much as “image capture.” Yet Hirschbold’s inventive design and vivid palette stopped me in my tracks when I came across them at the Brentwood Bay Inn, and I look forward to seeing them in a forthcoming show at Gage Gallery (2031 Oak Bay Avenue, 250-592-2760, gagegallery.ca, Nov. 29 - Jan. 7, 2017).

Ěý

Recently, Winchester Galleries showed some large photos printed on canvas. David Ellingsen concentrated on a human skull, its open cranium stuffed with remnants of other animals: antlers, femurs or seashells. He says that these images refer to the inception of the recently named Anthropocene Age, during which mankind has altered the living universe. He is a careful photographer, with a grand idea that he presents as colour photographs printed large. But does this grand concept elevate these photographic prints to the level of art?

It’s ironic that Winchester’s new show, which replaced Ellingsen’s, offers a dozen acrylic paintings on canvas by photorealist Tad Suzuki. Suzuki is a meticulous and very patient painter, whose evenly brushed acrylic paintings in reproduction are impossible to distinguish from his photographic source. That said, there is more to his artistry than simple “image capture.”

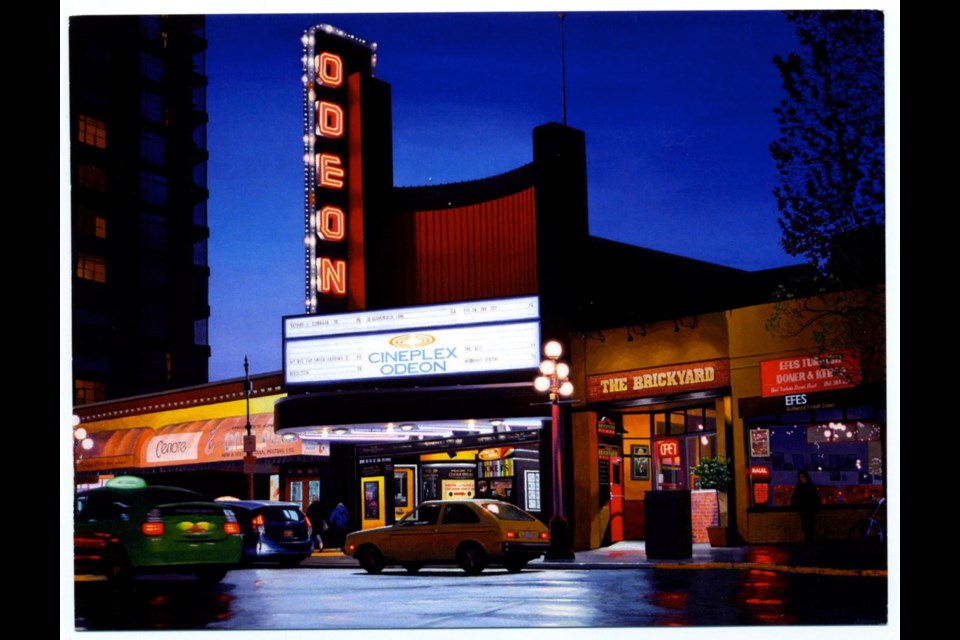

Suzuki chooses memorable subjects for his prolonged meditations. Standouts in this show are his renderings of Vancouver’s Stanley Theatre and Victoria’s Odeon on Yates Street, both seen at that “the violet hour” of twilight. He is a master of neon light, glowing lightbulbs and their reflections seen in car hoods and mirrored windows. And, when one looks closely at Suzuki’s paintings, as the artist himself does, one sees that his photorealism is assembled from myriad tiny abstract paintings.Ěý(Winchester Galleries, 2260ĚýOak Bay Ave., winchestergalleriesltd.com, 250-595-2777, until Nov. 26)

Ěý

The late Jim Gordaneer created thousands of paintings in many different modes. Polychrome Fine Arts is presenting a choice selection of his work focusing Ěýon railway steam locomotives. Though these paintings have never been displayed before, train engines were for him a compelling subject in his later years, offering fascinating three-dimensional forms to work with. Wheels, boilers, cowcatchers and smokestacks were imaginatively disassembled by the artist, then reassembled in cubist-inspired compositions full of brute energy and power.

The way Gordaneer played it, this imagery is generally recognizable, but the artist’s hand and thoughts always took precedence. Eschewing perspective, he forgedĚýa dense matrix from bits of these the iron-age behemoths. One can almost hear the crunching of freight cars assembling, and the squeal of steel wheels. Gordaneer abandoned the precise rendering of imagery in favour of a personal combination of reactions — another take on “realism.”ĚýĚý(Polychrome FineĚýArts, 977a Fort St., polychromefinearts.com, 250-382-2787, until Nov.Ěý17.)

Ěý

I once asked Glenn Howarth where he got his images, and he replied: “I have very precise hallucinations.” Howarth was a realist painter, committed to putting down scenes that had burned themselves into his eyes and mind. The images are always recognizable, but he left things open to the free play of his imagination, memory and dreams: the subconscious in general. This liminal openness he termed the “eidetic,” and it is pervasive in his work. Beyond his central subject, the indistinct images float in the out-of-focus margins of the canvas, and are some of the most interesting aspects of his art.

Howarth was a fixture on the Fan Tan Alley art scene from about 1978 until he moved to Brentwood Bay 25 years later. His work was recently seen at Uvic’s Library, in a show drawn from the trove of paintings given by the estate of Michael Williams to the University Art Collections, as well as Howarth’s papers, which have recently been provided by his family to the UVic Library’s Special Collections. Response to that show immediately spawned a second gathering that opened immediately upon the first show’s closing. Student/curator Jenelle Pasiechnik has brought out a new selection of Howarth’s large, round canvases from the Williams Collection. IĚýencourage all young painters to visit The Legacy Gallery — free admission! — to see what has already been accomplished here.Ěý

Ěý

Also at the Legacy is an exhibition of photographs of First Nations women, reclaiming their power and their sexuality. These are photographs as powerful documentary records. Each is a collaboration between Lindsay Delaronde, the photographer who proposed and pursued the idea, and the women who show and share transformative personal experiences. Their written commentary about these self-images is a vital part of the show. As a white man, my opinion is beside the point, but while I was there a group of women were moving through the gallery with notepads in hand. I could tell they were making contact with this show on a level far deeper than my own polite admiration. (Both Howarth and Delaronde on show at Legacy Art Gallery Downtown, 630 Yates St., 250-721-6562, legacy.uvic.ca, until Jan. 7, 2017).