Contemporary art by First Nations artists is the most important subject area in Canadian art. The three artists included in this show at Open Space ŌĆö lessLIE, Sonny Assu and Marianne Nicolson ŌĆö are young, talented and highly regarded nationally. And they all live on Vancouver Island.

Contemporary art by First Nations artists is the most important subject area in Canadian art. The three artists included in this show at Open Space ŌĆö lessLIE, Sonny Assu and Marianne Nicolson ŌĆö are young, talented and highly regarded nationally. And they all live on Vancouver Island.

Thoughtfully curated by France Tr├®panier and presented with assistance from the Royal British Columbia Museum, this is engagement with a powerful theme: Awakening Memory.

Awakening Memory is ŌĆ£a creative method for indigenous people to engage with objects that ŌĆśbelongŌĆÖ to them,ŌĆØ the curator has written. lessLIE is a Coast Salish artist of the Cowichan and Penelakut area, and a graduate of Malaspina University-College and later the University of Victoria. His paintings and prints, a regular feature at VictoriaŌĆÖs Alcheringa Gallery, tend to be simple ŌĆö almost minimalist. His writing is infused with humour and irony.

For this show, lessLie created a model of the fa├¦ade of the famous Butter Church near the mouth of the Cowichan River. This stone church was built by native people in 1870 following instructions from Catholic priests. But by 1880, the church was abandoned and has sat, haunted and derelict, for many years.

The artist discovered a Salish spindle whorl in the Royal British Columbia Museum, and made a sand-blasted glass replica, which he fitted into the ŌĆ£rose windowŌĆØ aperture in the fa├¦ade of the church. Once upon a time, the light shone out from within the church, but now light enters from outside through the spindle whorl and shines a light into this ruined church, a symbol of a legacy of abuse.

Sonny Assu is a LigwildaŌĆÖxw KwakwakaŌĆÖwakw contemporary artist, part of the celebrated Assu family of Quadra Island and Campbell River. Yet he grew up in Burnaby, another kid imbued with the colonial consumer culture. During his time studying art at Emily Carr University, Assu merged both his traditional and imposed backgrounds, and creatively imagined a world in which native culture had been allowed to grow without the dominant hand of the Indian Act.

His boxes of Treaty Flakes and Salmon Loops breakfast cereals, and his invitation to Olympic tourists to Enjoy Coast-Salish (rather than Coca-Cola) caught popular attention. A few years later, at the Art Gallery of Greater Victoria, he showed chunks of wood displayed like tribal masks. They proved to be offcuts of lumber, which coincidentally had human profiles.

Assu graduated from Emily Carr University in 2002 and was the schoolŌĆÖs Distinguished Alumni of 2006. His work has been purchased by the National Gallery of sa╣·╝╩┤½├Į and many others.

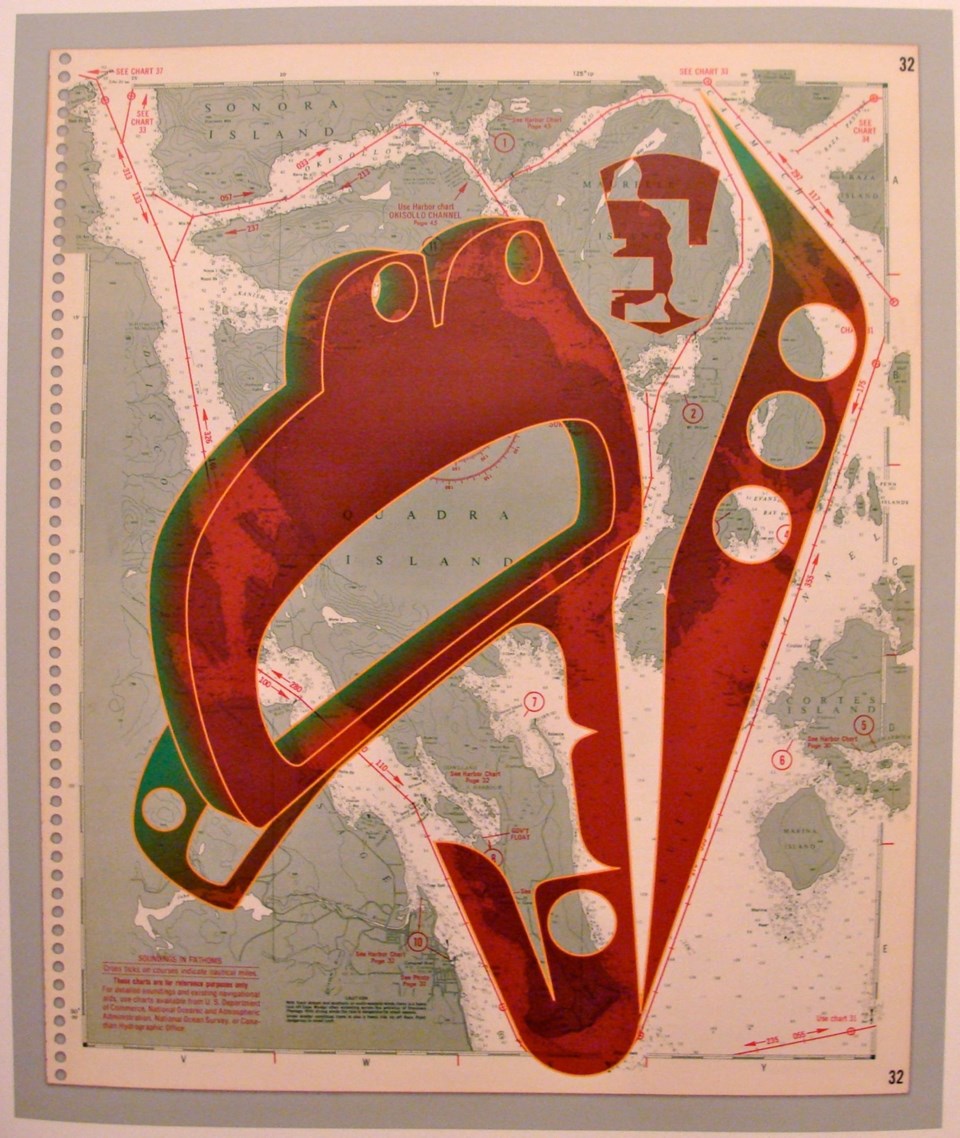

For the current show, he printed large versions of the coastal marine charts showing First Nations sites, an inheritance from a fisherman in his family. These charts are the very definition of a cultural overlay, redefining the world with all manner of rules and regulations: depth soundings, imposed names and notations to calculate magnetic declination.

Upon these maps, Assu has now reinstated the invisible native culture that still inhabits the land, sea and air: an awakening of memory. His network of formlines and totemic symbols add a strata of invisible power, returning a presence to the land that had been erased from the maps.

A closer look reveals that AssuŌĆÖs two-dimensional native designs have been given depth, as if carved out on a digital printer. Most prominent are shield-shaped ŌĆ£coppers,ŌĆØ the repositories of indigenous wealth. From these coppers, Assu has excavated the irregular shapes of reserves, land set aside by the Canadian government for native people.

Marianne Nicolson is a proud member of the DzawadaŌĆÖenuxw people of the KwakwakaŌĆÖwakw Nations. Nicolson holds a PhD in linguistics, anthropology and art history from University of Victoria (2013), and is an artist, speaker and writer on issues of aboriginal histories and politics arising from her passionate involvement in cultural revitalization and sustainability. Nicolson came to public notice with her immense painting of a copper on the cliffside wall at her home at Kingcome Inlet. ŌĆ£Marking the land,ŌĆØ she called it.

In her contribution to Awakening Memory, Nicolson makes sure we know that the land was not empty when the colonists arrived. Though it has suffered under an imposed governance system, the traditional engagement with and stewardship of the land by the KwakwakaŌĆÖwakw people has never ceased.

As an act of remembering, she made a video of a boat ride in the inlet with native elders, who in many ways make clear their connection to their home. Across from this large video projection, a splendid four-panel mural painting by Nicolson unfolds in a generous act of storytelling, presenting the DzawadaŌĆÖenuxw realities of this landscape.

Nicolson has prepared her panels with a sparkling slate colour to look something like rock. Then with red paint, she painted a rollicking scene of animals with a treasure box in a canoe. Closer inspection reveals waves and stars and everything in between. Even the imperial crown has a place. Inlaid into these panels are many mother-of-pearl buttons, set off by rows of military brass buttons. ItŌĆÖs a big story, here told from a local point of view.

Here are three artists with impressive credentials, putting their creative abilities in the service of our great national project of reconciliation. Living and working in our community, they have actively collaborated to inform, enlighten and entertain us.

To get a proper understanding of what theyŌĆÖre up to, itŌĆÖs important to watch the video at the entrance, which allows these eloquent artists to speak for themselves ŌĆö a vital introduction to this important and engaging exhibition.

Awakening Memory: a three-person show at Open Space (510 Fort St., 250-383-8833) until April 29.