Scientists from around the world are looking to the Saanich Inlet for clues about new ocean “dead zones.”

More than 20 researchers from saπ˙º ¥´√Ω and abroad are involved in a new project studying the inlet, which is a naturally occuring oxygen-minimum zone, or ‚Äúdead zone,‚Äù almost devoid of marine life.

The data could help scientists and policy-makers understand what to expect, as global temperatures rise and new dead zones appear around the globe, said Jeff Sorensen, a post-doctoral researcher at the University of Victoria.

“The reason we’re doing this big project is because these oxygen-minimum zones are expanding all over the world,” he said.

“We think of the Saanich Inlet as a natural lab.”

The Saanich Inlet is a deep glacial fjord. Its entrance is very shallow, which prevents water from mixing with the Strait of Georgia, except near the surface. The inlet’s deeper water stays where it is, Sorensen said.

“As it stays there, the things that live in the inlet — fish and critters — they consume oxygen from the water. And after a while, they consume all of the oxygen,” Sorensen said.

True dead zones are areas in the ocean devoid of oxygen and marine life, hosting only bacteria.

The dead zone occurs in the Saanich Inlet between January and September, until fall rains cause water to flow over its sill replenishing the oxygen supply and marine life returns.

It’s distinct from dead zones such as the one at the mouth of the Mississippi River, which is caused by excessive nutrients that rob the water of its oxygen.

The Saanich Inlet isn’t unique — the Black Sea hosts a dead zone on a much larger scale.

But the inlet’s proximity to research facilities means it’s often studied.

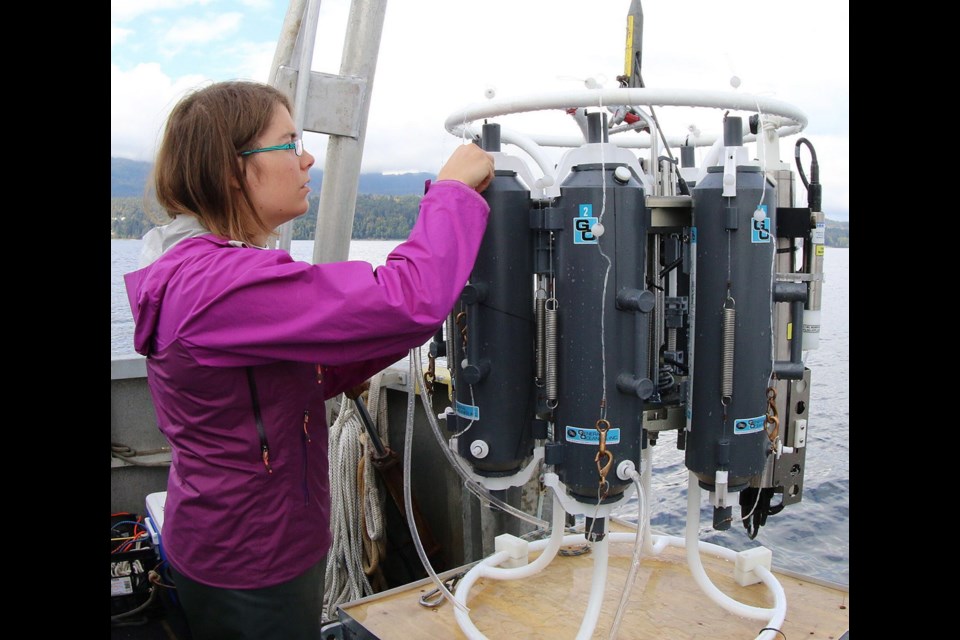

What’s different about this study is the frequency; it will create a record of conditions over the course of the cycle. Every two weeks since September, researchers have boarded the MSV John Strickland to collect about 300 litres of water samples per day. Samples are collected at various depths and measure everything from dissolved gases and trace metals to phytoplankton and microbes.

“Nobody has such a good picture over time. And what’s unique is the number of different things we’re measuring,” Sorensen said.

“When we have the data at the end, we’ll have a near-complete picture of what’s going on, as compared with a little snapshot, as we’ve had in the past.”

Collection crews are mostly local and include about 30 researchers from UVic, as well as scientists from Fisheries and Oceans saπ˙º ¥´√Ω and the University of British Columbia.

Twenty research groups from Switzerland, Ireland, England, Spain, Brazil, the U.S. and elsewhere in saπ˙º ¥´√Ω have signed on for water samples.

“People can look here, then look at their natural waters and say, ‘We have the same amount of oxygen they had in December.’ Then they can say, this is the chemistry, these are the types of biologies we see. And this is where we may be going in the future,” he said.

Dead zones are an expanding problem, Sorensen said. As ocean temperatures rise, the water can hold less oxygen.

“A major site where this is happening is the Mediterranean Sea. There are regions there that never had this issue previously, where the bottom water is starting to lose oxygen,” Sorensen said.

The consequences are far-reaching, impacts ranging from ecological to economic.

“Some of these regions are places where people fish and count on those fish for food or income. If that changes, it changes what kind of livelihood they can have.”