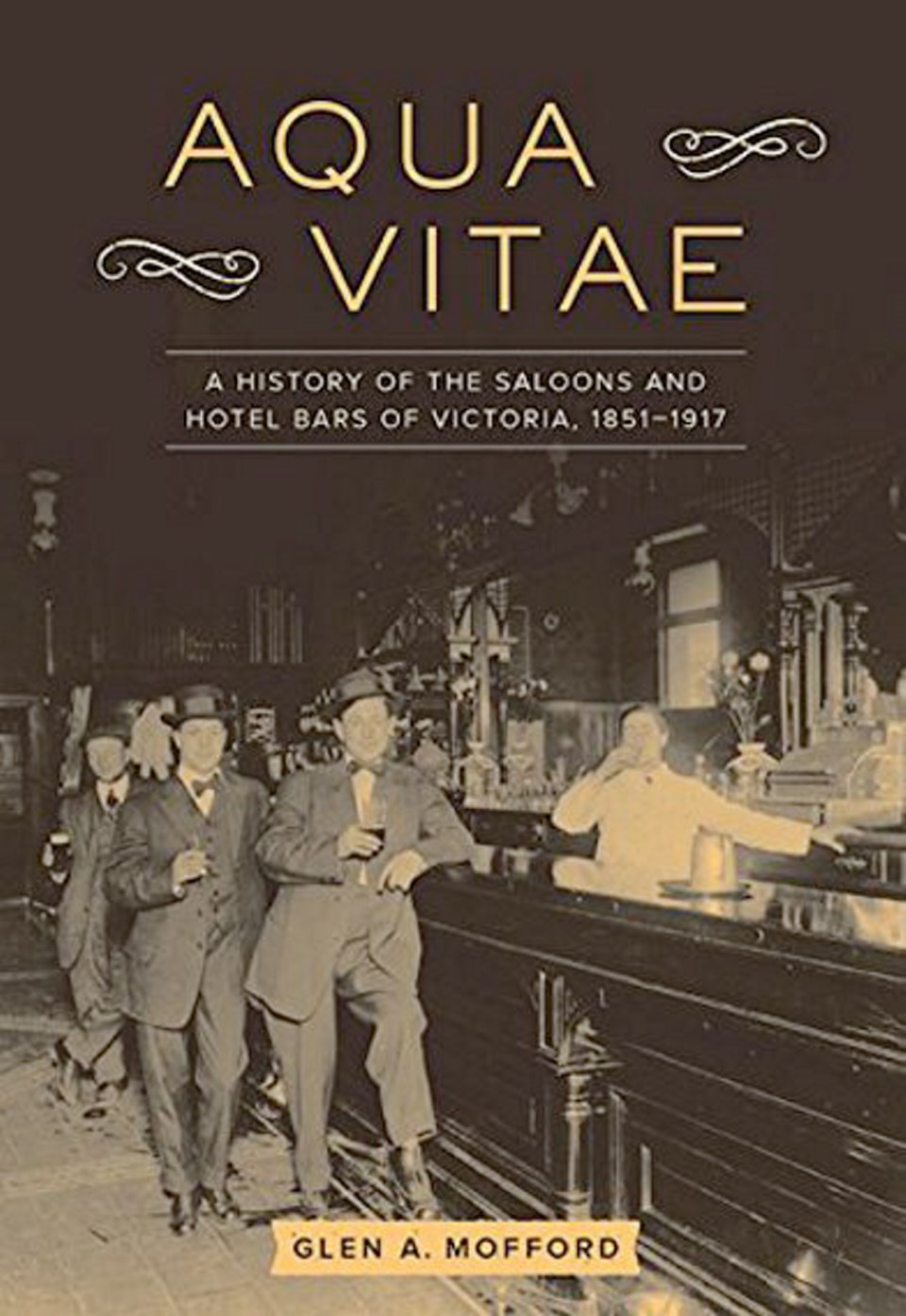

Aqua Vitae: A History of the Saloons and Hotel Bars of Victoria, 1851-1917

By Glen A. Mofford

Touchwood, 269 pp., $19.95

��

Watering holes have been a vital part of Victoria’s history for more than a century and a half. The first saloons opened before Victoria became a city, before British Columbia became a province, and before sa���ʴ�ý became a nation.

They were here even before this newspaper was founded, and that is saying something. Perhaps the presence of hard liquor helped drive the strong opinions that were as important as ink in the early days of Canadian journalism.

A history on drinking establishments is long overdue, and Glen A. Mofford has filled the need quite nicely, just as some of our ancestors filled the needs of the great, somewhat thirsty unwashed.

Aqua Vitae is Mofford’s first book, but he has been researching and writing about historic hotels and the imbibing opportunities they offered for more than a decade. As this book shows, Mofford is certainly qualified as an expert on the topic.

In the early days, drinking parlours were able to serve their thirsty patrons 24 hours a day, seven days a week.

Mofford takes us back to those times, and traces the history of saloons through the decades to the start of the First World War and the arrival of Prohibition.

He does not limit his work to the bars themselves. Mofford tells of the people who created them and the places they chose for them, as well as the business conditions that helped fuel the desire for alcohol products.

James Yates, a ship carpenter from Scotland who came to Victoria as an employee of the Hudson’s Bay Company, gets the credit for opening the first privately owned saloon in the city. He built it on two waterfront lots on Wharf Street, probably at the southeast corner of today’s Wharf and Yates streets.

He named his saloon the Ship Inn. In the years that followed, his business faced competition but survived, in no small part because Governor James Douglas introduced fees that drove the upstarts away.

Yates returned to Scotland a decade after opening his saloon. He had become a wealthy man, the first person to build a fortune selling liquor in Victoria. He left behind his name on a major thoroughfare and earned a place in this history book.

Over the years, many more saloons and bars were opened. They served a wide variety of patrons, from the rough-hewn to the elegant. There were watering holes for the working class, and there were more opulent places such as the Driard, which was considered to be the most luxurious hotel in North America in the late 1800s, as well as the Empress, which took the top honour from the Driard.

The glory days for saloons ended in 1913 when liquor regulation changes brought an end to bars that were not connected to hotels. The bars in hotels lasted four years after that, until their businesses were destroyed by Prohibition.

Prohibition worked in theory, but failed spectacularly in practice. By the time it was ended four years later, with liquor sales going under government control, more fortunes had been made — but this time, outside of the law.

Standalone bars returned to British Columbia 69 years after they were ordered closed, thanks to the neighbourhood pubs allowed by Dave Barrett’s New Democratic Party government.

Aqua Vitae is richly illustrated with photos, drawings and, best of all, maps. It is a comprehensive guide that is easy to read.

Beyond that, it is fascinating, dealing with a topic that has been ignored despite the impact that alcohol, and access to it, had on our ancestors.

The reviewer is the editor-in-chief of the sa���ʴ�ý.