NEW YORK, N.Y. - Cigarettes would have to be kept out of sight in New York City stores under a first-in-the-nation plan unveiled by Mayor Michael Bloomberg on Monday, igniting complaints from tobacco companies and smokers who said they've had enough with the city's crackdowns.

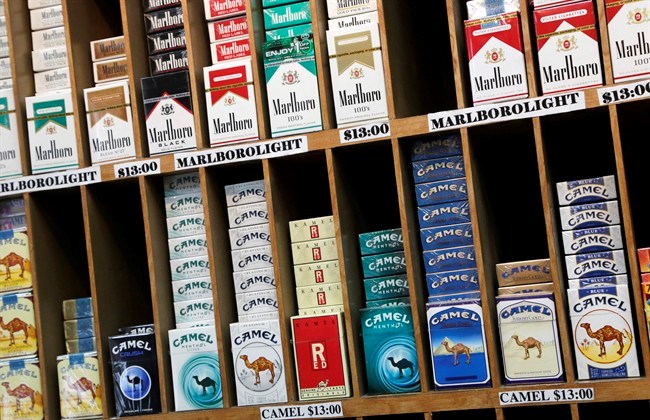

Shops from corner stores to supermarkets would have to keep tobacco products in cabinets, drawers, under the counter, behind a curtain or in other concealed spots. Officials also want to stop shops from taking cigarette coupons and honouring discounts, and are proposing a minimum price for cigarettes, though it's below what the going rate is in much of the city now.

Anti-smoking advocates and health experts hailed the proposals as a bold effort to take on a habit that remains the leading preventable cause of death in a city that already has helped impose the highest cigarette taxes in the country, barred smoking in restaurants, bars, parks and beaches and launched sometimes graphic advertising campaigns about the effects of smoking.

The ban on displaying cigarettes follows similar laws in Iceland, sa���ʴ�ý, England and Ireland, but it would be the first such measure in the U.S. It's aimed at discouraging young people from smoking.

"Such displays suggest that smoking is a normal activity," Bloomberg said. "And they invite young people to experiment with tobacco."

But smokers and cigarette sellers said the measure was overreaching.

"I don't disagree that smoking itself is risky, but it's a legal product," said Audrey Silk, who's affiliated with a smokers-rights group that has sued the city over previous regulations. "Tobacco's been normal for centuries. ... It's what he's doing that's not normal."

Slated to be introduced to the City Council on Wednesday, the anti-smoking proposal was also a sign that a mayor who has built a reputation as a public health crusader isn't backing off after a high-profile setback last week, when a judge struck down the city's novel effort to ban supersized, sugary drinks. The city is appealing that decision.

"We're doing these health things to save lives," Bloomberg said Monday.

Bloomberg, a billionaire who also has given $600 million of his own money to anti-smoking efforts around the world, began taking on tobacco use shortly after he became mayor in 2002. Adult smoking rates have since fallen by nearly a third — from 21.5 per cent in 2002 to 14.8 per cent in 2011, Health Commissioner Dr. Thomas Farley said.

But the youth rate has remained flat, at 8.5 per cent, since 2007. Some 28,000 city public high school students tried smoking for the first time in 2011, city officials say.

Keeping cigarettes under wraps could help change that, anti-smoking advocates say, citing studies that link exposure to smoking with starting it.

While some of the research focuses on cigarette advertising, a British study of 11-to-15-year-olds published last month in the journal Tobacco Control found that simply noticing tobacco products on display every time a youth visited a shop raised the odds he or she would at least try smoking by threefold, compared to peers who never noticed the products.

"What's exciting about this (New York City proposal) is that this is the most comprehensive set of tobacco-control regulations that affect stores or the retail outlets," said Kurt Ribisi, a professor of public health and cancer prevention specialist at the University of North Carolina. Moreover, cigarettes' visibility can trigger impulse buys by smokers who are trying to quit, he and city officials say.

The American Cancer Society Cancer Action Network, the American Lung Association, other anti-smoking groups and several City Council members applauded Bloomberg's announcement, made at a hospital in the borough of Queens. City Council Speaker Christine Quinn, who largely controls what goes to a vote, said through her office that she "supports the goal of these bills" but noted they would get a full review.

Measures in other countries have been coupled with bars on in-store advertising, but those nations have different legal standards around advertising and free speech. The New York proposal would still allow shops to display cigarette advertising and signs saying tobacco products were sold, raising the question of how effective it will be just to put the products under wraps.

But convenience store owners fear it could affect their business, by potentially leaving customers uncertain whether the shop carries their favourite brand and making them wait while a proprietor digs out a pack, said Jeff Lenard, a spokesman for the National Association of Convenience stores.

"It slows down the transaction, and our name is convenience stores," he said.

Jay Kim, who owns a Manhattan deli on 34th Street, saw the proposal as a bid to net fines.

"I know the city wants to collect money," he said at his store, where packs of cigarettes can be seen behind the counter, along with numerous signs warning of the dangers of smoking and prohibiting sales to minors.

Bloomberg, for his part, emphasized that collecting money was "not the reason."

The displays would be checked as part of the shops' normal city inspections; information on the potential penalties wasn't immediately available Monday night. Repeated violations of some of the other provisions, including the minimum-price and coupon ban, could get a store shuttered.

Stores that make more than half their revenue from tobacco products would be exempt from the display ban. Customers under 18, the legal age for buying cigarettes in New York, are barred from such stores without parents.

While the federal government regulates tobacco, states have some say in rules surrounding how it's sold.

Several of New York City's smoking regulations have survived court challenges. But a federal appeals court said last year that the city couldn't force tobacco retailers to display gruesome images of diseased lungs and decaying teeth. In that case, the court ruled that the federal government gets to decide how to warn people about the dangers of smoking.

The nation's largest tobacco company said the latest proposal also was too much.

"To the extent that this proposed law would ban the display of products to adult tobacco consumers, we believe it goes too far," said David Sutton, a spokesman for the Richmond, Virginia-based Altria Group Inc., parent company of Philip Morris USA, which makes the top-selling Marlboro brand. The company supported federal legislation that in 2009 gave the Food and Drug Administration the power to regulate tobacco products, which includes various retail restrictions, Sutton noted.

New York City smokers already face some of the highest cigarette prices in the country. With city and state taxes totalling $5.85 a pack, it's not uncommon for a pack to cost $13 or more in Manhattan. The proposed minimum price is $10.50, including taxes; city officials said it was aimed largely at clamping down on sales of smuggled and untaxed cigarettes.

Other public health measures Bloomberg has championed include pressuring restaurants to use less salt and add calorie counts to menus, and banning artificial trans fats from restaurant meals.

Jennifer Bailey, smoking as she waited for a bus on 34th Street, was no fan of the proposed tobacco restrictions or Bloomberg's other public health initiatives.

"It's like New York has become a ... dictatorship," she said.

___

Associated Press writers Deepti Hajela in New York and Michael Felberbaum in Richmond, Virginia, contributed to this report.