TORONTO - It's an accomplishment worthy of MacGyver.

Armed with only a mobile phone, some double-sided tape, a cheap ball lens and a flashlight, some doctors have jerry-rigged a microscope capable of diagnosing intestinal parasites in Tanzanian children.

"It's portable, it's relatively cheap, it's very easy to use. And it could be very useful in resource-poor settings that are remote or rural," says Dr. Isaac Bogoch, a Toronto General Hospital physician who is the lead author of the scientific article describing the effort.

Bogoch and colleagues from Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, the Swiss Tropical and Public Health Institute at the University of Basel, and the Pemba Public Health Laboratory in Tanzania field tested the device and reported their findings Monday in the American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene.

They had read in a medical journal that someone had made an iPhone microscope and tested it in a laboratory. But they wanted to know if such a tool could actually be used in the real world.

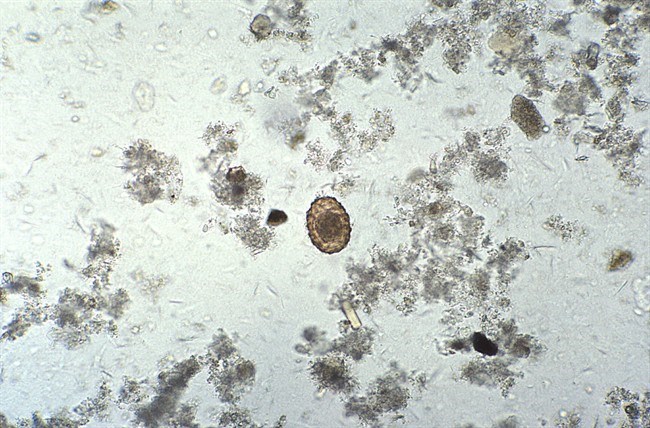

So they decided to see how an iPhone microscope stacked up against the real thing in a study they were running on Pemba Island, Tanzania. They were looking for common intestinal parasites in school children — infections with giant roundworms, roundworms and hookworms. It's estimated these types of worms infect about two billion people worldwide.

Infection rates can be particularly high in poor, remote regions of developing countries. Children afflicted by these worms can suffer from chronic anemia and malnutrition, which can stunt physical growth and mental development.

To look for the eggs that develop into these parasites, the scientists typically smear a small amount of stool on a glass slide, cover it with a second, and study the magnified image using a light microscope. Those cost about $200 and require electricity — which is not a constant in some settings.

So Bogoch and his colleagues affixed an $8 ball lens to the camera lens of an iPhone, using double-sided tape. They propped slides over a cheap flashlight and examined the magnified image with the adapted iPhone's camera.

"Our goal really was to use the simplest and cheapest options available," says Bogoch. "We really wanted to be as pragmatic as possible. Because ultimately, the goal is to use these products and use these devices in real world settings."

The results were pretty decent, though the researchers acknowledge more work needs to be done.

The phone's accuracy compared well to a real microscope with some of the parasites, but not so well for others. The results were best for parasites that produce a high density of eggs, or in people who were heavily infected. In other words, the more eggs per slide, the more likely the scientists could diagnose with the iPhone microscope.

But where there was a low density of eggs, the iPhone results didn't compare as well to the real microscope, catching only 14 per cent of hookworm cases, for instance.

For the roundworms and giant roundworms, the iPhone was successful at rates ranging from 44 per cent for light infections of roundworms to 93 per cent for moderate to heavy infections with giant roundworms.

The scientists estimate that if phone microscopes can be improved to the point where they are able to pick up about 80 per cent of infections they would be useful in the field. The initial study put the overall sensitivity at about 70 per cent.

"We're getting close. But it's not quite ready yet," Bogoch says. He says he and his colleagues will try again using a stronger ball lens.