GARY, Ind. - When medical students have finished their study and practice on cadavers, they often hold a respectful memorial service to honour these bodies donated to science.

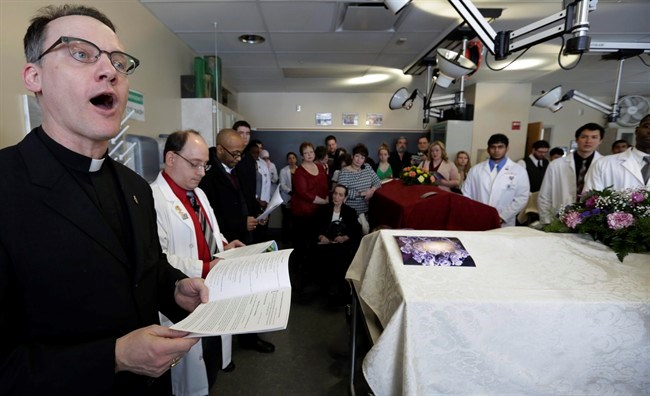

But the ceremonies at one medical school have a surreal twist: Relatives gather around the cold steel tables where their loved ones were dissected and which now hold their remains beneath metal covers. The tables are topped with white or burgundy-colored shrouds, flags for military veterans, flowers and candles.

The mixture of grace and goth at the Indiana University School of Medicine-Northwest campus might sound like a scene straight out filmmaker Tim Burton's quirky imagination. Yet, despite the surrounding shelves of medical specimens and cabinets of human bones, these dissection lab memorials are more moving than macabre.

The medical students join the families in the lab and read letters of appreciation about the donors, a clergy member offers prayers, and tears are shed.

Family members are often squeamish about entering that room. This year's ceremony was last Friday, and relatives of one of the six adult donors being honoured chose not to participate. And some who did attend had mixed feelings.

Joan Terry of Griffith, Ind., came to honour her sister, Judy Clemens, who died in 2011 at age 51 after a long battle with health problems including multiple sclerosis and osteoporosis. Terry said she felt a little hesitant about being in the dissection lab and was relieved that nothing too graphic was visible.

"I was kind of looking forward to coming," Terry said. "This is ... like a closure. I know Judy's not with us anymore. I know that she's dancing on the streets of gold in heaven. She's probably smiling knowing that her body's helping other people, helping these young doctors learn something about her, because that's what she wanted. That's the type of person that she was. She was always giving."

More than three dozen students, donors' relatives and campus staff members crowded the anatomy lab during Friday's memorial, surrounding the tables and standing solemnly along the room's perimeter. Some dabbed their eyes as prayers and remembrances were said, but faces were mostly stoic and there was no sobbing. The lab's usual odour of formaldehyde was strangely absent, masked perhaps by the sweet aroma of bouquets decorating the cadaver tables.

Some donors' relatives wore formal funeral attire. Terry, noting her plain pink T-shirt, said her sister wasn't a fancy person, either. Terry closed her eyes and struggled not to cry during the service, saying beforehand that Clemens "would be upset if I did."

Abdullah Malik, a medical student who worked on Judy Clemens, thanked her in a letter he read aloud during the ceremony.

"To have the courage and fortitude to endure as much as she did is a testament to her strength and an inspiration to us all," he read, standing next to Clemens' sister beside the dissection table holding Clemens' remains.

Ernest Talarico Jr., an assistant professor and director of anatomy coursework, created the unusual program and began holding the laboratory ceremonies in 2007. The cadavers are considered the medical students' first patients, and students are encouraged to have contact with the donors' families during the semester, too.

At other medical schools, donated bodies remain anonymous and students never meet the families. Talarico said his program humanizes the learning experience.

Talarico views the services as life-affirming and a chance to give thanks. The education these donated bodies have provided is invaluable, he says, teaching doctors-to-be how the body works, and what causes things to go wrong.

"We look at it as a celebration of the lives of those individuals and the gift that they have given to us," Talarico said.

He considers the location fitting.

"I think it is appropriate in that we honour them in the setting in which they desired to give what they viewed as their last gift to humanity," he said.

Malik, the medical student, said knowing the donors' identities and meeting their families enriches the students' medical education.

"Once you put a name and a face to the body that you're working with, once you kind of put an identity to it, you kind of connect to it in a really meaningful and powerful way," he said.

Medical student Kyle Parker said he admired the donors' relatives for showing up, and wondered if he were in their shoes, "would I be willing to meet the people who have actually dissected my family member?"

Parker said he hopes the answer would be yes.

___

Online:

Indiana University School of Medicine-Northwest: http://iusm-nw.medicine.iu.edu

___

AP Medical Writer Lindsey Tanner can be reached at: http://www.Twitter.com/LindseyTanner