TORONTO - Canadian researchers have used the power of genomics to identify the cause of a rare Parkinson's-like disease in children of one extended family and come up with a treatment to help reverse its effects.

It's believed to be the first time a new disease has been discovered, its cause figured out and a treatment successfully determined in such a short time, in this case about two years.

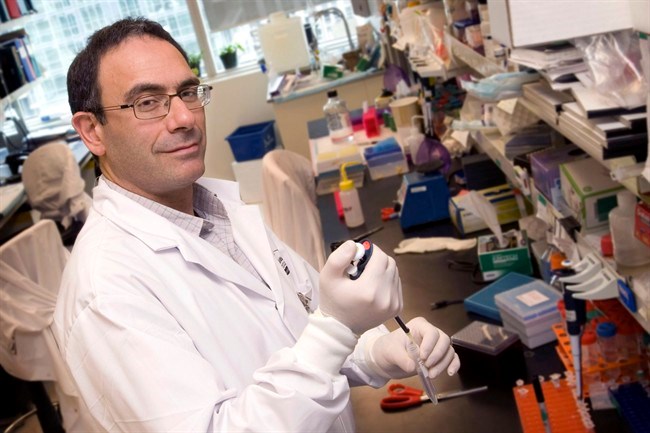

The eight children — five boys and three girls born to four sets of parents in a large Saudi Arabian family — were born with symptoms similar to those experienced by adults with Parkinson's disease, said principal researcher Dr. Berge Minassian, a neurologist at Toronto's Hospital for Sick Children.

"They're very interesting, they're like little babies with Parkinson's disease," said Minassian, explaining that the children exhibited typical symptoms of the neurological disorder, including tremors, problems executing movements, and the flat facial expression known as a "masked face."

"Those kids are like that. They cry, but you don't see them cry," he said.

Dr. Reem Alkhater, a pediatric neurology resident at the hospital, has been travelling back and forth between Toronto and Saudi Arabia as part of the research team's investigations into the familial disorder.

The children are part of an unidentified family of Bedouin ancestry living in a western Saudi city whose members had intermarried through several generations. Known as consanguineous marriages, the offspring of such unions have a one in four chance of inheriting mutated genes if they are carried by both parents.

"When you have consanguinity, then you end up with problems where you get the bad copy from each side because the two sides are related," said Minassian. "In this case, consanguinity played a role in these children being sick and having this autosomal recessive disease."

Using genomic sequencing, the Toronto scientists pinpointed a common mutated gene among the children, known as SLC18A2. (The genome is all the genetic material in a person or any other organism.)

The gene, which is involved in the production of the brain chemicals dopamine and serotonin, had a single genetic-letter misprint, which dramatically reduced its function and produced the Parkinson's-like disorder, he said.

Based on the symptoms, doctors treated one 16-year-old girl and three of her affected younger siblings with L-dopa, a drug that boosts dopamine in the brain. Classic Parkinson's is caused by diminished levels of the neurotransmitter, and L-dopa is one of the standard treatments.

"It made them worse, so we quickly stopped," he said.

The researchers then determined that despite the mutation, the children's bodies were making enough dopamine — it just wasn't getting "packaged" properly and delivered where it needed to go in the brain. In fact, in that state, it was toxic to brain cells.

The children were then treated with another standard drug called a dopamine agonist. "These are newer compounds that bypass the whole packaging thing and go directly to the dopamine receptors (on the surface of cells)," Minassian said.

"Now we are providing dopamine where it belongs without the need of packaging and so it made the patients better," he said.

Within days of starting the drug, the children began improving, although those who were older did not do as well as the younger kids, say the researchers, who detail their work in Wednesday's issue of the New England Journal of Medicine.

"If we treated them very young, they responded almost completely," Minassian said.

"It was magical. These kids, it's like one day they're frozen and cannot move and they're just either sitting or lying, depending on their age, and as soon as we treated them, they get up and start running.

"And then they were so excited to walk and run, they wouldn't stop. So we had to put helmets on them because they were falling all over the place."

It's been almost three years since the children began receiving the drug, which they must take for life. Their symptoms continue to improve with minimal side-effects, primarily slight overactivity and weight loss, the authors report.

Their work is a good example of personalized medicine — medical care that is tailored to an individual's genetic profile, said Dr. Sylvia Stockler, head of the division of biochemical diseases at sa���ʴ�ý Children's Hospital.

"It's really a great article, so congratulations to the team in Sick Kids that they had such a successful story to report," she said of the study.

"It's really great work because we have so many children with unexplained, severe neurological handicaps and intellectual disability, where we just do not know where it comes from," Stockler said Wednesday from Vancouver.

Even knowing that such rare diseases must have a genetic basis — and having high-tech genomic-sequencing equipment to investigate — doesn't mean it's easy to narrow down the search for a faulty gene or a series of faulty genes, she said.

Stockler's own team has been trying, so far unsuccessfully, to pin down the genetic cause of similar rare neurological diseases in children that share some of the symptoms seen in the Saudi kids.

"We will probably go back and look right away into that gene," she said of SLC18A2.

"We have quite a list of patients where we think there might have been a new gene defect and this definitely will help us also in looking at the right spot in the genome of those patients."

Minassian said the team is "very excited" about helping the children and the speed at which they were able to pin down the cause of their disease. He attributes their success to new technology that allows scientists to sequence chunks of DNA much faster than in the past.

"So many diseases are either completely genetic or have big contributions from genetic mutations," he said. "And now we have technologies that get us directly to the causes by whole-genome sequencing.

"And so it's quite striking what can be done these days. A project like this would have taken 20 years, just a few years ago. But now it can all be done very quickly."