It was alumni night at the Keg on Quadra this week, a chance for former employees to wax nostalgic about the restaurant chain’s half century in Victoria.

As it turns out, plenty of well-known names have tied an apron at the Keg’s two local eateries.

Premier John Horgan was once a Keg waiter in Victoria. Jeff Mallett, the Mount Doug and UVic soccer player who went on to build Internet giant Yahoo and buy big chunks of the San Francisco Giants and Vancouver Whitecaps, started as a dishwasher.

Pamela Anderson worked at the Fort Street restaurant, first as a hostess, then as a server in its lounge. (“I used to wear prom dresses and sit behind the podium,” she once told the TC’s Michael D. Reid.) Keg lore says the waiters competed for Anderson’s attention, but she preferred to hang out with the cooks, leaving her signature among those on the wall of an old boiler room where chefs would retreat for a smoke. A few years later, she was arguably the best-known Canadian in the world.

Lesser local luminaries passed through, too. Future Oak Bay Mayor Chris Causton trained future Victoria city councillor Chris Coleman to be a server. Coleman actually worked at eight different Kegs over the years, first in Victoria, then the Lower Mainland while going to law school, then as a staff trainer.

He couldn’t help but notice that while the Keg clan (and they did feel like a clan) might have drawn heavily from university kids and rugby players like himself, there were also lots of Asian immigrants. They were the ones who stuck around. It was a symbiotic relationship, the restaurant giving the immigrants a toehold in sa���ʴ�ý, the newcomers providing the Keg with a base of solid employees.

How did that come about? In Victoria, co-franchisee Jason Frost says, it was a product of the city’s restaurant scene at the time. When the Keg came to town, there wasn’t a big inventory of trained staff waiting to be hired. “Restaurants were either family-owned, or in a hotel, or very high end,” Frost says. “The Keg had to go outside the box.”

The University of Victoria, particularly its jocks, was one answer. Immigrants, or at least a segment of them, comprised another. Some were actual refugees, boat people from Vietnam. They might not have reflected a bigger picture in which many of the era’s immigrants arrived in sa���ʴ�ý bound for grad school or equipped to transition into a successful life, but for some of those at the Keg the job meant more than just rent and tuition. It meant survival.

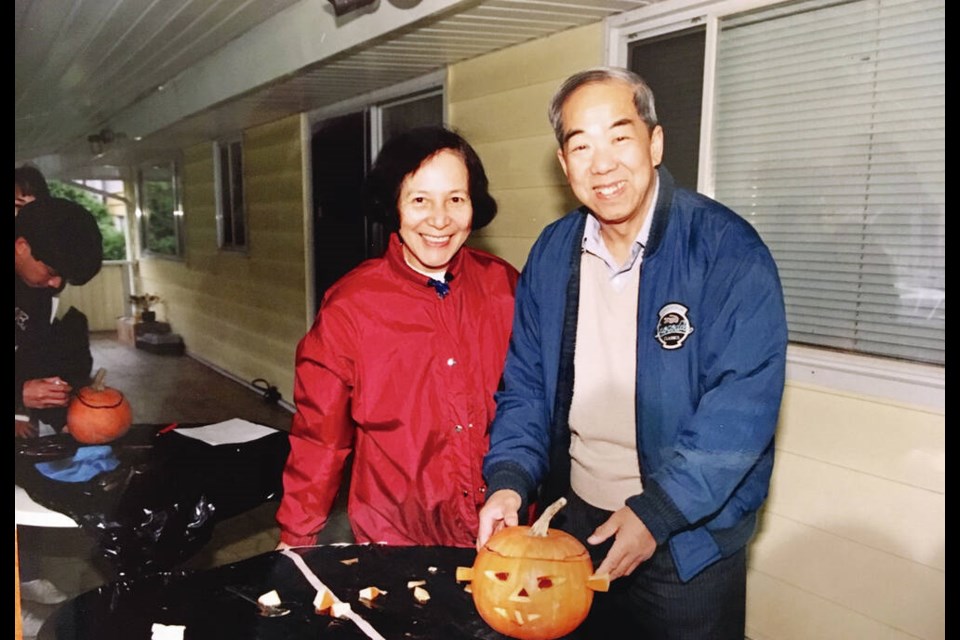

Not everyone was fleeing a bad situation. Don Poon had a comfortable life as part-owner of a plastics factory in Hong Kong, but with Red China (that’s what we called it then) preparing to take over the colony, he and his wife Sophia figured sa���ʴ�ý would offer their son and daughter a better education, a better future. The family moved to Victoria, where a relative lived, in 1974.

With little English, Victoria wasn’t easy, though. Don, the former factory owner, ended up washing dishes at the downtown Keg. Then he became janitor. Then a prep cook. When he left the janitor job, Sophia moved into that role. “They’d go to work together and go home together,” son Eric Poon recalls.

Then Eric got dragged down to the restaurant at age 13. “My dad didn’t want me hanging around the street in the summer.” Eric worked there until university. Coleman says he’s never seen prouder Canadians than Don and Sophia when their son graduated from UBC.

Looking back, Eric, now a commercial real estate agent on the Lower Mainland, reciprocates that pride. “They came over here for us. My dad had a pretty cushy job back home. He didn’t have to leave.”

“I look back now, and see he worked hard.”

Those were the days when a working wage would let you buy a house, which the Poons did, but theirs wasn’t a life with a lot of frills. Going out for Chinese food on the weekend was as wild as they got. After the kids moved to the Lower Mainland, their parents followed, Don getting a job at a Keg there. Both parents are gone now.

Their story isn’t uncommon in this country. Ours is a nation of immigrants. More than one in five Canadians were born elsewhere. Most of us had at least one parent or grandparent with an accent, from China, or Scotland, or India, or Ukraine, looking for a better life for their children.

>>> To comment on this article, write a letter to the editor: [email protected]