The mystery of the soldier’s diary has been solved — though not with a storybook ending.

Charles Deane Douglass, who graduated from school in Victoria, never made it home from the First World War. He was still a teenager when he died near Ypres, in Flanders, where the poppies grow.

This story began two weeks ago when a slim, pocket-sized diary emerged from one of the boxes of donations to the sa���ʴ�ý Book Sale.

Pencilled in cramped and now-faded letters by a private from Bassano, Alta., it chronicled life in the trenches in 1916 — gas attacks, no-blankets nights in the snow, unrelenting shell fire, a young man’s hand being blown off, death. Then, after a final entry in June, nothing but blank pages.

How did the diary arrive at a Victoria book sale, we wondered, and what happened to the author?

The answers arrived from multiple directions.

First to write was Sidney nurse Katy Dallen, who recognized the soldier as Deane Douglass. Her grandmother’s older brother, he was killed in action in July 1916.

Dallen sent a photo of her great-uncle’s grave in Belgium, which she had visited a few years ago, and a link to a story in the Vancouver Sun.

Next came an email from another Sidney woman, retired researcher Janice Owen, who had plunged into military and genealogical records after reading of the diary.

She discovered that Douglass, born in Alberta in 1896, worked as a surveyor before enlisting on Nov. 14, 1914, just weeks after turning 18.

He shipped out for England (aboard the RMS Carpathia, best known as the ship that rescued Titanic survivors) with the Canadian Expeditionary Force in May 1915.

Key to Owen’s findings was a PDF of an earlier Douglass diary, one covering the period from his arrival in France in September 1915 to the end of that year.

“The 1915 diary is about a young prairie boy who is, at least for a few days, on a great adventure, until it is not so great any more as he lives in water-filled trenches and army tents, inhales poisonous German gases, is shot at and survives his first 3½ months at the front,” she wrote.

Owen singled out a particularly touching entry in which the young soldier celebrated his 19th birthday (“Many Happy Returns of the day Deane Douglass, if you don’t have anybody else to wish it you might as well congratulate yourself…. Mud up to your neck”).

The 1915 diary had been posted online by Vancouver’s Michael Wale, the husband of Janice Hope, whose grandmother, like Dallen’s, was one of Douglass’ three sisters. Unaware of the existence of the 1916 diary, Wale emailed the sa���ʴ�ý last week after being tracked down by Owen.

It turned out Wale and Hope had found the 1915 diary after going through old family papers two years ago after the death of Hope’s father. It was Wale who forwarded his transcription of the diary to the Vancouver Sun, where John Mackie used it as the basis for a touching piece last Remembrance Day.

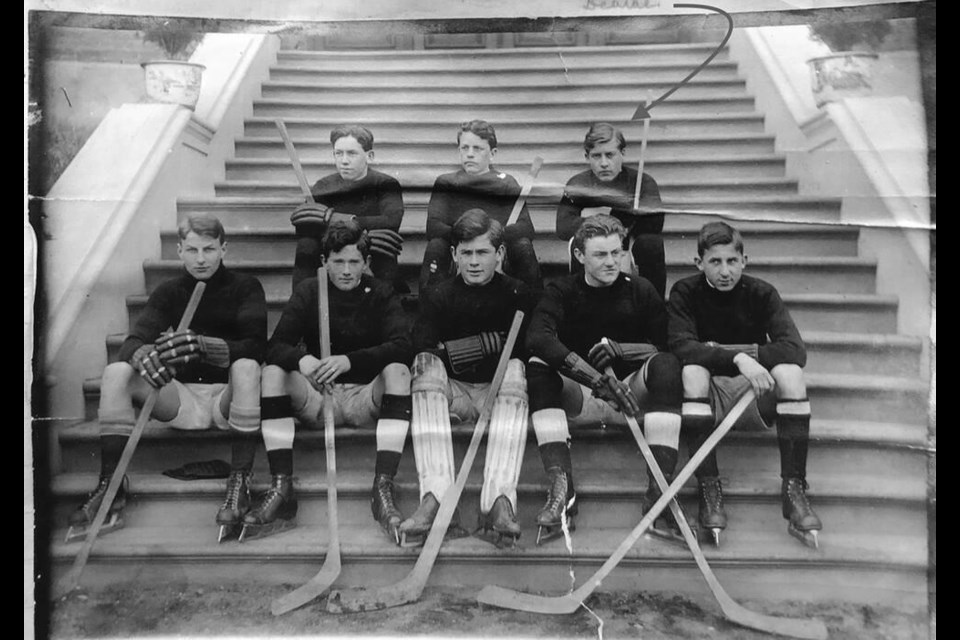

Wale also forwarded photos of Douglass, including one from his days on the hockey team at Victoria’s University School — a predecessor of the current St. Michaels University School — after the family moved to Vancouver Island.

How did the 1916 diary end up at the book sale? Wale thinks it was inadvertently included in a box of books donated by his wife’s brother, who lives in Victoria.

Both diaries are revealing.

Where Douglass’s letters home carried a cheerful tone, Wale says, the teenager’s diary entries told a grimmer, unfiltered truth.

That, Dallen says, is why diaries are so valuable. They reveal unvarnished, uncensored thoughts.

They also keep loved ones alive. Dallen remembers camping trips on which her grandmother and great-aunts spoke of their lost brother frequently. “I heard about Deane a lot.”

What must those siblings have thought while reading the diaries, their brother’s voice echoing from the battlefield?

“You get sort of used to rifle fire but those shells can sure bark,” Douglass wrote shortly after arriving in the trenches. He soon learned to differentiate between the types of incoming artillery — “whiz bangs” “sausages” and the ground-shaking concussion of “Jack Johnsons.”

“About 6 o’clock this evening they sent over some bombs of all descriptions,” read his Oct. 27, 1915 entry. “They are most demoralizing, one of them nearly got me. There were three of us in a bay when I saw a trench mortar coming straight for us. I tried to dodge but my equipment got hung up on a peg. I knew it was getting close then so just fell flat down and then what an explosion, blew a lot of the parapet away. Half burying us filling your eyes ears and mouth with mud, this was about all I remembered for a minute or two.”

Douglass got off lucky that time. Although deafened in one ear, he was otherwise unharmed by the bomb, which didn’t explode until bouncing off sandbags about five feet above his head.

His luck eventually ran out, though. On July 21, 1916, the 31st Alberta Battalion rotated back to the Ypres front. Ironically, it was quiet that day, Owen wrote. No gas, no artillery, but there were snipers around. “Deane was the only fatality that day.”

His effects were sent to his mother, then passed from generation to generation. The 1916 diary, the one found at the sa���ʴ�ý sale, will go back to his family, where it belongs.

•••

• Two more quick notes from the book sale:

The May 5 column that mentioned Douglass’s diary also referred to another mystery item, a church psalter written in Cree. It has gone to the Victoria Native Friendship Centre for use in language studies.

Also, Heather Keel wrote in with a shot-in-the-dark plea for another lost item, a cherished baby photo forgotten inside a donated book three years ago. If you have it, please email her at [email protected].

Family treasures matter.

>>> To comment on this article, write a letter to the editor: [email protected]