HALIFAX ŌĆö An engineering study calling for higher dikes to safeguard the land link between Nova Scotia and New Brunswick should have also suggested creating natural buffers to absorb rising oceans, some experts say.

A study released last Friday recommended three options to prevent storms and sea level rise from sweeping over the Chignecto Isthmus ŌĆö all calling for dikes to be raised two metres in work expected to take 10 years.

There would also be a major "water structure" across the tidal Tantramar River ŌĆö essentially a barrier with huge sluice gates to control the incoming tidal waters.

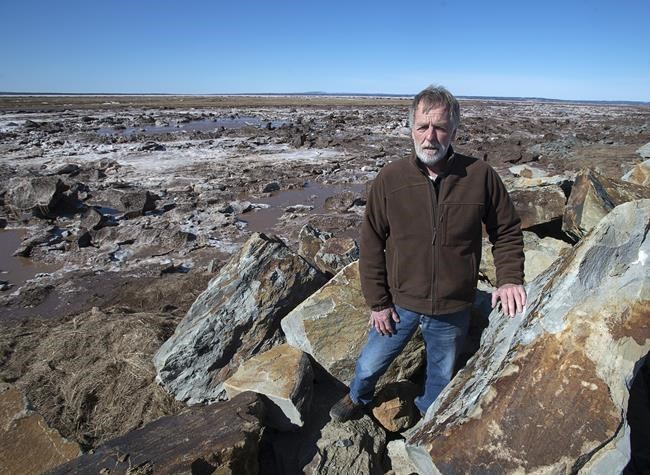

However, Jeff Ollerhead, a professor who teaches coastal geography at Mount Allison University in Sackville, N.B. ŌĆö a town that is vulnerable to climate-related flooding ŌĆö said the study didn't seriously consider having dikes set further inland and reviving salt marshes as part of the solution.

He argues using restored marshland in the lowlands could store carbon, absorb the might of the tides and possibly save money because of lower maintenance costs ŌĆö even if it meant paying farmers to give up agricultural land.

"This report essentially makes no mention of what would be called nature-based solutions or any sort of solution other than conventional engineering solutions," Ollerhead said in an interview Monday.

Ollerhead is also concerned that all options envision the sluice gate system across the Tantramar River. This would replace the river's existing tidal control system located where it runs under the Trans-sa╣·╝╩┤½├Į Highway.

The scientist says the proposed structure reminds him of the causeway built across the Petitcodiac River at Moncton, N.B., in the 1960s, which was replaced last year by a bridge after decades of criticism because of the damage caused to ecosystems.

Ollerhead said the study could have instead considered shifting dikes further inland towards the highway, purchasing agricultural land along the river that would revert to salt marshes and improving the existing tide control system.

Danika van Proosdij, a geographer who leads a Saint Mary's University team that studies natural buffers, said in an interview on Monday she was also concerned to see the study hasn't proposed a clear plan to enhance marshes.

She said one of the study's maps depicts a portion of a proposed new dike that would be moved inland from its existing location, without accompanying commentary on how a marsh might then form in front of it. She says it's an example of how the study hasn't carefully considered the optimal size and conditions for new marshland.

"The risk is if you realign the dike back ... without creating appropriate space and sediment supply for the marsh to re-establish, you're just going to make your erosion problem worse," she said.┬Ā

Mike Pauley, an official with the New Brunswick Department of Transport, said the engineering consultants considered including natural buffers but concluded they wouldn't provide sufficient protection and would require the purchase of farmland.

"We need to understand that people have livelihoods in the lowlands, and there are significant agricultural enterprises taking place. If you did (natural buffering) it would put those folks at a disadvantage," he said in an interview Monday.

Doug Bacon, a farmer in Upper Nappan, N.S., said farmland shouldn't be shifted back to marshes at a time when food security is essential.

"I think the solution is in the dike itself. Agricultural land is of great value and ... the ability to generate food in our own province is one of the most important things we have to look at," he said in an interview Tuesday.

Pauley defended the sluice gate structure across the Tantramar, saying it will only be closed "if there's an extremely large tide coming," allowing fish to pass normally at most times.

Under the study's three proposals, the original network of 35 kilometres of dikes weaving along the shore and the tidal rivers would be shortened due to the new sluice gate structure and proposed realignment of the dikes.

One proposal, priced at $200-million, would see the height of existing dikes east and west of the river raised, with some new sections to be rebuilt. This would create a 17-kilometre system that would cost $7.3 million a year for the provinces to maintain.

The second, $189-million option envisions building a straighter 13.4-kilometre dike in front of the existing one, with annual maintenance costs of $6.9 million. The last, $301-million option foresees raising about 27 kilometres of existing dikes, adding a steel sheet wall, with annual maintenance costs of $11 million.

In an interview on Monday, federal Infrastructure Minister Dominic LeBlanc said Ottawa will likely pay at least half the capital cost for the project the provinces choose.

However, he noted there is also a federal fund dedicated to the use of natural methods. "I would find it personally exciting if a component of this project fit into the natural infrastructure fund of my department," he said.

This report by The Canadian Press was first published March 23, 2022.

Michael Tutton, The Canadian Press