There is much discussion about the implications of artificial intelligence (AI) for humanity.

Many of its impacts are likely to be good — AI has already helped develop new and better antibiotics — but not all of them, and some may be downright ugly.

Moreover, the impact of AI will be magnified and accelerated by developments in the field of quantum computing, which is vastly more powerful than digital computing.

For example, in an April 23 article in The Spectator, Sam Leith notes: “in 2019 Google reported that its 53-qubit Sycamore computer could solve in 200 seconds a mathematical problem that would take the fastest digital computer 10,000 years to finish,” adding that IBM “hopes to have a 4,000-qubit version working by 2025.”

Leith’s article is largely an interview with Michio Kaku, a professor of theoretical physics and author of the new book Quantum Supremacy.

Kaku’s book, writes Leith, argues that the “shift from the digital to the quantum age will be a greater leap than the original digital revolution,” with implications for everything, including the economy, medicine and warfare.

Kaku’s vision of the implications of all this are largely positive, Leith notes. “There doesn’t seem to be a human problem that quantum computers won’t be able to fix.”

These are the good aspects of AI and quantum computing.

But Kaku also sees some of the bad news, noting in particular that all encryption will be able to be broken. So, writes Leith, “potentially, goodbye to all military and civilian secrets, not to mention the secure transactions on which the entire global financial system depends.”

Other bad aspects of the AI revolution include the ability to develop better weapons, better surveillance, better disinformation (including “deep fakes”) and so on.

But these negative impacts, significant though they are, pale into insignificance compared to the ugly potential that AIs could become an existential threat to humanity.

That possibility was imagined as long ago as 1954 in a very short story by a French science fiction writer, Fredric Brown.

In the story, all the computers in the universe have been linked, creating one vast computer. The chief scientist makes the final connection, and then asks the first (and as it turns out, his last) question: “Is there a God?” Back comes the reply: “Yes, now there is a God.”

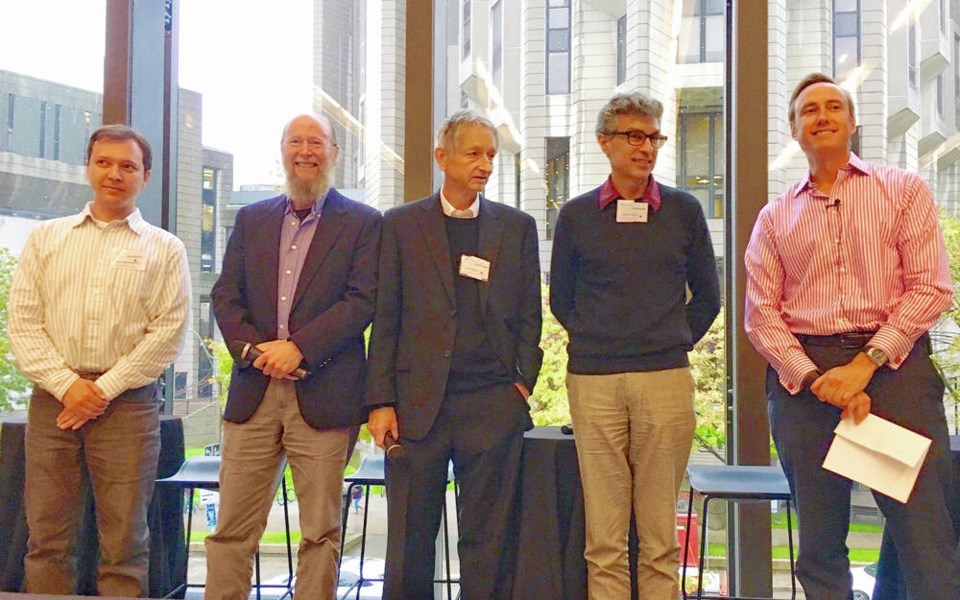

That may sound a bit over the top, but not if you listen to Geoffrey Hinton, known as the “godfather of AI.”

The 75-year-old University of Toronto professor and Google researcher recently retired so he could speak openly about his concerns.

In an interview in the May 23 issue of The Spectator, he noted that the next step — Artificial General Intelligence, or AGI — will mean that in a few years, these AGIs will be smarter than us.

Moreover, he notes, when one AGI learns something, they all learn it, and they will be able to reproduce and evolve, and in essence, never die.

In the past year or so, he says, “I arrived at the conclusion — this might just be a better form of intelligence. If it is, it’ll replace us.”

Of course, we could and should be protected by the Laws of Robotics, first developed by the science fiction writer Isaac Asimov in the 1940s.

The First Law is “A robot may not injure a human being or, through inaction, allow a human being to come to harm,” while the Second Law says: “A robot must obey the orders given it by human beings except where such orders would conflict with the First Law.”

Asimov later added what he called a Zeroth Law, which supercedes the other laws: “A robot may not harm humanity, or, by inaction, allow humanity to come to harm.”

Of course, that means a robot may harm a human if it protects humanity as a whole. It probably also means that an AGI would not allow us to harm the planet’s natural systems by, for example, causing global warming.

So at some point expect the AIs to create the Laws of Humanics, governing our reciprocal responsibility to them.

Will AI be good, bad or ugly? For now that is up to us to, but we should not take too long to decide!

Dr. Trevor Hancock is a retired professor and senior scholar at the University of Victoria’s School of Public Health and Social Policy

>>> To comment on this article, write a letter to the editor: [email protected]