Bullish predictions for the copper market .

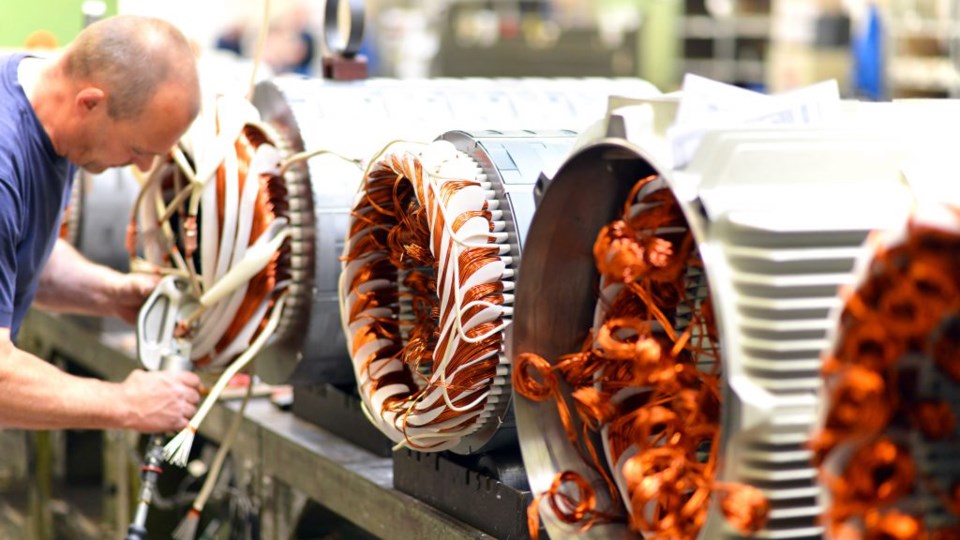

And with robust prices and redhot demand over the past few years, copper mining companies have been .

The only thing missing from this scenario is, well, more copper.

There are few major discoveries and even fewer new mines being built – and at existing ones.

Worries over supply shortfalls are occupying governments and boards and with the average lead time for a new copper mine well over a decade, copper users are seeking nearer term solutions to avoid a supply crunch.

A new examines the scope of copper demand destruction through thrifting and substitution, an issue that “has become a common thread in discussion” in the industry.

And the numbers in the investment bank’s Coping Strategies for Copper Constraint by analysts Rory Townsend and Colin Hamilton are indeed eye-popping.

BMO says in the absence of any further substitution or thrifting, copper semis demand could reach 40.4 million tonnes per year by 2030. Its prediction of maximum demand is up from 31.8 million tonnes last year, or a 2022–2030 compound growth rate of 3%.

But the say authors there is scope – and already instituted programs by original equipment manufacturers – to use less or substitute copper entirely including in electricity transmission and distribution networks, renewable generation capacity, communication cables, industrial air conditioning units, and the transport sector.

Fear substitution

Through this process, the investment bank’s base case scenario sees the potential of just under 10 million tonnes of cumulative copper semis demand eliminated through 2030:

“Our base case remains that substitution and thrifting occurs in a steady, incremental way that is good for prevailing commodity prices.

“However, there is a growing risk that consumers are starting to design around potential constraints before they arise, particularly in the automotive sector.

“Such ‘fear substitution’ would be a challenge to the longer-term demand thematic and would have the potential to significantly hurt both industry volumes and prices.”

If the base case expects the market to chug along nicely, under this “fear” scenario of aggressive substitution, BMO expects an additional 11.6 million tonnes of demand is under risk.

That’s 21.5 million cumulative tonnes at risk through to the end of the decade, or put another way, annual demand of 35.2 million tonnes in 2030 (vs the 40.4 million tonnes) or a CAGR of 1.2% (vs 3%).

Al is your pal

Copper is four times as expensive as aluminium right now – a level up from near 1:1 in 2000 and cheap enough to see the metal replacing copper on a consistent basis, says BMO. While aluminium only has around 60% of the conductivity of copper, in many instances its lower weight could make substitution more compelling over and above cost considerations.

Areas that may see thrifting are the greater use of high voltage direct current (HVDC) power lines that reduce metal intensity in transmission networks, the continuing move to fibre optic communications networks, and renewable generation projects, which are are often small enough to be connected directly to the distribution network and utilise lower voltage cabling which also typically requires less metal per kilometre compared to higher voltage cables, according to BMO.

BMO forecasts the combined length of the global electricy transmission and distribution network to reach 110 million kilometres (68m mi) by 2030.

The investment bank sees air conditioning systems as an area most exposed, particularly in industrial applications where substitution is technically viable. The authors point to aircon giant Daikin, which has a target to halve its global copper consumption by the end of next year.

Down to the wires

EVs use substantially more copper than gasoline and diesel-powered cars, but auto and battery makers are hard at work reducing this.

Thinner copper foil is being used in battery cells, the switch to 800V platforms is facilitating the use of thinner cables, the increased penetration of lower specification vehicles as we progress toward mass adoption, combined with the rightsizing of battery packs and electric motors, should all result in a reduction in copper intensity, says BMO.

BMO says the world ex-China averages 69kg of copper per light duty battery electric vehicle and BEVs in China average closer to 50kg, but “any projections that still include the fabled 80kg need to be adjusted.”

Tesla in May said that starting with the Cybertruck, which is in early production, the Optimus robot, and all future electric vehicles, , compared to the 12V system used in most cars.

In traditional 12V systems, wiring and components must be larger and heavier to handle high electrical loads. With a 48V system, Tesla expects a reduction in battery weight and cost savings.

“First approximation, that means we need only about a quarter as much copper in the car as would be needed for a 12V battery, so that’s a big deal because people often worry about whether there is enough copper,” Musk said.

“Yes, there is.”

Still bullish

BMO takes pains to say “it still believes in the long-term copper thesis and would argue we are still bullish the commodity over the medium term to long term.”

Even under its minimum demand/maximum substitution scenario, the copper market will enjoy positive growth including in non-energy transition related areas like construction, and that is after taking into account the all-important Chinese construction sector:

“Naturally, the future of Chinese property demand is often front of mind when it comes to areas at risk of potential structural decline.

“That said, the focus of stimulus measures and developer focus will likely remain centred on housing completions and shanty town refurbishment, as opposed to new starts, which are typically more copper and aluminium intensive.”