Declining returns of sockeye, chinook and coho salmon in saπ˙º ¥´√Ω have been well-documented, resulting in commissions of inquiry, commercial fishing closures and more than $600 million in federal funding for a Pacific salmon recovery strategy.

Less attention has been paid to a decline of chum salmon on saπ˙º ¥´√Ω’s central coast – a decline First Nations there have been trying to call attention to for some time now.

A new published in Canadian Journal of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences by researchers at the Wild Salmon Center in Oregon confirms central coast chum salmon have declined, on average, by 90 per cent between 1960 and 2020.

For some runs, the declines have been as high as 98.5 per cent, according to the study.

“The declines are shocking,” said Dick Beamish, a Fisheries and Oceans saπ˙º ¥´√Ω scientist who, though officially retired, continues to do research and has organized recent North Pacific Ocean winter surveys aimed at learning more about what is happening to salmon in the open ocean.

“I know that what they’re reporting is reliable because I have been trying to get people to be concerned about chum salmon for a number of years now, particularly in the central coast.

“Personally, I haven’t been able to get anybody in DFO to be interested in it. So all of a sudden, out of the blue, we find this paper. I believe the data are correct.”

Less attention may have been paid to chum, perhaps, because it appeals less to North American palates than other species, like sockeye, which has been a mainstay of the commercial salmon fishery in saπ˙º ¥´√Ω But chum are also important part of the commercial fishery in saπ˙º ¥´√Ω, Beamish said.

“Chum salmon historically are the largest catch of salmon in British Columbia commercially, if you use weight."

He points to historical commercial catch data for saπ˙º ¥´√Ω that shows what he characterizes as a “collapse” that is as bad - albeit less abrupt -- as the collpase of the commercial cod fishery in Newfoundland in the early 1990s.

“We’ve had a colossal collapse of the commercial salmon fishery in British Columbia without a word by anybody,” Beamish said. “It’s as serious as the cod collapse on the east coast.”

Will Atlas, lead author of the study on central coast chum, said he had worked with First Nations on the central coast for several years, including as a PhD student, before joining the Wild Salmon Center, so he was aware of the concerns they had about declining chum returns.

“First Nations People have observed and documented these declines firsthand, but often their local and traditional knowledge has not been valued at management tables,” the paper states.

“Sometimes there is simply a need to quantify the pattern that is being described by people on the ground to help fish managers and policy makers understand the magnitude of changes that are being described by local and Indigenous knowledge holders.”

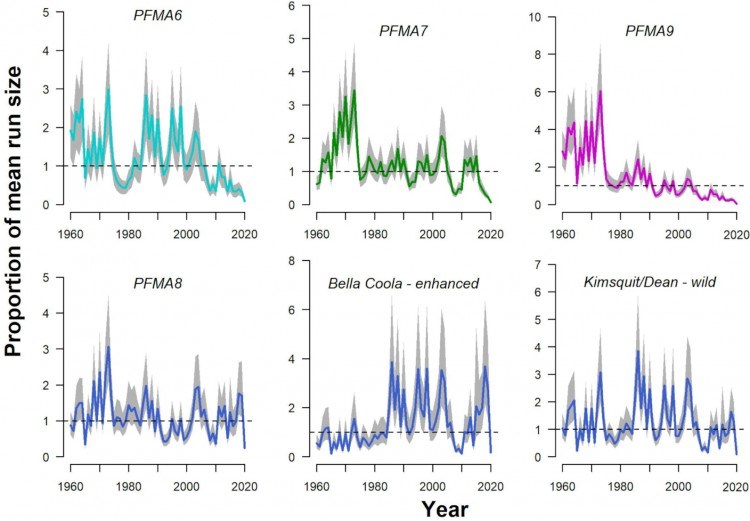

The researchers compiled a time series of chum salmon escapement data for 25 populations from Pacific Fishery Management Areas (PFMA) six through nine. They also looked at commercial catch data.

“These populations were selected because of their relatively continuous monitoring -- at least 50 annual counts since 1960,” the paper notes.

“Our analysis is unique in that we also evaluated individual populations rather than regional stock-aggregate trends, and quantified trends in abundance in the aftermath of a major climate perturbation in the Northeastern Pacific triggering an apparent ecological regime shift impacting salmon survival.

“Our findings reveal major declines in the abundance of chum salmon returning to the Central Coast of British Columbia since 1960, with an average decline of >90% by 2020 across 25 populations with reliable long-term spawner escapement data over the last six decades,” the study concludes.

The paper points to changing marine conditions -- likely climate change driven -- and inter-species competition as contributing factors to the decline.

“Since 2014, the North Pacific has experienced a period of anomalously warm temperatures leading to cascading changes in pelagic (open ocean) and near-shore food webs.”

The study notes that Pacific salmon abundance globally is not declining, but in fact growing. But it’s only growing in the colder, northern ranges, like Russia and Alaska, while southern ranges of Japan, saπ˙º ¥´√Ω, Washington and Oregon have experienced long-term declines of several salmon species. (See BIV on global salmon abundance.)

“These changing marine conditions affecting chum have also corresponded with a period of high overall salmon abundance in the North Pacific, with increasing evidence that interspecific competition for food may be interacting with climate-driven changes to depress growth and survival.”

The study bolsters Beamish’s suspicions that the major cause of mortality in Pacific salmon from southern ranges like saπ˙º ¥´√Ω is poor ocean survival, which he believes is the result of saπ˙º ¥´√Ω salmon not getting enough food in the first few weeks after they leave fresh water.

In other words, it is poor conditions in the near-shore food web in some years that could be the primary cause of poor recruitment, ultimately leading to high mortalities later when chum move to the open ocean, where they spend three or four years competing for food.

Chum salmon may be particularly vulnerable to poor near-shore conditions because they are so small and young when they enter the ocean. Unlike sockeye or coho, which spend a year or more maturing in lakes and rivers before entering the ocean, pink and chum salmon enter the ocean soon after hatching.

While pink salmon live only two years, and spend only 18 months in the open ocean, chum generally spend about four years in the open ocean.

Shorter lived pink salmon appear to be winning the climate change adaptation race, as their numbers remain generally strong even in years when other species decline.

After leaving fresh water, both pink and chum salmon spend their first few weeks feeding in coastal waters before heading into the open ocean. Beamish believes that the key to survival in the ocean has a lot to do with how fast and big they can grow in the first few weeks in coastal waters.

“There are more salmon in the Pacific Ocean today than in recorded history,” Beamish said. “But the changes in the ocean are benefitting the salmon that enter the ocean at the northern parts of the distribution. The issue almost certainly is that the changing ocean habitats are diminishing the capacity at the southern limits of the distribution, and increasing the capacity at the northern limits.”

The Wild Salmon Center study notes that the use of hatcheries to augment salmon needs to be considered -- or reconsidered -- as part of fisheries management.

“While hatchery production has buffered the Bella Coola summer chum population from variable freshwater conditions, several concerns remain for the long-term health of both the Bella Coola summer chum stock, specifically, and Central Coast chum more generally.

“Despite large-scale enhancement and static production goal of 7 million fry, Bella Coola chum salmon run sizes have still fluctuated 29-fold in the last decade.”

The study suggests reduced hatchery production could actually benefit wild chum and other species “which compete with enhanced chum salmon for limited resources in the nearshore environment.”

Chum on the central coast have supported a large gillnet and seine fishery in the past, Atlas said. Their numbers have been augmented with hatchery production, with Bella Coola hatchery chum accounting for 50 per cent of central coast chum abundance. But despite hatchery enhancements, Bella Coola chum have experienced “wildly variable returns,” Atlas said.

“In a lot of instances, when hatcheries become the predominant source of salmon production in a watershed, you can get this run-away domestication, or artificial selection regimes, that start to alter the underlying traits that really shape survival,” Atlas told BIV News.

“They release all those fish from the hatcheries into the river environment within two days of each other – seven million. So they’re all going to sea at once. If it’s good conditions that they encounter in the ocean when those fish hit the ocean, then they might have a great return. If it’s bad conditions they encounter in the ocean, they may have a terrible return.

“We’re seeing really similar things in the Sacramento River basin, where fall chinook are really dominated by hatchery production. If you dump the fish on the right day, they do great. And if you don’t, they have very little return.”

Chum, like some other salmon species, appear not to be adapting to changing ocean conditions – like warmer water – the way pink salmon have.

“They (pink salmon) can grow well at a variety of temperatures, they grow extremely rapidly, they have a two-year life cycle -- so they can bounce back from disturbances quickly -- and they can have extremely high productivity as a species in terms of replacing themselves and rebuilding,” Atlas said.

“Chum have a longer life cycle, they are more cold water adapted, we think, in the ocean. So yes, early marine survival probably matters for chum. Probably competition with enhanced (hatchery) chum in the near-shore environment may well be depressing the survival of other species on the central coast.”

DFO implemented comercial fishing closures in 2021, as a result of recent poor returns, which Atlas said was appropriate. He thinks the commercial fishery can survive in B.C, but not at its current scale. He suggests the commercial fishery needs to be right-sized to declining stocks.

“It doesn’t necessarily look bad for fisheries that are scaled appropriately to the abundance of the resource,” Atlas said.

One thing salmon on the central coast have going for them is relatively healthy, intact watersheds.

“I think the central coast is a place where we can have optimism about salmon, but we also need to realize the days of having multiple openings a week, where 200 or 150 gillnet boats are out, that’s probably over.”

To address the crisis of saπ˙º ¥´√Ω’s declining salmon stocks, the First Nations Fisheries Council of BC is launching a new First Nations-led initiative to address the crisis. The initiative will be discussed at a public event Monday in Vancouver.