Vancouver-headquartered Ivanhoe Mines (TSX:IVN) is among the global mining companies being criticized by Amnesty International for alleged human rights violations in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC).

The alleged violations include the relocation of villagers for new mines and mine expansions and the sub-standard housing they were provided with as part of the relocations.

Some of the relocations in question were forced evictions, though that was not the case for the Ivanhoe Mines project – the Kakula copper mine – an Amnesty International researcher confirmed. In that case, there was an agreement in place with villagers relocated to make way for the new mine.

But ultimately, Amnesty International says Ivanhoe Mines fell short in providing basic services like electricity, running water and a sewage system as part of the relocation.

The DRC is where much of the world’s cobalt is mined. It is also a significant producer of copper. Both metals are critical to electric vehicle batteries, and the Amnesty International report suggests the mining of critical minerals needed to solve the climate crisis is creating a humanitarian crisis in the DRC.

“In the rush to build a green economy, Canadian companies must not trample over the lives and livelihoods of anyone they perceive to stand in their way,” Ketty Nivyabandi, secretary general for Amnesty International sa国际传媒, said in a press release. “We must ensure that affected communities have access to accountability and justice when their rights are under threat.”

A by Amnesty International and the Initiative pour la Bonne Gouvernance et les Droits Humains (IBGDH) focuses on four mines in the DRC, including the Kakula copper mine, developed by the Kamoa Copper mining company.

Ivanhoe owns 39.6 per cent of the Kamoa Copper Company. China’s Zijin Mining owns 39.6 per cent, and 20 per cent is owned by the DRC government.

In 2018, to facilitate the Kakula mine’s development, the company negotiated the relocation of 45 households. The householders that were relocated were given new houses, title deeds and US$250, according to an appendix to the Amnesty report.

Three of the four cases Amnesty looked into were forced evictions, but the Kamoa-Kakula mine was not one of them.

“We’ve conceded that Kamoa has not displaced people against their will,” Candy Ofime, an Amnesty International researcher and report co-author, told BIV News. “What we’re saying, though, is that the resettlement options they’re offering are inadequate.”

For the report, Amnesty and the IBGDH conducted two group interviews with 10 people in the town of Muvunda, where the resettled households were relocated.

“Resettled individuals told Amnesty International and IBGDH that Kamoa provided them accessible information about the development of the Kakula Mine, meaningfully assessed their demands, and facilitated their resettlement,” the report states.

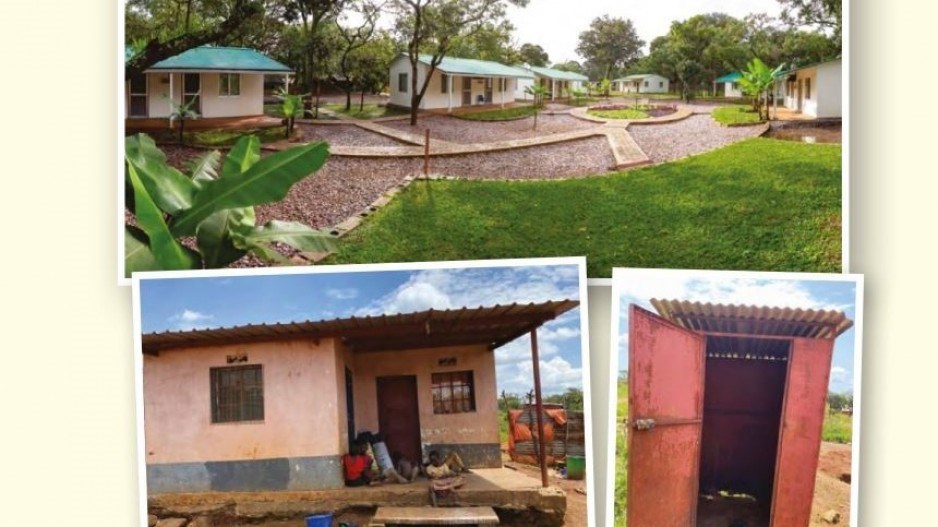

“However, they also said that the resettlement complex Kamoa built departed from the living standards the company agreed to. During their field visit, researchers confirmed that substitute housing and social infrastructure the company built fell short of both Congolese and international human rights standards on, among others, the right to adequate housing.

“Researchers observed that substitute houses Kamoa built in Muvunda are not equipped with running water, electricity, or connected to any sewage system,” the report’s authors wrote. “Many reported that at the time of the eviction, resettlement houses were too small for their family sizes.”

“Kamoa’s parent companies, including Ivanhoe Mines, have a duty to bring the replacement houses in Muvumba up to international standards,” said Nivyabandi.

Ivanhoe declined to respond to the Amnesty report, but pointed to its detailed responses contained in the appendix to the Amnesty report.

There the company notes that the agreement to replace homes were on a “like-for-like” basis, and presumably that means that the homes that were replaced did not have electricity, running water or flush toilets either.

But Ofime notes that the company boasts that its mine is powered by clean hydro-electric power supply, and that the homes the company built for mine workers and contractors all have running water, power and sewage systems.

“Our approach has been to say, irrespective of what people had, if you’re displacing communities for the sake of resettling them, you cannot have a double standard between what you’re offering your staff, what facilities you’re able to build for the process of extracting and processing the minerals you’re mining,” Ofime said.

While the new homes provided by the company may well be as good or better than what the villagers had before relocation, they don’t meet international or Congolese standards, Ofime said.

“Irrespective of whether or not it was agreed upon, we’re saying people should have electricity,” Ofime said. “As an international company that makes millions and millions of dollars each year through the extractive process, that’s the least you can do for the people you are moving within your concession.

“I can assure you that Kamoa staff who live on the concession have toilets that (are) connected to a sewage system, definitely have running water, and for sure have access to electricity."

Other concerns raised in the report was the delay in providing social services, like a new school and health centre. While the households were relocated in 2018, they did not get a new school until 2021 and a new health centre until 2023, Ofime said.