LONDON (AP) ŌĆö South African author Damon Galgut has mixed feelings. This has been a great week for him, a good month for African writers ŌĆö and a terrible year, he says, for his country, blighted by pandemic and corruption.

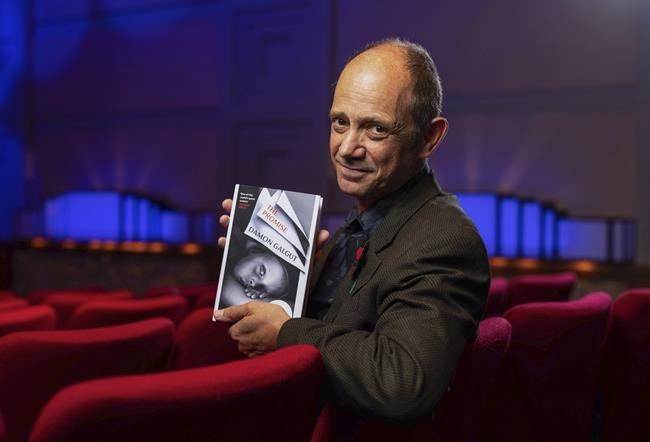

Galgut won the Booker Prize for fiction on Nov. 3 for his novel ŌĆ£The Promise,ŌĆØ the story of a white South African family in decline in the years before and after the end of the racist apartheid system.

Receiving the 50,000 pound ($67,000) award at a ceremony in London, Galgut, 57, said he was accepting it ŌĆ£on behalf of all the stories told and untold, the writers heard and unheardŌĆØ from Africa.

Galgut is pleased that ŌĆ£a long-term resistance in Europe or America to receiving African voicesŌĆØ may finally be easing. Tanzanian novelist Abdulrazak Gurnah was awarded this yearŌĆÖs Nobel Prize for Literature in October. And last week, SenegalŌĆÖs Mohamed Mbougar Sarr became the first writer from sub-Saharan Africa to win FranceŌĆÖs leading literary award, the Prix Goncourt.

But, Galgut added, the issue is ŌĆ£double-edged.ŌĆØ

ŌĆ£Really, the transformation that needs to take place is not only in Western publishing ŌĆö itŌĆÖs also in Africa itself,ŌĆØ Galgut told The Associated Press, citing a dearth of publishers and booksellers. ŌĆ£I would like African governments to start taking their own artists seriously.ŌĆØ

ŌĆ£The PromiseŌĆØ opens in the apartheid-era 1980s, when dying Rachel Swart makes her husband promise to give their Black maid, Salome, her own house. The novel follows family members over several decades, and through a series of deaths, as the promise remains unkept.

Historian Maya Jasanoff, who chaired the Booker judging panel, called it ŌĆ£a book about legacies, those we inherit and those we leave.ŌĆØ

ItŌĆÖs a family story that can also be read as a state-of-the-nation novel, something Galgut says is hard to avoid for a South African writer.

ŌĆ£Maybe more than lots of other countries, South AfricaŌĆÖs recent past is not past yet,ŌĆØ Pretoria-born Galgut said in an online interview from his publisher's office in London. ŌĆ£So even if you wanted to write a story that was not dealing with politics or history, if you create any particular character, you have to take account of the fact that they come from somewhere, they have a background.

ŌĆ£If youŌĆÖre a white person, your history is very likely to be charged in a different way than if youŌĆÖre a Black person. Did you participate in the military as a white person? What are the implications of that? Are you from a monied background, are you from a dispossessed background? All of that was shaped by our recent past, so you sort of have to take it into account.ŌĆØ

ŌĆ£The PromiseŌĆØ is told by a slyly humorous narrator who flits among characters, revealing the inner thoughts of people and even animals. The effect is a rich tapestry of South African voices.

ŌĆ£The notion that any one single voice can speak for South Africa is false,ŌĆØ he said. ŌĆ£WeŌĆÖre a chorus ŌĆö a very dissonant, discordant chorus, but we are a chorus.ŌĆØ

ThereŌĆÖs one exception: Salome, whose thoughts readers never hear. Galgut is aware that could be seen as marginalizing a Black character who should be at the center of the story.

ŌĆ£The vast majority of South AfricaŌĆÖs dispossessed or poor citizens are still the people who were made poor under apartheid, and their position has not changed,ŌĆØ he said. ŌĆ£So it seemed important to me that I convey to the reader the sense of silence that surrounds a character like Salome, and I made the decision, rightly or wrongly, to do that through making her a silent presence.

ŌĆ£I thought I could make the silence speak, actually, but the only way to do that is to make the silence problematic.ŌĆØ

Open to English-language novels from any country, the Booker Prize has a reputation for transforming the lives of its winners, who have included Salman Rushdie, Margaret Atwood, Hilary Mantel and Marlon James. Galgut won the Booker for his ninth novel, and on his third time as a finalist. He was previously shortlisted for ŌĆ£The Good DoctorŌĆØ in 2003 and ŌĆ£In a Strange RoomŌĆØ in 2010.

He is the third South African novelist to win the Booker Prize, after Nadine Gordimer and J.M. Coetzee, who has won twice. Galgut, who lives in Cape Town, is gratified the novel has ŌĆ£hit a nerveŌĆØ in his home country, where its central theme of land and who owns is it ŌĆ£at the center of South African political life.ŌĆØ

But heŌĆÖs despondent about his homeland, which he says is in ŌĆ£a state of moral exhaustionŌĆØ amid a pandemic that has killed almost 90,000 South Africans and battered the economy.

ŌĆ£South AfricaŌĆÖs economy was in a pretty bad state before COVID hit, but itŌĆÖs really dire now,ŌĆØ he said.

Hundreds of millions of dollars in public money earmarked to fight the COVID-19 pandemic in South Africa has been misappropriated by officials, according to investigators -- just the latest example of the corruption afflicting AfricaŌĆÖs most developed economy.

ŌĆ£ThereŌĆÖs a general sense of dejection and aimlessness, which is kind of new,ŌĆØ Galgut said. ŌĆ£South Africans are fairly resilient and very given to the hope that we can change things, we can transform things. But that hope is in short supply right now.ŌĆØ

Despite the gloom, Galgut is driven to explore the world around him. HeŌĆÖs mulling the idea of writing about the pandemic and the ŌĆ£strange existential chambersŌĆØ created by lockdowns.

But he says heŌĆÖs too cynical to believe that his book, or any book, can change the world.

ŌĆ£On the other hand, what I do believe is that books cumulatively change human perception," he said. "So thereŌĆÖs a very big difference between people who read novels and people who donŌĆÖt. Donald Trump, for me, is a man who doesnŌĆÖt read novels, Jacob Zuma is a man who doesnŌĆÖt read novels. Barack Obama strikes me as someone who does. Why? ItŌĆÖs because I think the function of novels is to make it clear to you that the world is not made in your own image.

ŌĆ£So in that sense, books matter.ŌĆØ

Jill Lawless, The Associated Press