PREVIEW

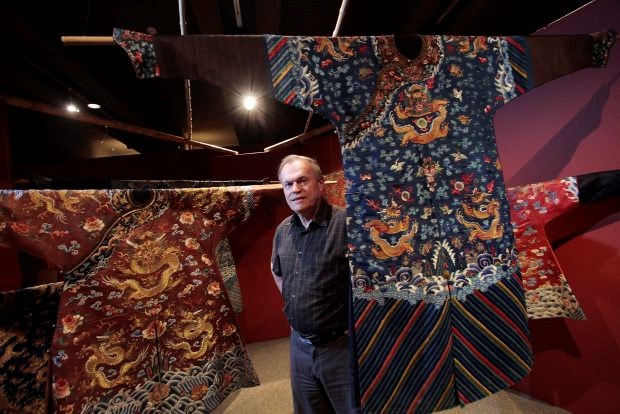

Silk Splendour: Textiles of Late Imperial China (1644-1911)

Where: The Art Gallery of Greater Victoria

When: Friday through Sept. 23

Tickets: Regular gallery admission ($13 adult, $11 seniors/students, $2.50 youth, $28 family, free for members and children).

Intricately embroidered silk robes and handcrafted wall hangings may be beautiful to look at, but each piece in the Art Gallery of Greater Victoria's latest exhibit also tells a story about history and culture.

The tiny foot bindings are a reminder of a time when cracked arches were a sign of attractiveness and wealth, according to Barry Till, curator of Asian art.

The fitted cut of robes was less about flattering one's figure than practicality and cultural domination. It was more appropriate for riding horses - and when the nomadic Manchus took power, their dress code trickled down.

There are also individual stories - for example, the eight-by-four-foot wall hanging with a peacock feather woven into it that would have taken years of labour.

Its owner was once offered a horse and carriage in exchange for the work of art, as the story goes, and refused.

Another informal robe was worn by the last empress, famously played by Joan Chen in The Last Emperor.

Silk Splendours opens Friday and presents silk creations from the Qing Dynasty, the last Chinese empire before the republic's creation in 1911. About 40 robes and 10 skirts are displayed alongside panels, hats, shoes, jewelry and more.

Though the show focuses on the Qing Dynasty, silk in China has a long and storied history, Till says.

"The Chinese are synonymous with silk," he said.

"They kept its production a secret for literally millennia."

After the silk-making process was developed about 3000 BCE, he said, a few discreet smugglers brought it to the West. One Chinese princess snuck some silkworms along when she married the King of Khotan, an area now part of China, in the fifth century.

In the sixth century, it was Christian monks who carried the worms to Constantinople.

The world's enchantment with silk also has its racy side, at least in the case of the Romans ("It was perfect for their orgies, apparently, because it would drape a person nicely").

Silk Splendour was made possible through two major donations to the gallery, which has the second largest collection of Asian art in sa国际传媒 after the Royal Ontario Museum. The first came from two American collectors, Fyle Edberg and Paul Foote, by way of their estate manager. The second came from the Menzies family of Ontario, whose donation was the impetus for the exhibition. Rev. James Menzies was a Christian missionary in China during the 1920s and 1930s. His son Arthur was the Canadian ambassador to China in the 1970s.

The exhibition is accompanied by an illustrated exhibition catalogue featuring an essay by Till.