When Adam Ravetch accepted Oscar-nominated filmmaker Greg MacGillivray's invitation to journey to the North Pole in 2008 to work on To The Arctic, it was a homecoming of sorts for the Victoria-based cinematographer.

Ravetch and his wife, photographer and filmmaker Sarah Robertson, have documented the migration of walruses and polar bears in the Far North for 15 years. This was the first time Ravetch worked there with Imax cameras, however.

"I've been focused on the Arctic for so long," said the filmmaker, who is featured in the 40-minute movie, which opens today at Imax Victoria.

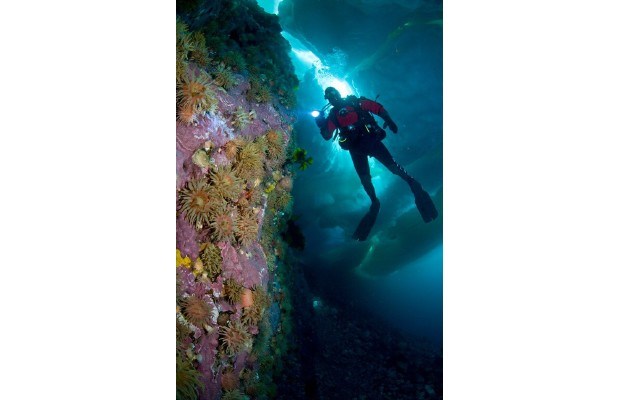

He provides input and is seen scuba-diving with polar bears under huge ice holes and around a stunning coral reef.

From the breathtaking aerial shot of a massive, melting ice shelf that opens MacGillivray's wildlife stunner to striking footage of Arctic creatures doing what comes naturally, To the Arctic weaves cautionary messages about climate change into a crowdpleasing portrait of a mother polar bear and her twin cubs.

Their struggle to adapt to thinning ice floes and other challenges in the ever-changing Arctic wilderness is intercut with passages on caribou migration, the plight of the walrus and the indomitable spirit of Inuit inhabitants.

Between its remarkable 70mm cinematography and undersea footage, peppy Paul McCartney soundtrack, cool visual effects and Meryl Streep's soothing narration, MacGillivray's family-friendly film is as watchable as such Imax eco-spectacles get.

Ravetch and Robertson, who produced his segments, operate Arctic Bear Productions from their Cadboro Bay home.

Highlights include Polar Bears: A Summer Odyssey, their recent wildlife documentary charting a threeyear-old polar bear's migration through Hudson Bay before spending his first summer alone on land, and Arctic Tale, their 2007 docudrama for National Geographic Films and Paramount Classics contrasting the struggles of a female polar bear cub and walrus pup.

"It's kind of neat being up on the big screen," says the southern Californiaraised scuba diver, who got into filmmaking after earning a degree in marine biology at San Diego State University and leading expeditions as a guide and dive master.

He admits it might sound strange for someone with such a beach background to end up in such a frigid place.

"I keep trying to get out of the Arctic but they keep pulling me back in," he jokes.

"It was the furthest thing from my mind until I met John Stoneman [the British naturalist who produced and hosted CTV's The Last Frontier from 1987-1990]."

Ravetch was hooked when Stoneman took him to the Magdalen Islands, where he first went diving with harp seals.

"There weren't many people documenting the Arctic then and I was looking for a place with room for photographic discovery," he recalled.

"It was foreign to me, alien-like being under the ice with walruses and unicorn whales."

For To the Arctic, Ravetch collaborated with Victoria diver and undersea photographer Dale Sanders.

"We needed well-trained cold-water divers who could endure underwater conditions for long periods of time," said Ravetch, noting they went to the Arctic early to cut and prep ice holes for their stay from May to August.

"It was great getting the bears swimming underwater, showing the glory of this mammal in its water realm," said Ravetch, who often dove with cinematographer Bob Cranston.

W hile polar bears are camera-shy, the filmmakers lucked out when they encountered their furry "stars," who provided a close-range window into their lives.

"If polar bears don't want to be around you, they'll take off," Ravetch said.

"We'd just let them go. It's not worth it to disturb them."

Is diving with polar bears and walruses as potentially hazardous to your health as it seems?

Ravetch says experience helps, and you have to be on guard.

"There's also this huge camera between you and the animal that makes you feel more comfortable," he said with a laugh.

He said it's the walruses he's more concerned about.

"We were in the belly of the herd," Ravetch said, recalling a sequence in which they were in front of several "protective and potentially very dangerous" female walruses swimming with their babies.

A mother suddenly swam toward them but just nudged the camera.

"That's what I love about the Arctic," he said.

"You think it's this harsh and difficult place but it reveals a vulnerable and sensitive side, like a walrus kissing a camera."

While shooting a wildlife documentary can be like "guerilla warfare," Ravetch said Imax is a different beast.

"You have to be ready for anything, be mobile and go with the weather and what the animals are doing."

With the bulky Imax cameras, "you can't just run over and shoot" whales you might spot mating 200 yards away, he said.

Other logistical realities included having to use a crane on a boat to lower the cumbersome camera into the water before getting ahead of the bears they were about to shoot using a cartridge with only three minutes of film.

"You have to make the choice when to pull that trigger," said Ravetch, who also got to reunite with another subject - Simon Qamaniq, a colourful Inuit seal hunter, accordionist and master sculptor he befriended on Baffin Island in the mid-1990s.

Ravetch said the Inuit are "definitely" affected by the climate-change effects he's witnessed.

"There are areas where the glaciers are smaller, where the ice breakup has changed, and guess what that means for polar bears?" he said.

"There are even birds that dive down, and the fish that used to come up are no longer available."